How long is too long to mourn the love of your life?

Writer Geraldine Brooks was barely into the brutal adjustment of life as a widow after her husband of over three decades died, when she detected the sense she should be ‘over it’.

How long is too long to mourn the love of one’s life?

A month? A year? Two years?

Writer Geraldine Brooks was barely into the brutal adjustment of life as a new widow when she detected the sense that she should be “over it”.

“For a short while, everyone treats you differently, and then they expect you to snap back, and they get very impatient if you’re not acting normal,” says Brooks, 69, in an interview with Inquirer.

“I don’t think people understand complicated grief, and how long it can take and how it comes and goes in waves.

“You can be doing well, venturing into the world, and then it comes and crashes over you and you’re back to the beginning again.”

Brooks suffered a tremendous loss when her husband of more than three decades – war correspondent, writer and raconteur Tony Horwitz – died suddenly on a footpath in Washington DC.

She was ather lovely, shingled home on the island known as Martha’s Vineyard, off the coast of Massachusetts, when a caller rang to say that Horwitz had “collapsed in the street” and had been “taken to hospital” during a book tour.

She waited for them to say “and we had to operate” or something like that, but instead they said: “He’s dead.”

It was impossible to get her head around.

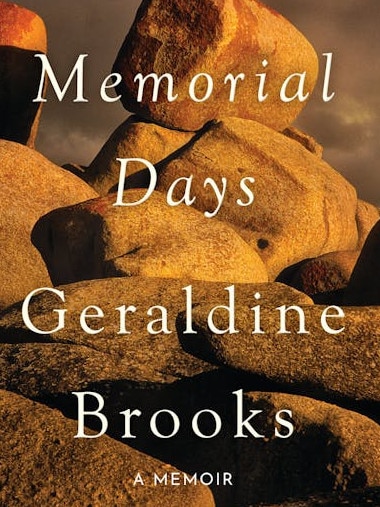

It was May 27, 2019 – Memorial Day in the US. (Brooks’s new memoir, about her love for Horwitz and the loss of him, is called Memorial Days in honour of that date.)

She had to deal with shock as well as grief because “Tony was only 60, younger than me, and exercising at the gym six days a week, and he seemed to be in radiant health, so his death was completely unexpected”.

That said, can anyone really prepare for the loss of their dearest love? “Oh, god no,” she says. “Just, no.”

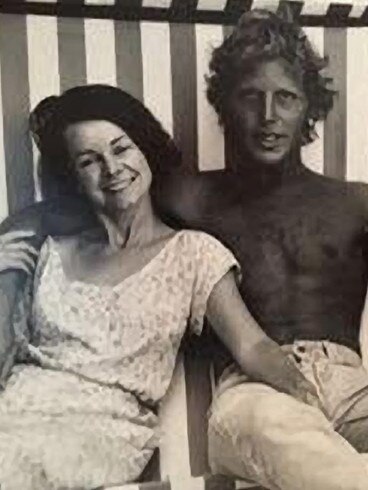

In her book, Brooks describes how she and Horwitz met in 1982 at a party in Manhattan. Although born and reared in Sydney, she had won a scholarship to the Columbia University graduate school of journalism, and Horwitz, an American, was at the same university.

“We were lucky that we didn’t beat around the bush … we realised that we were right for each other,” she says.

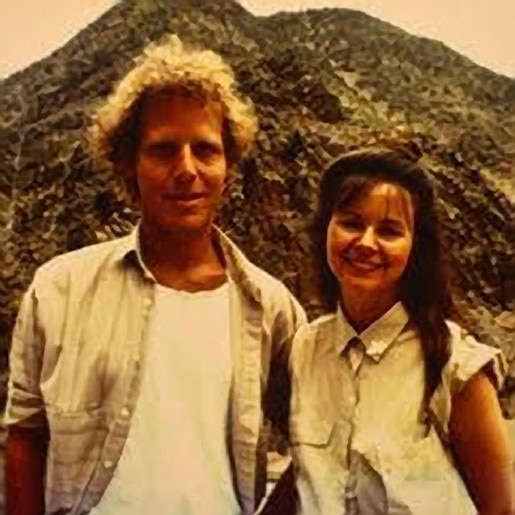

They became foreign correspondents, covering the Middle East and Africa, living an exciting life and keeping a duffel bag stuffed with a bulletproof vest for him and a full-length hijab for her in the hallway.

Brooks turned her attention away from fast-paced journalism after the birth of their first son, Nathaniel, in 1996 and began writing beautiful books instead. (Her novel March, about the husband and father in Louisa May Alcott’s Little Women, won a Pulitzer prize in 2006.)

They adopted a second son, Bizu, from Ethiopia in 2008. He was already five when they met, and there’s a lovely description in Memorial Days of Horwitz “carrying Bizu on his shoulders for a year” while the once-anxious boy settled into American life. The couple became “empty-nesters” earlier than they expected after Bizu decided he want to leave home to go to boarding school at the age of 16.

“I was sorry he chose to go,” Brooks writes in her memoir. “I came late to mothering and I loved it. But Bizu had talent … it seemed churlish to stand in his way.”

