Covid-19 pandemic delivers an insult to our culture of plenty

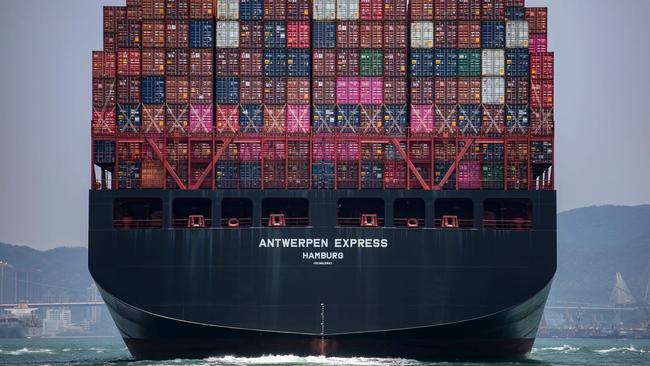

Disruptions to supply chains will affect the way the world does business and what consumers can buy.

But to be clear, these are the home countries of component multinationals, and so you could add dozens more places into this supply chain, or network, that turns raw materials into an iPhone.

Apple sells in the region of 200 million units a year.

Covid-19 has disturbed this intricate and exhaustive web. Chip shortages mean Apple can’t meet supply targets; there’ll be fewer iPhone 13s under Christmas trees, as well as longer waits for alternatives, PlayStation 5s and other prized devices. Chip scarcity affects almost every sophisticated product, most notably cars, which need up to 3000 of them to get you from A to B via voice-guided navigation, ABS braking and cabin control.

The pandemic is a five million fatality health crisis and a man-made jolt to globalisation, its Disney “small, small world” chorus strained to breaking point, first by squeezing production and then hobbling transportation.

“The pandemic triggered a massive shock to global trade,” the Productivity Commission’s Jonathan Coppel tells Inquirer. “The public health measures put in place limited our ability to consume many services, and consumers switched to buying more goods, such as household appliances.”

We hear about a “shortage of everything”, driven by cashed-up consumers’ preferences and capitalism’s failure to deliver the goods, literally. Covid-19 bequeaths a scarcity that feels like an insult to our culture of plenty, and confronts policymakers with challenges and opportunities – on regulation, workforce, industry development and security.

The Morrison government has dealt with this disorder in fits and starts. It has identified products at risk, from PPE to chemicals, and drip-fed grants to companies to cover known risks. It has a manufacturing strategy, with six key areas for uplift, from medicines to space. But nothing too costly to frighten the few Liberal rationalists that it has regressed to “picking winners”.

In “macro” land, the dearth dynamic is fuelling inflation, restraining global recovery, disrupting the trading system, and causing companies to bring suppliers closer to home. The Wall Street Journal reported that US multinationals are ditching their decades-long strategy of offshoring, outsourcing, relying on just-in-time production, and ocean shipping.

Coppel notes companies have changed the way they trade by making much greater use of digital technologies. “These shifts put pressure on supply chains, with higher freight rates being just one symptom of this. You can’t put services in a container, and more goods trade requires more containers and ships,” he says.

The cost of shipping has in some cases increased seven-fold, which won’t matter much for books or gadgets, but is going to be prohibitive for moulded plastic garden chairs. Higher prices are just the beginning. Retailers are warning of shortages of imported food items, as well as alcohol, after supply was oversubscribed by lockdown’s home mixologists.

ACCC chair Rod Sims views the shipping delay at “peak worse”, as Victoria and NSW open up. “International shipping line movements normally run lean and just-in-time, but a surge in demand and Covid outbreaks that have forced port operations to temporarily shut down have caused congestion and delays with a cascading effect across the globe,” Sims says.

Shortages are pronounced for home-building materials, pushing up the price of steel, timber, rebar and plumbing products. Input costs for detached housing rose by 8 per cent in the year to September, including a 24 per cent rise for steel. Manufacturers’ costs have jumped by 11 per cent over the year.

The price of furniture and household equipment has surged, due to limited supply and higher demand as households have been flush with government money. People are holding on to worn couches as retailers warn customers of delays and higher prices. A shortage of wooden pallets is hampering the movement of goods, and some food producers are halting lines. Sims notes strikes on our docks and by transport workers are shredding delivery schedules.

These underlying price pressures are driving financial market players, who are convinced the Reserve Bank will have to raise interest rates as early as next year. RBA governor Philip Lowe insists Australia is different and these shortages will eventually wash out. Rates aren’t moving for a few years. Treasury has a similar view, with one official telling a Senate hearing that “inflation expectations remain anchored”, so it’s unlikely cost pressures will endure or feed into a spike in wages.

At the start of the pandemic there was a shortage of face masks, and panicked shopper runs on toilet paper and sanitiser. While the initial pain was on exports, some fear an eventual calculated punishment on key inputs. It has led to calls for more sovereign capability. Others, however, are more strategic and opportunistic. If not now, when? Former Dow Chemical chief Andrew Liveris, who was a special adviser to the National Covid-19 Commission, said Australia “drank the free-trade juice and decided offshoring was OK – well, that era is gone”.

In February, Josh Frydenberg directed the PC to identify supply risks and approaches to managing them. An interim report in March found only 5 per cent of imports originated from a concentrated source of global supply, mostly China. Toys, festive decorations, Swiss watches and French champagne could be classified as vulnerable. But only 2 per cent of these goods were classified as essential to the country’s needs.

It was a blow to those seeking handouts for manufacturing self-sufficiency. Rather than moving to costly onshore supply, the PC’s solution was better risk management via alternative suppliers, strategic stockpiling and improving the rules-based trading order.

Still, Scott Morrison has responded to shortages by grants to the makers of key inputs such as medicines, agricultural chemicals and PPE, as well as a broader push for onshoring through the Coalition’s $1.5bn Modern Manufacturing Strategy. Having three industry ministers since March, however, has led to a stop-start rhythm. There’s also a multi-government effort to establish mRNA vaccine production. But it won’t be easy. The Pfizer Covid-19 vaccine contains 280 different ingredients, sourced from 86 suppliers located in 19 countries.

In July, Morrison established an Office of Supply Chain Resilience in his department. A spokesperson said the office monitors ongoing risks to supplies of essential goods and co-ordinates government advice on actions to strengthen critical supply chains.

Labor is more interventionist by inclination but woolly in its game plan. Anthony Albanese’s big move is a $15bn national reconstruction fund, providing loans and other support to new enterprises in areas such as value-adding, renewable energy, defence industries, and transport.

“Australia has the resources and brainpower to make everything from wind turbines to electric batteries, train carriages to military hardware, medicines to macaroni,” he wrote in our pages last month. Buy Australian, including through government procurement, are key pillars of his approach, which won’t appeal to the free-market purists

There’s also a tectonic shift in Joe Biden’s America. In February, under an executive order, the US President launched a 100-day review of supply for four vital products: semiconductors; minerals and materials such as rare earths; pharmaceuticals and their ingredients; and advanced batteries, like those used in electric vehicles.

The June report by National Economic Council director Brian Deese and National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan urged a revolution, to in effect re-engineer globalisation. The authors concluded America’s private sector and public policy had prioritised efficiency and low costs over security and resilience.

Deese and Sullivan found US capability had declined, while rivals such as China had not only prospered, but cornered the market for key inputs. China refines 60 per cent of the world’s lithium and 80 per cent of the world’s cobalt, two core inputs to high-capacity batteries, “which presents a critical vulnerability to the future of the US domestic auto industry”.

“We must press for a host of measures – tax, labour protections, environmental standards, and more – that help shape globalisation to ensure it works for Americans as workers and as families, not merely as consumers,” the White House report said.

Writing in the New York Review of Books, Robert Kuttner argues the report “represents a wholesale repudiation of the economic assumptions of the past several decades”. The progressive Kuttner celebrates the prospect of greater economic nationalism that began under Donald Trump, but without the bombast or nativism. More FDR and small business, less overt China bashing.

“It’s clear that Biden will have to settle for far less public investment than proposed in his original vision to ‘build back better’,” Kuttner writes. “But with this remarkable report on supply chains, we have a dramatic reversal of a half-century’s conventional wisdom in economics – a working draft of a neo-Rooseveltian strategy for shared prosperity.”

In August, the Senate’s Economics References Committee began an inquiry into Australian manufacturing, which is due to report on November 24. The industry lobby is calling for a Biden-style review to jump-start investment, with a big push coming from the ACTU and South Australian interests in the wake of the sinking of the $90bn subs contract with France’s Naval Group.

Jarrod Ball, chief economist at the Committee for Economic Development of Australia, says the PC’s work shows supply chains are long and that business is best at identifying choke points. But governments can play a role in hurrying up the return to normal. First, Ball says, they need to keep borders open and planes flying that have a freight capacity. Second, governments can reduce logistics red tape. Third is opening up the services economy.

“That’s how you get back some of the equilibrium between services and goods spending,” Ball says.

With borders closed to temporary migrants, skill shortages are already apparent, especially in the public construction mega projects. Infrastructure Australia has identified a shortfall of 105,000 skilled workers over the next five years, with $218bn of work in the pipeline.

“Put simply, a lack of workers and materials is a noxious cocktail for the construction industry,” Deloitte Access Economics partner Stephen Smith said this week.

“And with a record amount of infrastructure work set to be completed – not to mention a large pipeline of residential construction activity – it will be a stretch for contractors to deliver projects on time and on budget.”

At Senate estimates last week, Labor’s Katy Gallagher asked Treasury officials whether there needed to be “any kind of specific response to those areas of the economy that are now experiencing supply chain pressures”.

Finance Minister Simon Birmingham answered: “Not at this point and not from a short-term perspective”.

The Morrison government is conducting a second tranche of analysis into semiconductors, water treatment chemicals and telecommunications equipment as part of its $107m Supply Chain Resilience Initiative, announced a year ago. But the view among officials is that dislocations are temporary, the world will right itself, and contingencies are in place

The PC’s Coppel says the past 18 months show that supply chain disruptions come suddenly – the trigger may be a pandemic, a trade war, a financial crisis, a cyber attack, or a natural disaster – and so being both prepared and flexible are crucial.

“We should not presume that having a domestic production capability is the sole or least cost response,” he says.

Coppel maintains that the Covid-19 pandemic has served as a stark reminder that an open and predictable trading environment is vital for maintaining resilient supply chains, as it allows firms to diversify. “Crises also test the roadworthiness of trade agreements,” says Coppel, of a stressed global system that is being transformed.

Disruptions will certainly test the patience of recently liberated consumers, as delivery delays, empty shelves and “out of stock” online responses become the norm. As competition watchdog Sims advises, do your Christmas shopping now.

It takes a planet to make a vaccine, submarine, car, computer or smart phone. Consider the iPhone: designed in California, “assembled” in Shenzen, “made” everywhere. The Corning glass screen and Wi-Fi and audio chips are born in the USA. It sports a Swiss gyroscope and an accelerometer from Germany’s Bosch; a Sony camera, compass and LCD screen are Japanese; the battery is from South Korea’s Samsung.