Message from Beijing: don’t rock the boat

China will fight against AUKUS every way it can. The strategic pact transforms Australia’s role in the Indo-Pacific and proving our seriousness of intent to the Americans is needed to make it work.

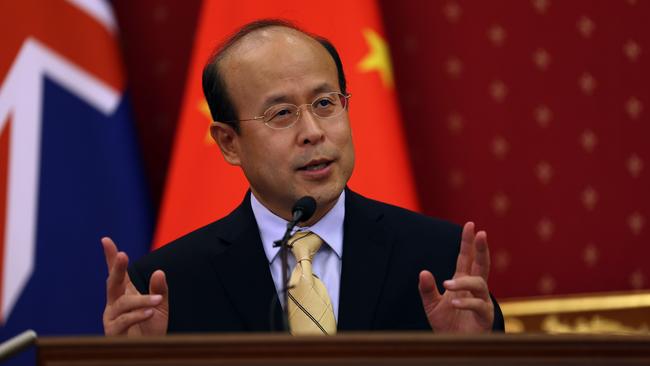

At his Lunar New Year media conference this week, China’s ambassador in Canberra, Xiao Qian, was mystified why Australia wanted nuclear-powered submarines via the AUKUS agreement.

“I don’t think it’s constructive, I don’t think it’s helpful, especially when you’re targeting China as a potential threat or adversary,” he said. The nuclear-powered submarines would be “an unnecessary consumption of Australian taxpayers’ money” and “even more serious” set a “bad example” of how a nuclear-armed state, such as the US or Britain, would transfer nuclear material to non-nuclear Australia.

If AUKUS works, the plan is that Australia will get its first nuclear-powered sub in the mid to late 2030s. We will not have the planned eight Australian-built submarines in the water before the early 2050s.

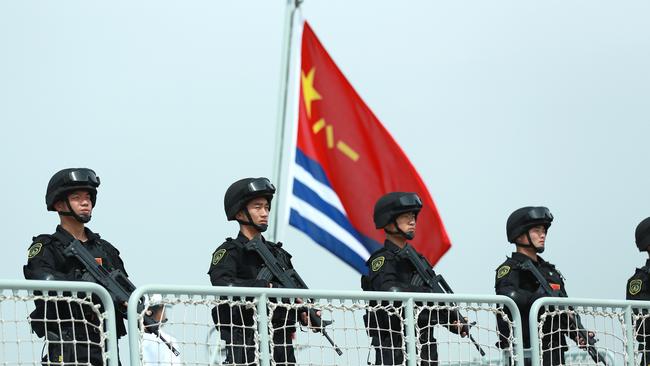

Contrast that with China’s navy, which has 12 nuclear-powered boats (six with intercontinental nuclear missiles) and 44 diesel-powered boats. China will have between 65 and 70 submarines in the mid-2020s, updating its fleet with one to two new boats a year.

According to the US Department of Defence’s November 2022 report to congress on Chinese military power, Beijing has the world’s largest surface navy.

China is building its third aircraft carrier and new batches of guided-missile-carrying destroyers and frigates, launching more ships every one to two years than the entire tonnage of the Australian navy. China also is building international logistic facilities to enable navy and air force operations across vast distances.

The Pentagon says Beijing has “likely considered” Cambodia, Myanmar, Thailand, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan, Sri Lanka, United Arab Emirates, Kenya, Seychelles and Tanzania as logistic hubs in the Indo-Pacific.

The report adds Vanuatu and Solomon Islands to that list where “the PLA is most interested in military access” along sea lines of communication.

As for nuclear weapons, Beijing has an estimated 400 operational warheads and will “field a stockpile of about 1500 warheads” by 2035.

Although hardly reported in Australia, none of this is secret: The Pentagon draws on mountains of public information about Chinese military power, much of it from the People’s Liberation Army. Add the inflammatory speeches of Xi Jinping telling the PLA to prepare for war, Beijing’s militarisation of the South China Sea and “wolf warrior” rhetoric, recently toned down from incendiary to merely patronising.

Yet, according to ambassador Xiao, it is Australia that is at fault, risking nuclear proliferation with pointless military acquisitions.

The contrast in Xiao’s presentation could hardly be clearer. On the one hand we have a “stabilising” relationship where “you have more encouragement to the Chinese economy, to the Chinese customers to come back for a stronger appetite for Australian products”. But AUKUS is a problem and “the submarine purchase under AUKUS is an even worse idea”.

Beijing hates AUKUS because it complicates its plan to dominate the Indo-Pacific. US undersea technology has an edge the PLA has not blunted. The biggest risk to Chinese maritime power is American and allied maritime power.

China will fight against AUKUS every way it can, including by saying it puts Anthony Albanese’s prized “stabilised” relationship with Beijing at risk.

By his own choice the Prime Minister is locked on to AUKUS and the March announcement of the “preferred pathway” for the Australian navy to acquire nuclear-powered submarines.

Albanese could have made a politically tough call not to support Scott Morrison’s surprise announcement of the AUKUS partnership in September 2021. Had he chosen, Albanese might have used Labor’s eight months in office finding an AUKUS off ramp – for example, buying more missiles and aircraft from the US but backtracking on submarines.

The Prime Minister instead has made the right but difficult call to go for nuclear propulsion.

Strategically, we need the closest alliance with the US in the face of China’s military build-up. Militarily, the Australian Defence Force is undergunned; it needs the deterrent power that nuclear-powered boats will (eventually) deliver.

Delivering on AUKUS presents some serious problems: We have yet to see any cost estimates but building and operating nuclear-powered subs will be frighteningly expensive. In my view it will add $20bn annually to the defence budget, lifting spending from 2 per cent to 3 per cent of gross domestic product.

Second, Labor wants to claim a win on China policy, allowing Albanese to celebrate the special relationship established by Gough Whitlam’s opening to Beijing in 1972. AUKUS complicates that aspiration: we are not buying nuclear subs to deter PNG.

Because of China’s own assertive actions, Australia’s relationship can never go back to the happy days of uncomplicated money-making. That’s a tough message for the government to explain.

The third AUKUS problem is rising American expectations about our performance as an ally.

Our alliance with the US has been a sweet, low-cost defence deal for the generation since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Spending a good deal less than 2 per cent of GDP bought a small, modestly armed ADF able, at a stretch, to stabilise East Timor and to deploy small units to the Middle East.

But that minimal investment does not defend Australia against a potentially hostile global power wanting to dominate the region. We look to the alliance to protect us from that. AUKUS is Washington’s way of telling Australia to step up militarily.

A more independent defence posture ironically means we must do more to meet alliance expectations. Forget the rhetoric about “100 years of mateship”; AUKUS challenges Canberra to show if we are really serious about pulling our defence weight.

Last Tuesday I wrote in The Australian: “Two former Australian prime ministers, Malcolm Turnbull and Kevin Rudd, are on the recent public record vigorously opposed to the nuclear propulsion proposal.”

I have since spoken with both men and acknowledge that their separate positions on the nuclear issue are more nuanced than that. Neither is opposed to nuclear propulsion per se. Both make the case that Australia’s industrial capacity to support a nuclear propulsion system is critical to make progress on AUKUS.

Both former PMs want to see clarity around expectations that the US (or Britain if it was selected as the submarine provider) would have on Australia’s operational use of the subs.

It is publicly known, of course, that Rudd and Turnbull were highly critical of the way in which the Morrison government ended the submarine program with France. There are differences of approach but they ask if it would not have been better for Australia to explore nuclear propulsion with France.

A degree of political agnosticism about whether the navy needed nuclear propulsion was understandable at the time of the AUKUS announcement in September 2021 because the Defence Department did a clear backflip on propulsion. Before AUKUS, the Defence view was that diesel/electric submarines would deliver a “regionally superior” submarine.

Advice to that effect appears to have been delivered to Rudd at the time of the 2009 defence white paper and to Turnbull as he considered submarine options in 2016.

Defence’s change of mind happened because President Joe Biden opened access to the closed world of nuclear propulsion.

The Morrison government did not raise the issue of French nuclear propulsion because Paris would most likely have agreed to transfer the technology if that would have saved the project. Morrison handled the French badly but Albanese can thank the gods of nuclear physics that the chance to switch to AUKUS didn’t happen on his watch.

The question of the AUKUS partners’ operational expectations of Australia remains an important issue. That is: what will Australia do with its nuclear-powered subs?

Following reactions to his letter to Biden that the nuclear-powered subs deal risked pushing the US’s industrial base to “breaking point”, US senator Jack Reed late last week made several comments on social media underlining his support for AUKUS.

One statement read: “Importantly, AUKUS also lays the foundation for the most significant integration of our undersea and other military capabilities ever achieved. I am encouraged by the progress our nations have made.”

“Integration” is the sensitive word. Close co-operation on critical technology implies a closer alliance and the likelihood of joint responses to aggression from Beijing – against Taiwan, for example.

Washington will not share critical technology in the expectation that Australia will sit out a conflict with China, but this just reinforces an existing expectation.

Australia’s intelligence co-operation, shared military technology such as the Joint Strike Fighter, cyber offensive and defence actions, the US Marine Corps deployments in Australia’s north – these are all down payments on the expectation of joint military action when needed.

Canberra will rightly say that what happens on our soil and what we do with Australian-flagged subs are sovereign matters. Deep down, though, we know where we stand. Washington knows, too, and so does Beijing.

As reported in The Australian on Thursday, Adam Smith, the ranking member on the US House of Representatives Armed Services Committee, pointed to an urgent need to revise American “technology export controls” to make AUKUS succeed.

Congressman Joe Courtney, a frequent participant in the Australian-American Leadership Dialogue, has emphasised that “the need to remove legal impediments to advanced nuclear technology-sharing between the three countries is screaming out for action”.

Australia could not expect a more promising start than the positive reputation we enjoy with congress, but changing US laws and ways of doing defence business will take an enormous effort.

The failure of the submarine project with France is a case study in how our leaders can talk the talk about strategic co-operation but fail to deliver on the practical realities of making co-operation work.

We have not yet grasped the implications of being all-in on AUKUS. It transforms Australia’s role in the Indo-Pacific. Proving our seriousness of intent to the Americans is what’s needed to make AUKUS work.