China’s myth of Communist competence

Mr Xi’s climb-down from his signature zero-Covid policy, and the broad and poorly controlled spread of the virus, has exposed the weaknesses of China’s social safety net. The public demonstrations since November are signs of underlying discontent. The participation of the well-off and normally passive urban populations affirms that Mr Xi can’t expect to maintain political control if he continues to impose such authoritarian restrictions.

As Simone Gao recently wrote in these pages, the end of zero Covid was in large part an admission of the government’s unsustainable financial situation. In early December, Beijing said local governments would be responsible for the cost of daily Covid testing. These already distressed institutions were put in charge of the healthcare emergency in addition to their responsibilities for education, unemployment insurance and retirement. They are also still expected to stimulate economic growth through building infrastructure and subsidising local industries.

Achieving those goals would be difficult in the best of times. But China’s local authorities have been operating with one hand tied behind their backs, thanks to Mr Xi’s economic policies. More than 40 per cent of local government revenue in recent years has come from land sales to real-estate and industrial developers. That led to one of the global economy’s largest bubbles, which Mr Xi attempted to deflate by forcing developers to deleverage their balance sheets and limiting any government bailout of private real-estate firms. The crisis has devastated the government’s balance sheet and contributed to the economy’s slowing. Unemployment crept up to 6.7 per cent in the 31 largest cities in November and is in the high teens for the young.

Few of China’s development needs can be met by the overmatched leadership and faltering finances of local governments. The urban-rural gap remains enormous in poverty, nutrition, education and economic opportunity. Healthcare coverage is weak and forces massive precautionary saving – typically more than one-third of disposable household income, compared with high single digits in the US. Water shortages and environmental damage can’t be rectified by overburdened local governments.

As it usually does, Beijing is trying to reinvigorate growth through infrastructure development, permitting local governments to lend more to real-estate developers and increasing exports. The first two likely won’t achieve much. Such capital investment can’t sufficiently drive the economy, in large part because of the country’s ageing population and overbuilt housing and transportation networks. The government must turn to exports because consumer demand is repressed by the need to save for medical care and retirement. This explains why Mr Xi has been so eager to lower the temperature with Western importers.

The Biden administration has signalled its willingness to work with China to manage the current crisis, from facilitating solar-product imports to applauding Beijing’s promises at the COP27 climate conference. The White House is slow-walking sanctions on TikTok and establishing only limited controls on US investment in China.

A better approach would be to remain on the offensive against Mr Xi’s mercantilism and find ways to undermine the Communist Party’s narrative of competence and inevitable global dominance. This would include the Trump administration’s $US300 billion in tariffs on Chinese exports and limiting Chinese acquisition of Western technology. It would also limit US investors’ ability to finance research and production of sensitive technologies in China – as proposed by Sens. Bob Casey and John Cornyn – and delist Chinese companies on US stock exchanges if they don’t comply with Securities and Exchange Commission auditing requirements.

Beijing’s failures give the US and its partners an opening to persuade potential allies, especially in South and Southeast Asia, to dismiss what Mr Xi calls the gravitational attraction of the Chinese model. The US has been the leading investor in Southeast Asia in recent years and could further boost ties by reopening negotiations to join the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership.

The Biden team should also call out China’s human-rights abuses, exploitation of local resources, and the corrupting influence of the Belt and Road Initiative in Africa, South America and South Asia. Instead of lauding China for dodgy commitments on climate change, the US could talk about the environmental harm from China’s economic model. China’s CO2 emissions are well above those of all members of the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. It mines more coal than the US, the European Union and India combined. And it plans to build, or is already constructing, more new coal-fired electric plants than the rest of the world combined.

Mr Xi’s narrative of economic and political competence continues to be exposed as myth, allowing the US to work with allies to remind unaligned nations of the value of the Western model. It also should help convince our often recalcitrant allies, in the EU and elsewhere, not to relent on combating Chinese mercantilism.

Mr Duesterberg is a senior fellow at the Hudson Institute and author of Economic Cracks in the Great Wall of China.

The Wall Street Journal

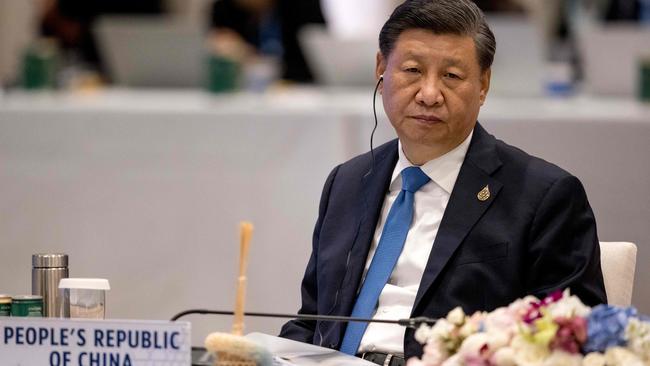

Xi Jinping doubtless expected to celebrate the New Year by touting the superiority of his authoritarian economic and governance model. Instead, he is trying to manage a healthcare crisis, a weakening economy, and political protests. These vulnerabilities – each attributable to the Chinese Communist Party under Mr Xi’s leadership – allow the US to combat the party’s mercantilist policies and debunk its narrative that China’s rise to global dominance is inevitable.