China’s geared for a fall down the rabbit hole

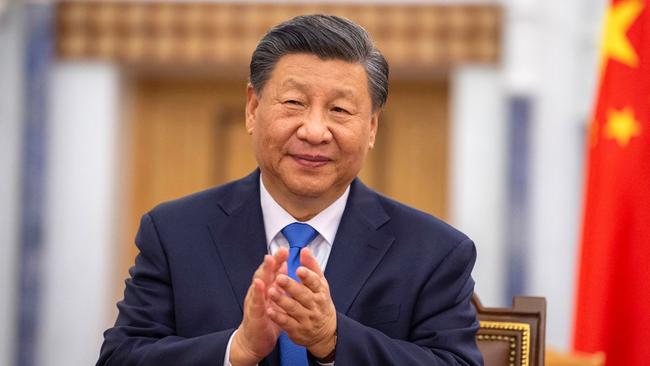

Despite Xi Jinping’s rhetoric, Beijing faces a barrage of social problems as the country’s economy flatlines heading into the Year of the Rabbit. And if he invades or blockades Taiwan, 2023 could quickly replace 2022 as the worst year of his life.

Xi Jinping begins 2023 with an in-tray stuffed with problems.

Covid-19 is spreading across China with unforgiving speed. The Chinese economy is in awful shape. Washington’s new House of Representatives is pledging to get even tougher on Beijing.

All this comes after 2022, the most straining year in Xi’s decade in power.

“The light of hope is right in front of us,” he said in a New Year’s Eve address to an exhausted nation.

Even Beijing’s censors seemed to want 2022 to be over. Shortly before Xi’s speech, they purged a retrospective year-in-review video produced by a Chinese news outlet, which contained scenes of Shanghai’s chaotic lockdown.

But the new year brings new problems. Those challenges suggest 2023 could be an even bigger headache for China’s 69-year-old “chairman of everything”.

Living with Covid

The collapse of his signature “zero Covid” policy is the most pressing problem for China’s leader. Some are euphoric about the abrupt dismantling of Beijing’s hard-line “zero Covid” apparatus.

“I must – must! – travel this year!” says Chen Weiwei, 28, an office administrator in Shandong. This year she wants to visit Australia, where she has friends from her university days. The trip has already been postponed for three years.

“I vow not to stay in fear of the epidemic any more,” she tells Inquirer.

After a ghostly month, traffic jams are returning to China’s major cities. At Sanya, a beach town off China’s south coast, resorts are packed with guests who have recently recovered from Covid. At the same time, hospital wards are crowded with elderly patients, as Xi almost acknowledged in his New Year’s speech.

“We have now entered a new phase of Covid response where tough challenges remain,” he explained.

Only 66 per cent of Chinese over the age of 80 have had two vaccine jabs. A campaign to encourage the hesitant began in earnest only after Omicron began sweeping the country in November, too late for many.

Funeral homes in China’s biggest cities can’t cope with the delivery of bodies. Families who can afford to are paying huge premiums on a ghoulish black market.

“My neighbour had to pay 30 thousand yuan ($6400) to pay for her mother’s body to be cremated,” says one Beijinger.

Health experts fear things will get even worse in rural China in the coming weeks as the biggest migration of people in the world takes place ahead of the Lunar New Year holiday.

“What we’re most worried about is that it’s been three years and people haven’t gone home to spend the new year,” warned Jiao Yahui, head of the National Health Commission’s medical administration bureau. “There could be a retaliatory rush of people from the cities to the countryside,” she told party state media.

Supplies of Pfizer’s lifesaving Covid-19 antiviral drug, Paxlovid, are hard to get for even China’s wealthiest. They are almost impossible to source in rural China, where the country’s poorest are instead encouraged to take traditional Chinese medicine.

Well over one million Chinese people are expected to die in the outbreak, a personal tragedy for families across the country. Many are furious about the haste of China’s pandemic policy change.

It will be a humbling few months for the “commander-in-chief” of China’s war on Covid.

Age of slow growth

Much of Xi’s 2023 will be taken up with trying to mend China’s battered economy. Youth unemployment is just under 20 per cent, consumer sentiment is depressed and the property sector remains in a nationwide slump.

China’s propaganda machine has gone into overdrive to stress that things will be much better now that snap lockdowns and travel restrictions have ended. Xi was boosterish in his New Year’s address, pointing to “booming” free trade zones in China’s south and “gushing” innovations along the country’s coast.

“The Chinese economy enjoys strong resilience, tremendous potential and great vitality,” he said.

But many Chinese factory owners grumble that the economic damage will linger.

“You can’t restart a factory like switching on an electricity switch,” one tells Inquirer.

“You need to make plans for months, even for years, co-ordinating with your downstream and upper-stream clients.”

The International Monetary Fund has estimated Chinese growth last year was about 3 per cent, the second-lowest level since 1977. Xi’s top economic advisers are reportedly aiming to hit 5 per cent growth in 2023. Their blueprint plan will include policies that will “boost the real estate sector and re-instil confidence among entrepreneurs”, according to The Wall Street Journal.

Many outside of China think that is unrealistic. Dan Rosen and a team at the Rhodium Group, a research firm, argues that China has entered “the age of slow growth”, with its decades of rapid expansion now consigned to history: “Zero-Covid was just one of many brakes on growth, and the others will not vanish with a wave of Beijing’s policy wand.”

A thicket of structural problems remains. China’s working-age population has shrunk in the pandemic years. Beijing’s economic reform agenda has stalled, hampering productivity growth. The financial system is saddled with non-performing loans.

And following years of assertive foreign policy, Xi and his leadership team are confronted with an international environment that increasingly constrains China’s access to foreign capital, markets, technology and talent.

Rosen thinks growth in the range of 3 per cent a year would be a sustainable target. That is far from disastrous, but it is a humbling change of pace for Beijing. More troubling is the growing pool of economists who question whether the Chinese economy will ever overtake that of the US as the world’s biggest.

Foreign relations

Xi will resume international hosting duties this year, one part of being China’s leader for life that he seems to particularly relish.

“Over the past year I have hosted quite a few friends, both old and new,” Xi said in his address.

The stream of guests has already started this week with Philippine President Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos. Expected soon is French President Emmanuel Macron and New Zealand Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern. A visit by Anthony Albanese is still to be confirmed. In September Xi, a keen sports fan, will oversee the incongruously named 2022 Asian Games, which were delayed by a year because of Covid.

An even more important exercise in Chinese soft power will be the 10th anniversary of the Belt and Road Initiative, Xi’s signature foreign policy idea. He will be keeping a close eye on which international guests turn up.

US Secretary of State Antony Blinken is scheduled to visit Beijing early in the year.

He will encounter a Chinese leadership still bristling at what it calls the US’s “erroneous China policy”.

“We call on the US side to change its course,” Xi’s top foreign policy adviser Wang Yi recently urged, beginning a new year with an old refrain.