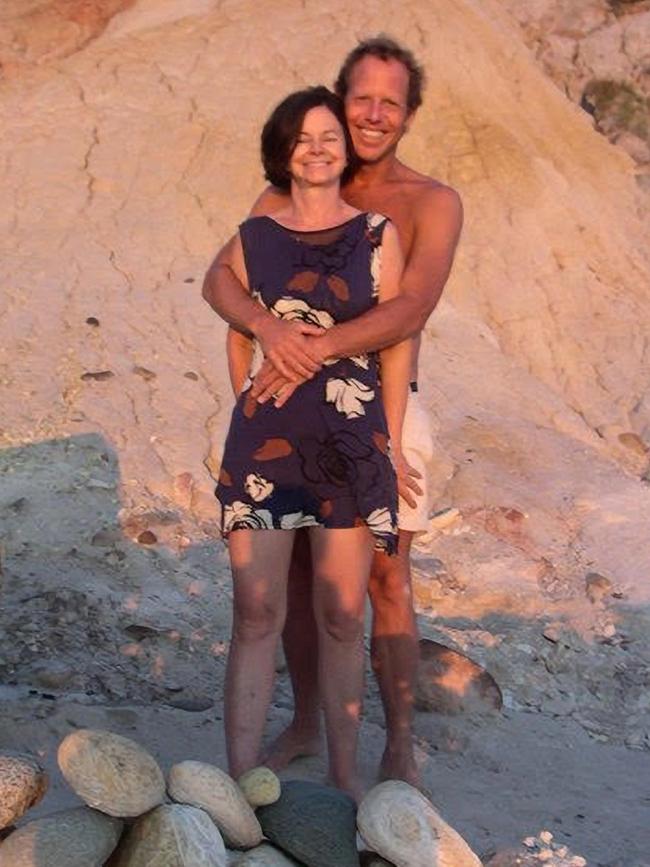

It turned out to be a blissful time for the couple, “with no one to consider but ourselves”. Spontaneously, they would head out to dinner, a movie or to walk the cobbled laneways of ancient cities while discussing future travel.

“What big plans we had,” she writes. “How many adventures there would be.

“Plans … oh, those.”

Brooks says she suppressed the howl that rose in her chest on receiving news of Horwitz’s death “because I was alone, and no one could help me”.

Their boys were away – Nathaniel was on a plane, en route to Sydney, and Bizu was with his classmates – and each had to undertake frantic journeys, as the boys tried to get home, while Brooks tried to get to Horwitz.

She was at first baffled, then catatonic, when somebody handed her a plastic bag that contained what were described as Horwitz’s effects (his shoes, a crumpled newspaper, his phone, glasses and wallet).

She opened the wallet to find a receipt that captured details of his last meal (eggs, OJ and coffee, which he’d paid for, just before he collapsed outside the diner).

When she was finally able to see him, she noticed that his fine hair was still a little damp from the washing process, and when she stroked his cheek, it was “cool, like he’d come out of the ocean, after a sunset swim”.

“My love,” she kept repeating. “My love.”

At the time of his death, the couple were “as much in love as we’d ever been” and she felt robbed of the opportunity to properly say goodbye.

(Their final, tender words to each other, before Horwitz’s death, are in the book; I won’t reveal them here but it’s a nice reminder to always say “I love you” or something like it when your loved one leaves the house. You always think it may be the last time and one day you will be right).

Brooks says it’s true that “all the clocks do not stop” when a loved one dies. “No one silences the phone. The dogs continue to bark, the pianos to play,” she writes.

She did her best to get on with things. Yet three years on from Horwitz’s death she felt stuck in sorrow, “pretending to be normal, when I didn’t feel normal at all”.

She flew to Flinders Island – a wild and beautiful place, off the coast of Tasmania – determined to stay as long as she needed, to take back “something our culture has stopped freely giving: the right to grieve”.

She took with her some of Horwitz’s journals, including the one he was writing in when they met, all those years ago.

It was a gift to see, again, how much she meant to him.

“It’s a kind of a pale shadow of having him here, but I’ll take what I can get,” she says.

She stayed alone and allowed herself to truly feel every emotion: anger, loss, sorrow.

Love.

In time, she wrote her own story, which addresses the confusing, painful days (and years) of early widowhood. Memorial Days is a handsome hardback, with a golden cover. Readers are likely to include other women (and men) still trying to push through the thick soup of trauma.

She doesn’t want to presume that she can help them.

“I am usually thinking about the relationship between me, as the writer, and the readers,” she says. “But this book was just something I had to do … I had to write it.”

Brooks will be a guest of the Brisbane Writers Festival on Tuesday. She understands that some people will want to share their own stories of grief and she will have to talk about Horwitz.

How prepared does she feel?

“Not super prepared,” she says. “But I recently did the first public event in San Francisco, and we brought Tony into the conversation. And because he was funny, it can be light, and not a dirge, because I have no interest in going into that head space entirely … and I would like to hear from people who knew Tony because it does help to remember his humour.”

It helps to smile, in other words. To smile, and fondly remember, as on we all go.

Geraldine Brooks will be in conversation with fellow writer Susan Johnson for a Brisbane Writers Festival event at the Brisbane Powerhouse on Tuesday, February 25; tickets online. Memorial Days is published by Hachette.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout