Judicial neutrality trumps Bell’s political alarm

The NSW Supreme Court Chief Justice should stick to exploring legal issues closer to home.

Do would-be regulators of speech never sleep? Whenever we’re told that current events render freedom of expression less important today than it was yesterday, or last week, or a few years ago, that is precisely when those committed to liberty must defend it.

It is especially important to do this when those leading the charge for more regulated speech should know better – learned lawyers and the like.

Let’s be clear about Sarah Abu Lebdeh and Ahmad “Rashad” Nadir. The two nurses, accused of threatening to kill Israeli patients at Sydney’s Bankstown Hospital, will no doubt face the full force of the law.

But this case has nothing to do with free speech. There is no freedom to threaten to kill Jews. No freedom to incite violence against Jews. Not to prejudge the outcome of this case, the betting is that existing laws will be handsomely equipped to deal with these two former nurses.

Can we at least wait to see how the legal system deals with them before making reflexive demands for more laws?

If these alleged crimes become fodder for calls to curb free speech, then these two “depraved” people will have done even more damage to our country. They will succeed in making us less committed to principles that make us a free and thriving democracy.

Even before this week’s shocking news, others have called for more curbs on free speech. Woolly demands might make some feel good. But they don’t help us think logically about a complex issue.

Enter NSW Supreme Court Chief Justice Andrew Bell. Earlier this month the judge said some silly things about Donald Trump, Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg’s Meta. He made ill-conceived comments about free speech, too.

Perhaps the Chief Justice of NSW is bored with his judicial role. He seems to have pitched himself into a new one as roving chief censor. The only person Bell should censor is himself. When judges wade into political controversies, they usually make a hash of it.

Worse, they risk undermining their role as a judge and the judiciary more generally.

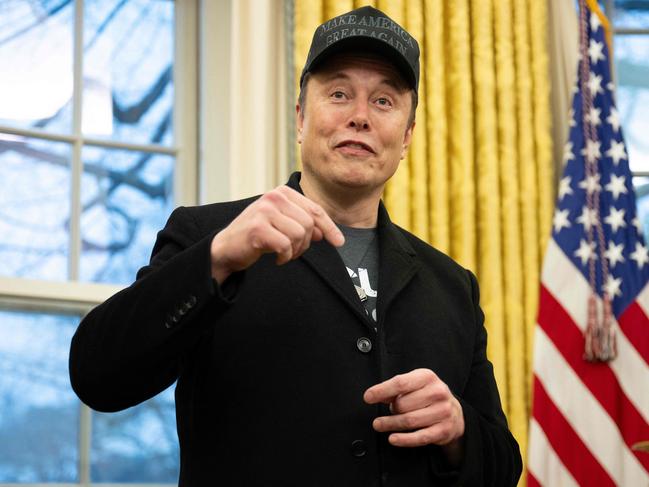

At a dinner to mark the new legal year, the Chief Justice roasted Musk as the man “who attacked the Australian government’s attempts to regulate the flow of misinformation and disinformation”. How dare the tech billionaire invoke free speech, Bell said, free speech was not absolute.

That’s a trite observation. No freedom – not even the right to life – is absolute. Bell is anxious about, and I’m paraphrasing here, the amount of online crap.

Aren’t we all? The question is what we do about it; in particular, how do we deal with conflicting rights? Bell offered no clue.

Perhaps Bell didn’t realise that Musk was in solid company objecting to the federal government’s plan to regulate speech.

Many classical liberals were opposed to the Albanese government’s proposals to regulate information. The bill was contentious for its wide application, for the powers it proposed giving to a bureaucrat.

It’s worth noting that the proposed bill that Bell seems to support didn’t go anywhere. For good reason. It was controversial.

Why would a judge imagine his views about regulating speech trump others? Some cynics might think he’s signalling to a Labor government his availability for the next High Court vacancy.

We’re less cynical. We can live with self-indulgent judges. What’s more problematic is when judges join policy and political fights they have no business being in.

Let’s say some form of misinformation laws are enacted. A defendant is in the NSW Supreme Court arguing that the new laws breach the implied right to political communication in the Australian Constitution.

Let’s say Bell is presiding. This would be a big important case raising sexy constitutional issues about when state and federal governments are prohibited, by this implied right, from passing laws or take actions that would breach the implied freedom.

This Chief Justice has signalled he’s in favour of regulating misinformation. That’s a problem, not just for the defendant but for the administration of justice.

At the dinner address, Bell presumably included himself when he said lawyers should be critical thinkers. A judge should be super careful about defining key terms. While we can guess that Bell doesn’t like “misinformation” and “disinformation”, we have no idea how he defines those terms. In truth, like “fake news”, these are loaded terms, often used to shut down information that should be free to circulate in a free society.

Even dumb and offensive ideas should get a run in a free country. You don’t need to be John Stuart Mill to know that what makes us a healthy democracy is our ability to argue against the dumb ideas, offensive ones too, allowing them to be aired so we can explain why they are wrong.

If the law steps in when we, as citizens, should be doing the work, we will lose the skills to confront bad ideas and foul words.

The NSW Supreme Court judge doubled down on his dislike of misinformation, complaining about Meta’s abandonment of “fact checking”. There’s a different view. Meta’s so-called fact checking had become a censorship tool.

Even Mark Zuckerberg agreed, saying: “We will allow more speech by lifting restrictions on some topics that are part of mainstream discourse and focusing our enforcement on illegal and high-severity violations.”

Bell’s eagerness to tell the world he favours speech control wouldn’t matter if he were Joe Citizen. But a judge serves the administration of justice best when he’s a neutral arbiter of the law, not a frustrated policymaking politician.

Alas, Bell wasn’t done jumping on political landmines.

Next, he condemned presidential pardons, in particular Trump’s first day pardons for the January 6 rioters. Many, including me, might agree this was a bad exercise of the pardon power. But it’s not a rule of law issue. Presidential pardons are legal.

Bell should take up his frustrations with the founders of the US constitution. Or the Americans states charged with amending the constitution. The views of an Australian judge are neither here nor there.

It’s to be expected that Trump derangement syndrome would afflict some Australian judges. What judges say in private about Trump et al to their partners, friends and therapists is their business. When they take it public, we will ask why they can’t find important matters closer to home that challenge the rule of law. There has been plenty to choose from in recent years.

Not done with political forays, Bell condemned Musk for appearing to “exercise substantial but unaccountable political power”. Let’s put aside that the Chief Justice sounded like an echo chamber for US Democrats such as Jamie Raskin, who told a recent protest “we don’t have a fourth branch of government called Elon Musk”.

As William McGurn wrote in The Wall Street Journal this week, Musk can be sacked next week by the elected official who appointed him – Donald J. Trump.

That’s more accountability than heads of departments face, said McGurn.

Or judges. In fact, judicial accountability took an interesting turn this week when the High Court decided that all judges of courts referred to in section 71 of the Constitution are immune from civil suits arising out of acts done in exercise of their judicial function or capacity.

Being a judge is not a bad gig. Judges don’t have be boring when speaking publicly. High Court justice Robert Beech-Jones gave a tremendous historical speech last year about 10 important lawyers. The list included Hans Litten.

As Beech-Jones said, when Litten was just 28 he “conducted one of the most famous cross-examinations in history and he was not even 30 when his life was effectively over for doing so”. The man in the box was Adolf Hitler.

Bell was right to condemn anti-Semitism in his February 6 address. Leaders of every profession, every industry, every one of our elected representatives should do it more often. But it’s a shame that a chief justice chose to turn moral condemnation into a quasi-enunciation of the law when he claimed: “It is a perversion to seek to justify anti-Semitic speech as an example of freedom of speech.”

The judge does us a great disservice by not acknowledging that there is robust and healthy debate about what constitutes anti-Semitism. Words and their definitions matter. The definition of anti-Semitism set down by the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, accepted by the US State Department and other governments, includes a broad range of abhorrent acts. But the listed acts are not equally abhorrent.

Anti-Semitism includes calling for, aiding, or justifying the killing or harming of Jews in the name of a radical ideology or an extremist view of religion. The criminal law deals with this class of anti-Semitism. The IHRA definition of anti-Semitism also includes those who hold Israel to “double standards by requiring of it a behaviour not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation”.

This might be wrong to do but it’s not illegal. Not yet. And neither should it be. Could it be legitimate to hold Israel to a higher standard of human rights and legal protections than, say East Timor, because Israel is rich and educated?

People of goodwill can and do differ on such matters and the difference should not be labelled with deeply judgmental words. These are exactly the sorts of allegedly anti-Semitic sentiments that I will justify as free speech. I may or may not agree with them. But if freedom of expression applies only to people with whom we agree, then we won’t be living in a free country for much longer.

Bell is right that there are reasons to worry about the rule of the law and the state of our democracy. But his obsession with politics appeared to get in the way of exploring legal issues closer to home. To help settle his nerves about the US, the chief judge might consider a subscription to The Wall Street Journal.