Only point of Indigenous voice to parliament contention is constitutional enshrinement, the rest is noise

Liberals are divided on this issue like never before. As the referendum looms closer, emotion on both sides has turned to vicious abuse. Many messages I receive challenging my support for the voice are aggressive.

Many messages I receive challenging my support for the voice are aggressive, mostly from strangers but also from people I know. An Indigenous opponent texted me this week saying they were going to “f..k you Noel c.ck suckers” – referring to Noel Pearson – and asking whether Pearson has photos of me “f..king a dog”.

The ugliness taints both sides. Pearson has rightly been criticised for accusing Jacinta Nampijinpa Price of “punching down on blackfellas” and then last week alluding to Holocaust imagery to attack Julian Leeser.

What is this debate revealing about us? It has long been my assessment that Australia is one of the least racist countries on Earth, but clearly racial tensions, when they emerge, spark a particular volatility.

BEST OF VOICE OPINION:All our commentators weigh in on the Indigenous voice to parliament

Racist abuse still occurs and often rears its head in sport. It happened again this week when a disgusting social media post targeted Adelaide Crows star Izak Rankine referencing his Aboriginality and petrol sniffing.

Here is a young man with the talent, discipline and drive to excel in professional sport, and he endures that sickening abuse. For the victims it cuts to the core, and these moronic acts drag us all down.

Enough is enough, we all say, but that means there is plenty of work left to do. If reconciliation means getting rid of underlying racial tensions, and removing discrimination and disadvantage, then we know we have a long way to go.

This does not mean you must support the voice to support reconciliation – we should be able to respectfully disagree and accept that good intentions can take different paths. Yet it is clear the voice debate will shape the progress of reconciliation for years to come.

Peter Dutton has engaged deeply on the voice. He flirted with support and has not been persuaded by hardliners claiming the voice is racially divisive, but in the end Dutton has chosen to solidify the support of his conservative base by rejecting the voice.

The alternative would have been to embrace or even improve the reform, signalling Liberal commitment to practical reconciliation, taking the hard edges off Dutton’s political persona, and allowing the Opposition to focus on more electorally significant issues such as energy policy and the cost of living.

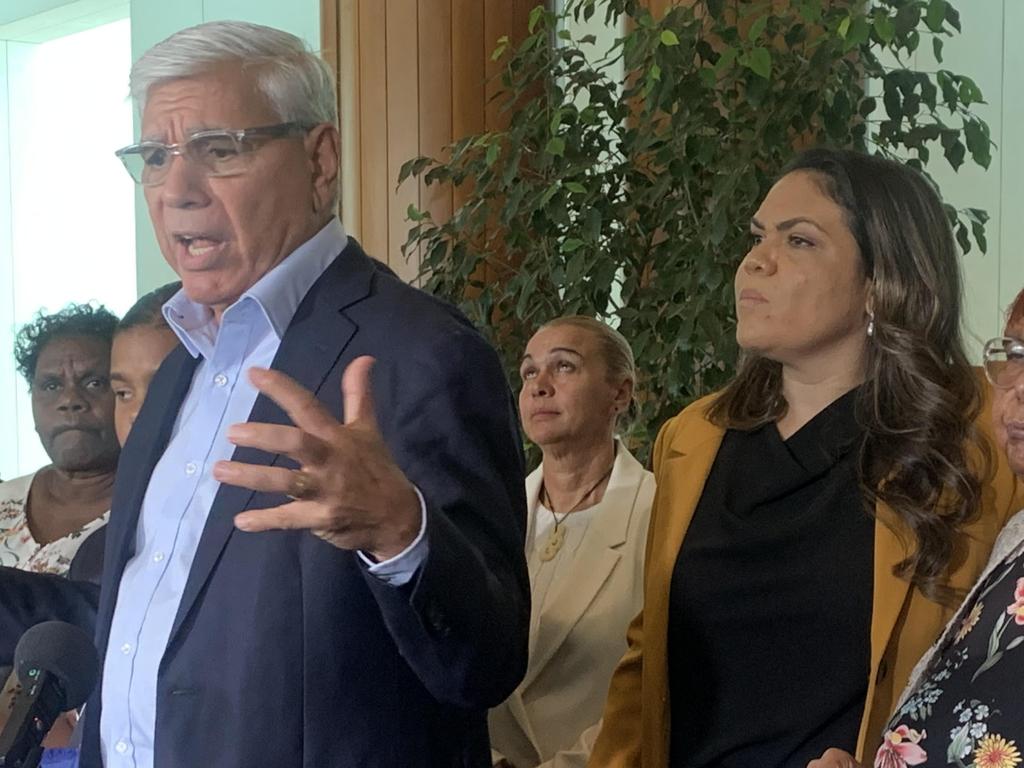

The predicted Liberal fracturing is still unfolding with the high-level defections of the first Indigenous minister for Indigenous affairs, Ken Wyatt, and Dutton’s own shadow minister for Indigenous Australians, Julian Leeser, hurting the Opposition Leader’s stand. The two Liberals with the most intimate experience and expertise on the voice oppose the party’s position.

The Liberals’ Senate leader, Simon Birmingham, declared he would not argue the No case, making his discomfort with the policy clear, prompting one of his own colleagues, Alex Antic, to declare his leader’s position as “untenable”. And consider this: across federal and state parliaments, there could well be more Liberal MPs arguing the Yes case than running Dutton’s No case.

The Liberals are divided on this issue like never before – the only comparable split was over the republic referendum, but that was deliberately left open as a free issue. On the voice, the official party position is being repudiated by senior Liberals.

While the voice proposal will not have official bipartisan support, it already enjoys a high degree of cross-partisan advocacy. The political stakes are elevated, with the result likely to deliver a crushing blow to either the Prime Minister or the Opposition Leader.

Dutton and Nationals leader David Littleproud must find a way to promote Senator Nampijinpa Price, who sits in the Nationals partyroom, into the Indigenous affairs portfolio. She is the most powerful and credible No advocate and provides the only hope for the Coalition to block the voice.

Liberals campaigning for the Yes case must know that if their cause triumphs, Dutton will be skewered. Not that this should be their concern, because both sides say the result is crucial for the nation – No campaigners believe a voice will be disastrous; Yes supporters fear repudiation will derail reconciliation.

As the debate polarises, key flaws in the No case crystallise. Coalition figures from Dutton down have argued an Indigenous voice would be bureaucratic and unworkable – yet they are proposing to legislate a voice of their own.

If the Coalition can legislate an effective and useful voice under existing powers, then clearly so too can any government under a constitutional mandate. As I have pointed out repeatedly, the only point of contention is constitutional enshrinement; the rest is noise.

Opponents rail against altering our Constitution as too risky and warn against racial references, yet they laud the uncontested changes of 1967 that included Indigenous Australians under the federal race power. Coalition opponents feign ignorance over details even though they convened and completed a voice co-design process little more than a year ago (declaration: I was involved).

For all that, Anthony Albanese and his Minister for Indigenous Australians, Linda Burney, have been indolent in their advocacy. Rather than debunk criticism, they ignore the specifics, attack the critics and make emotional appeals. And, while the co-design work has been done, Albanese is yet to detail which aspects his government would legislate.

While the most pertinent detail for the referendum is the constitutional wording, Labor needs to understand that voters deserve the comfort of knowing more about the voice model the government would legislate. To hold back this detail insults voters and, rightly, makes them suspicious.

There is only one logical, big-picture argument against the voice proposal, and it can be readily dismissed. This is the philosophical objection to separating citizens or awarding certain rights according to race; it flows from the liberalist ideal most of us would share, about all citizens being equal under the law and the Constitution being racially blind.

This argument makes the perfect the enemy of the good – it is ideologically pure rather than practical. If we want to deal with the world as it is, rather than as an ideal, we have to acknowledge a pertinent series of facts: Indigenous Australians are disadvantaged (reference the Closing the Gap agenda); Indigenous Australians, under Mabo, native title and cultural heritage laws, hold distinct rights not available to other Australians; race has always been in our Constitution; the 1967 referendum specifically gave the federal government power to make laws and policies for Indigenous Australians; a wide range of polices, programs and agencies across state and federal governments are specific to Indigenous Australians; for all these purposes (in a distinction that some dismiss as semantics but which is intellectually and morally important) Indigenous Australians are not considered so much as a “race” but as a cohort descended from the original inhabitants, and; these laws and policies are not aimed at creating or maintaining inequality, but at overcoming disadvantage to achieve equality.

These facts show why giving Indigenous people a voice to advise on these matters is fair and reasonable, likely to produce better outcomes, and engender a sense of responsibility and accountability. This also demonstrates why comparisons with apartheid are particularly odious – using the smear of a toxic form of racial oppression to attack an attempt to lift Indigenous Australians out of disadvantage.

This is why the “racially blind” argument falls over. In the real world, Indigenous Australians are treated differently under some laws and face unique challenges, and a realistic and fair nation should adopt special measures to overcome this dilemma – this is the essence of reconciliation.

When we have equality, when the gap is closed, perhaps we could have another referendum to scrap the voice because its work will be done. Maybe – but sadly the evidence suggests none of us will live long enough to see that day.

Many No advocates now ask why we do not just offer a symbolic recognition of Indigenous Australians in the Constitution and legislate a voice. This takes the debate back 10 years and fails to grasp central points that should appeal to conservatives.

Words in the preamble that recognise any special place or connection for Indigenous Australians could carry constitutional risk, they could be over-interpreted by the High Court in the future – something that must be of great concern to those No campaigners talking up the risks of the current proposal. More likely, however, these words would be bland and deliver nothing but a small symbolic recognition.

Crucially, the voice proposal has emerged from the debate about recognition. It is a proposal to enact recognition in a way that delivers practical rather than symbolic change – reflecting conservative values.

After long consultation and the rejection of more radical proposals, such as the insertion of a racial non-discrimination clause, the voice won broad Indigenous consensus.

To argue against it is to reject practical change in favour of symbolic change, and to oppose the only form of recognition on offer, requested by a broad consensus of Indigenous Australians.

The visceral nature of some of the opposition to the Indigenous voice to parliament has been surprising. The proposal generates fear and resentment from some, which is confounding given we are usually a practical and generous nation.