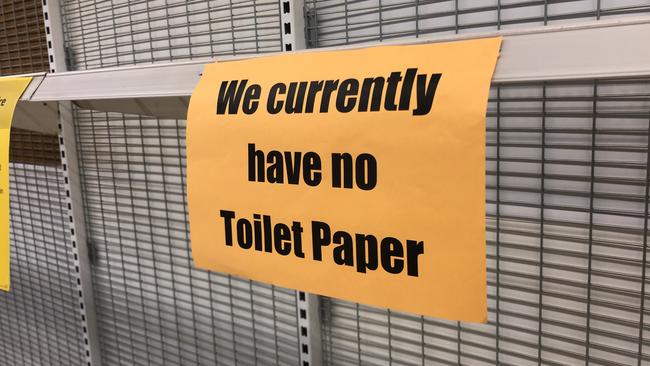

Panic buying of toilet paper in supermarkets as Covid restrictions hit Australia

In the pandemic’s early days, panicked shoppers cleaned out supermarket shelves – then Team Australia came to the rescue.

It’s the “big little luxury”, apparently the nation’s most cherished toilet tissue with “three-ply air quilted softness”. If you believe the retail paper pushers, Quilton “loves your bum”.

When that intimacy is imperilled, Australia can slip into a post-apocalyptic dystopia.

At 7am on a Saturday in early March 2020 at Woolworths Chullora in Sydney’s southwest, there was “action in aisle 10”, as a magistrate would describe the incident at trial. A mother and daughter had loaded a shopping trolley with eight 36-roll jumbo packs of Quilton. A woman grabbed one of the packs, bolted, and then all hell broke loose. Another shopper recorded the altercation on their phone, capturing the screaming and yelling and swinging arms. “It was crazy,” the daughter told police, who would charge the pair with affray. The video of the incident went viral.

Later that day, Bankstown Police Area Command duty officer Acting Inspector Andrew New said there was no need for people to go out and panic buy paracetamol, canned food or toilet paper. “It isn’t the Thunderdome, it isn’t Mad Max, we don’t need to do that,” New told reporters.

In July 2020, Treiza Bebawy, then 61, and her daughter Meriam, 23, were found guilty of affray in the local court and placed on good behaviour bonds; they lodged an appeal in the district court on the grounds of self-defence, which was upheld by the judge, given the third party, Tracey Hinckson, 49, did not give evidence in the case.

The “action in aisle 10” is one of the pandemic’s enduring episodes, a national keepsake of a wild time when panic set in and Australians acted both rationally and irrationally when there was no playbook to guide us; when supply chains could not withstand the surge in demand; when appeals for calm and to stop hoarding from the very top were often ignored; and as months of grinding lockdown and restrictions led to outbreaks of Team Australia ingenuity, adaptability, sacrifice and resilience.

When the World Health Organisation declared the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020, the nation had a case of the runs – panic buying of groceries such as toilet paper, cleaning products, flour, rice and pasta. The value of retail sales doubled in a single month for those products.

“It was surreal for everyone working in the business,” says Belinda Driscoll, managing director of Kimberly-Clark Australia and New Zealand, makers of Kleenex tissues and toilet paper. “We went from business as usual to a moment of crisis and transition.”

In early March, chief medical officer Brendan Murphy said “it’s pretty clear that this disease is going to be with us for a while”, so the focus was to slow any spread. At Senate estimates, when there were 41 confirmed infections and one death, the CMO said there was “no evidence of widespread community transmission”, other than in a few pockets in Sydney.

The health system was well prepared, but there was another worrying outbreak. “We are trying to reassure people that removing all of the lavatory paper from the shelves of supermarkets probably isn’t a proportionate or sensible thing to do at this time,” he said.

That message wasn’t cutting through to shoppers, amid social media posts of buyer frenzies and broadcast images of long queues at supermarkets, empty shelves and rising tensions. The herd was off. Woolworths announced a limit of four packs per customer transaction; Coles and Aldi followed suit with restrictions. “The fear of missing out was going through the roof,” Coles Group chief operations and supply chain officer Matt Swindells recalls.

In early March at a supermarket in Wodonga, on the Victorian side of the border with NSW, Swindells was helping with the night fill. He noticed a customer buying up all the Listerine. “She told me it could stop her getting Covid,” Swindells tells Inquirer. “Then I saw there was one pack left of toilet paper on the shelves and I thought this is going to be a huge issue.”

The problem wasn’t inventory as such, as manufacturers moved into 24/7 production and were producing more volume and faster than ever. Amid the panic buying, Swindells did a live cross on breakfast TV from a distribution centre filled with toilet paper; in an instant he’d found a memorable form of words to cut through the jargon of supply chains and inventory. The issue was akin to the days of the six o’clock swill in pubs.

“To be clear, there is lots and lots of stock in the system,” the two-decade retail veteran told Nine’s Today program. “I described it earlier today to someone as like being in a pub where everyone goes to the bar at once and everyone orders 10 rounds of drinks at the same time. There’s probably beer in the pub but you cannot physically service that demand in one go.”

The Productivity Commission’s Catherine de Fontenay says panic buying happens for the same reason bank runs used to happen. “No bank can survive if most of its customers withdraw at the same time,” the PC commissioner says.

“Nowadays we solve the risk of bank runs through government guarantees, but there is no comparable solution to panic buying,” de Fontenay says, recalling Jimmy Stewart’s speech in Christmas classic It’s a Wonderful Life.

“We need reminders to try and be altruistic, since some people will miss out if there is a shortage.”

Driscoll says production at Kimberly-Clark’s Millicent mill in South Australia was ramped up from 1.8 million cases (of 80 rolls) a month to 2.5 million. The company shifted to nine-pack packaging to get more on pallets and trucks

“We made a decision to rationalise our range of toilet paper to make sure we could make as much as we could and to supply as many different outlets as possible,” Driscoll says. “We had to broaden the net of how many organisations we worked with from a logistics perspective. Our focus was wholly and solely that Australians had products in their house. It was a costly time for our business but it was the right decision.”

The toilet paper market is divided into household and commercial streams. If people are forced to stay home to quarantine with the virus or to work from home and eat their meals there as well, then consumer demand jumps, perhaps by as much as 40 per cent according to one US estimate, while commercial demand slumps.

On behalf of the major supermarkets, Coles sought authorisation from the competition watchdog to work together on a range of logistic, workforce, health, safety and supply issues.

The supply response was immediate, with local manufacturers pivoting to consumer lines. In some cases, suppliers began delivering to stores directly rather than the usual route of larger distribution centres. Demand at supermarkets would surge again after new lockdowns were announced.

Driscoll says the company benefited from manufacturing toilet paper locally; competitors faced higher shipping costs and delays and so weren’t able to service the elevated demand from retailers, which went on for years. She says “normal” conditions finally resumed in January last year. The company also has upgraded its storage capacity.

Of all things, why toilet paper?

At first it was an imported hysteria. Shortages of toilet paper, supplied by mainland China, had been reported in Hong Kong in February; armed thieves there had stolen pallets of toilet paper and there was a slow burn of anxiety on social platforms in north Asia and the US.

But by the start of March in Australia the toilet paper frenzy was the top trending item on the platform then known as Twitter; Google searches on the issue had risen fivefold in a matter of days. Toilet paper was flying off the shelves. Costco reportedly sold 192,000 rolls in a half-hour.

As well, defying trade conventions, by April that year, as the PC reported in a study on vulnerable supply chains, 80 governments had introduced export prohibitions and restrictions on surgical masks and face shields, medicine, ventilators, food and toilet paper.

Hygiene is the bedrock of civilisation, so when that is threatened it triggers a range of responses: fear, anxiety, panic, envy. Driscoll says hygiene is at the bottom of Maslow’s hierarchy of five needs, a psychological construct often displayed as a pyramid, with physiological needs (air, water, food, sleep, shelter) at the base and self-actualisation at the peak.

Jonathan David, an expert on hoarding and compulsive buying behaviours says that at the start of the pandemic, people also were buying other essential items such as pasta, rice and hand sanitiser.

“Everyone remembers toilet paper being the first thing to go off the shelves because it tends to be one of the bulkiest items,” he says.

“This means that supermarkets will often have less stocked on shelves in comparison to food items. It also means that it is hard to miss when others in the supermarket are carrying around their toilet paper.”

While at Macquarie University, David and two colleagues found panic begat panic. “So, if Joe Blow was walking into Coles and saw everyone walking out with toilet paper, and he noticed that the toilet paper section was half empty, he probably would’ve bought a pack or two, even though he didn’t need it,” says David, now a postdoctoral fellow in the department of psychology at York University in Toronto.

“Simply put, this turned into a chain reaction really quickly.”

As the dunny paper mania persisted, prime minister Scott Morrison called a time-out.

“Stop it. It is not sensible, it is not helpful and it has been one of the most disappointing things I have seen in Australian behaviour in response to this crisis,” he said. “That is not who we are as a people. It is not necessary. It is not something that people should be doing.”

Sitting pretty in Marrickville in Sydney’s inner west, no doubt, was then opposition leader Anthony Albanese. Childhood privation had instilled a need to plan ahead to have food on the table and pay the rent. “I’ve never run out of anything at home,” the Prime Minister told Katharine Murphy in the Quarterly Essay Lone Wolf: Albanese and the New Politics, published in late 2022 after his election victory in May. “Milk. Frozen food. Coffee. Toilet paper. Food for Toto.” Who knew the country had elected a prepper?

One misconception of the era was that only selfish people were panic buying. “Our research found that panic buying was not related to selfishness at all,” says David. “Rather, it was driven by anxiety about Covid-19, worries about shortages and, of course, seeing other people panic buy.”

David says his team’s research showed shopping limits did help reduce panic buying, particularly for people who initially panic bought a lot. “The downside to shopping limits is that they increase the perceived scarcity of products, increasing the psychological need to buy more,” he says.

In the event of a future crisis, David says it’s vital to address the anxiety head-on. “Public messaging should be reassuring – it should inform the public that there are enough supplies to go around,” he says. “However, if actual shortages do exist, this information should be communicated honestly, to reassure the public about plans to address shortages.”

According to Kimberly-Clark’s Driscoll, one of Covid’s enduring lessons is “people love toilet paper”. “We’ve never had people talk about toilet paper as much,” says the putative queen of hygiene products in the South Pacific. “Maybe consumers didn’t even realise how much they cared about toilet paper until it was more challenging to find.”

Coles Group’s Swindells says frontline workers were the real heroes of the pandemic and that one of its legacies is “we now have a playbook that you can put in place” to respond to an extraordinary crisis. Last week, when grocery demand surged as Cyclone Alfred approached Queensland, he says key relationships formed during those Team Australia days were rekindled, with government and industry working in tandem.

“We are a vast country with a small population and we have to work together,” Swindells says. “When we did that during Covid we were unbeatable. We shouldn’t need a crisis to solve national problems. I’m grateful every day that I live in the Lucky Country, but at some point we need to do more to make that co-operation our natural way of operating and rely less on luck.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout