Morrison’s censure a political stunt but an appropriate shaming

It says a lot about where major party politics is at in this country that the opposition for the most part united in voting against the censure motion. It was tribalism over good governance.

The censuring of Scott Morrison was certainly a political stunt. But that doesn’t mean it wasn’t a valuable thing to do: sending a message that his actions were inappropriate and diabolically bad for institutional democracy in this country. Not to ever be repeated.

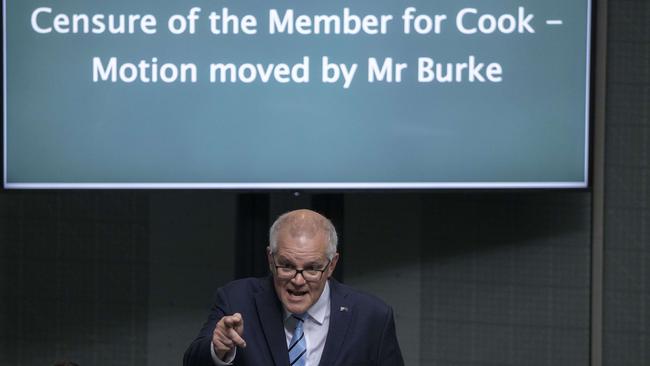

Morrison is the first and only prime minister to be censured on the floor of the House of Representatives. While censure motions are often used to score political points against opponents, a government of the day using its numbers to censure a former prime minister is unprecedented.

In this case, that motion was supported by the lion’s share of the crossbench and even a Liberal MP, Bridget Archer. Another Liberal MP, and former Morrison cabinet minister, Karen Andrews, abstained from the vote. Her portfolio was one of those Morrison took over in secret. She has publicly called for him to resign from parliament for what he did.

It says a lot about where major party politics is at in this country that the opposition for the most part united in opposing the censure motion, voting against it for the history books, with many of those same MPs going over to Morrison and offering him emotional support in the moment. Tribalism over good governance.

Censure motions are designed as an opportunity to express strong criticism on the floor of parliament. In the wake of the report by the Solicitor-General, and the findings of an independent review by ex-High Court justice Virginia Bell, it was an entirely appropriate rebuke. Appropriately unprecedented and unusual, given the unprecedented and unusual circumstances of what Morrison did.

Consider the facts: a prime minister secretly assumed co-equal control of a gaggle of ministries without the consent or knowledge of the ministers in question, the cabinet or the parliament. He did so without any form of public announcement to follow. The Governor-General went along with all of this. How he survives a formal rebuke is beyond me.

In his defence during the censure motion, Morrison raised three justifications for his actions: the crisis at the time warranted such actions; he didn’t in fact act on the ministerial powers secretly assumed (with one exception); and if anyone had chosen to inquire about what he had done, well, he happily would have owned up to the moves made.

The last of these is perhaps the most extraordinary justification. They all speak to a state of mind that is hard to get your head around. Colleagues of Morrison privately have said they think the strains of the pandemic got to him, and these actions were at least in part a consequence of that. Others simply say he has a “God complex”. The notion that a prime minister secretly does something as significant as this, which is OK because he would have owned up to the actions had he ever been called out, is patently absurd. How can you call someone out on something you don’t know about?

Besides, Morrison is the master of not answering questions. For example, when he was asked point-blank did he seek an invitation to the White House state dinner for his friend, controversial pastor Brian Houston. Yes he did, and he subsequently admitted to doing so. But at the time he refused to answer the questions, dismissing them as “gossip”.

The premise that had anyone asked about his self-appointments Morrison would have answered leads to the ridiculous situation whereby journalists are expected to ask a series of hypothetical questions at the beginning of every media conference just in case the prime minister has acted in ways that are inappropriate we don’t know about. And we know how much politicians like hypothetical questions.

The notion that it was OK Morrison secretly took over portfolios because he didn’t use the powers falls over as a defence because he actually did use the powers on one occasion – in the resources portfolio he usurped from Nationals cabinet minister Keith Pitt. Citing that he only did so once but not on other occasions invalidates the premise of the defence.

The argument Morrison fell back on repeatedly in his censure motion defence on Wednesday was the idea that no one else could understand the situation he was in as prime minister, trying to keep Australia safe during the pandemic. Therefore the secret takeover of portfolios was somehow justified, as ends justifying means.

This is a scary argument because it leads to all manner of crisis-moment forgiveness for power grabs that go against our democratic institutions and culture. But ends justifying means isn’t a new concept for Morrison or the government he led.

Not that it is easy to find a link between efforts to deal with the pandemic and the multitude of portfolio takeovers Morrison secretly engaged in. The one time he used his powers, for example, had nothing to do with the pandemic.

Taking over the Treasury portfolio while living with Josh Frydenberg in 2021 in the countdown to the budget, a full year after the pandemic began, is unfathomable. Why did he do that? Did Frydenberg do a sloppy job washing the dishes that day or taking out the garbage, such that Morrison felt compelled to add an oversight safeguard by co-opting his job? Apart from the institutional implications of this particular move, it says something about Morrison’s character in the context of the pair being so close.

The takeover of home affairs after Peter Dutton left the portfolio and once Andrews was appointed invites questions about whether doing so was a gender thing. Did Morrison worry about a woman taking charge of a national security portfolio to the point by which he was prepared to co-opt her responsibility?

There was no reason for Morrison to do what he did. The review into his conduct unequivocally concluded his actions were inappropriate and unnecessary as our system of government already had adequate safeguards were something to happen to a responsible minister – during a pandemic or at any other time.

Morrison in his self-defence said his actions weren’t against the law. As if that’s the benchmark we want for our leaders: conduct which skates ever so slightly above the illegal. The fact the recommendations from the review suggest changing the law to make what happened illegal so it never happens again says everything about this fig leaf of a defence by the former prime minister.

Censure motions for ousted figures such as Morrison are symbolic. They don’t lead to tangible consequences beyond the shame. But symbolism matters, and Morrison being censured this week for his actions while in office rules an all too appropriate line under his prime ministership.

Peter van Onselen is professor of politics and public policy at the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.