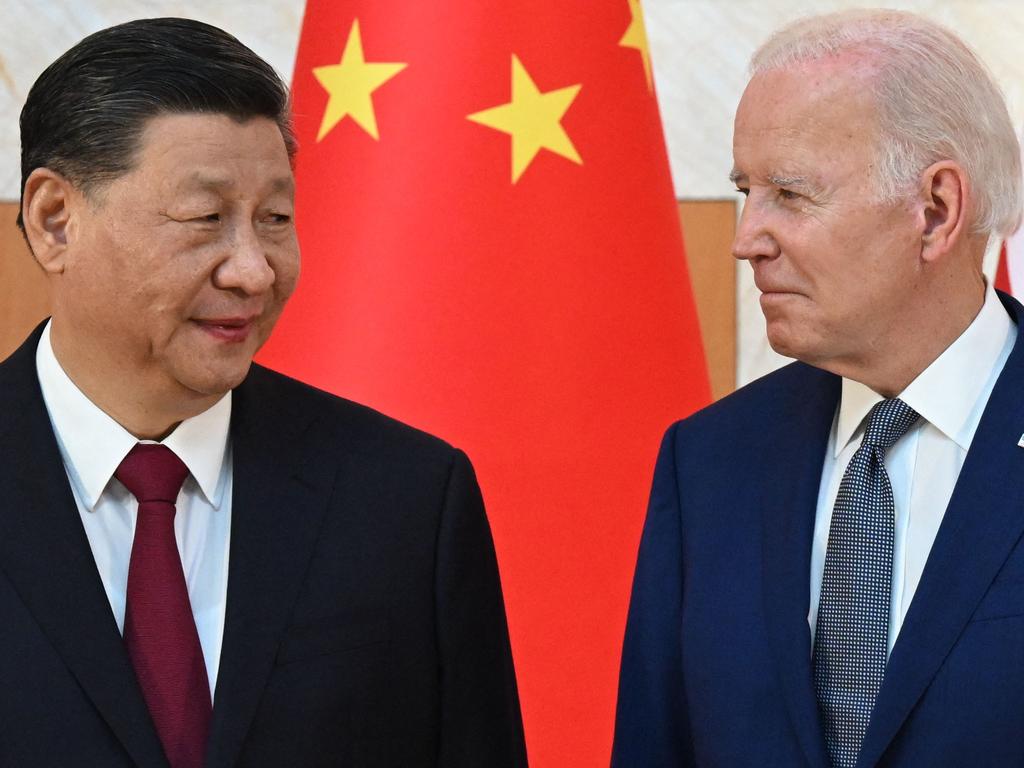

While a tense China-US relationship will continue, some respected analysts predict Xi and Joe Biden will each be keen for things to stabilise.

“I would be reluctant to suggest that the relationship will improve … But for each leader’s own reasons, I think that they have an incentive to dial down the heat a bit in the coming year,” Brookings Institution Chinese foreign policy expert Ryan Hass says.

The “no limits” partnership between Vladimir Putin and Xi will continue. Putin will likely attend the Belt and Road celebration in Beijing, while Xi has already been invited to Russia early this year. Throughout the past year, many had hoped that China would restrain Putin on Ukraine or limit flows of Chinese money into his war chest.

“Both hopes are not supported by data and are rather in the territory of magical thinking,” says Alexander Gabuev, a senior fellow at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace.

Another marker of their close relationship will come on June 15, Xi’s birthday. In 2019, Putin gave China’s smiling dictator a trove of Russian ice cream as a birthday gift. The Kremlin no doubt will be preparing something commensurate for this year’s occasion: Xi’s 70th.

What about Taiwan?

There is one clear way this year could replace 2022 as the worst of Xi’s rule. He could invade, or blockade, Taiwan. The record sortie of 71 People’s Liberation Army fighter jets that buzzed around Taiwan on Christmas Day was an ominous sign.

An expected trip to Taiwan by the new Republican US house Speaker will surely be met with a round of PLA intimidation, as happened when Nancy Pelosi visited in August.

And the Taiwanese presidential cycle ahead of an election in January next year will spur Beijing to dial its coercion machine up to 11.

However, there are sound reasons to believe Xi won’t do anything too dramatic in the year ahead. First, Beijing’s aggressive posturing has prompted firm policy responses from Washington, Taipei, Tokyo and beyond. Recently, Biden authorised $US2bn ($2.9bn) in loans to Taiwan to buy US-made weapons.

Just before the New Year, Taiwan’s President Tsai Ing-wen increased compulsory military service to one year from four months, part of the liberal democracy’s ongoing effort to make itself a pricklier target.

Beyond the difficulty of the military operation, there is the global economic devastation a blockade or invasion would unleash. Conflict over Taiwan would dwarf the impact of Putin’s Ukraine invasion, with some estimates forecasting more than $3 trillion in economic devastation to the global economy.

A report prepared by China’s Ministry of Public Security and Ministry of State Security after Putin’s Ukraine invasion – and leaked to Nikkei Asia – indicates that Beijing understands this dilemma. “If the US and allies move to slap sanctions our country will return to a planned economy closed off to the world,” the report says. “There is a high risk of (China) facing a food crisis.”

It was citizen unrest that forced Xi to end his “zero Covid” dogmatism. The aftermath of a Taiwan conflict would make Xi’s end of 2022 troubles look trifling.

There was no sense of urgency in Xi’s New Year’s Eve address, just the standard dismissal of the wishes of Taiwan’s 23 million citizens: “I sincerely hope that our compatriots on both sides of the strait will work together with a unity of purpose to jointly foster lasting prosperity of the Chinese nation.”

It will be a good year if he is still using such anodyne language when he reads his Zhongnanhai teleprompter in 12 months.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout