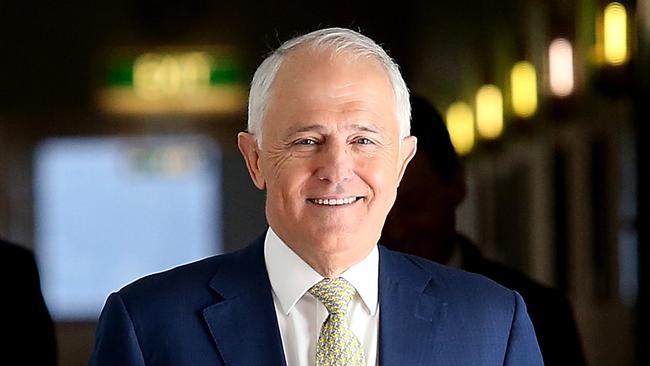

Liberal Party 75 years: celebrate the progressive, says Malcolm Turnbull

Former prime minister Malcolm Turnbull urges Liberals not to be seduced by reactionary populism.

Malcolm Turnbull sees the 75th anniversary of the Liberal Party as an opportunity to celebrate it being “genuinely progressive” rather than conventionally “conservative”, which has enabled it to lay the building blocks of “the Australian achievement” postwar.

In his first major interview since stepping down as prime minister last year, Turnbull reflected on the Liberal Party’s history and philosophy, his term as prime minister and the policy issues with which he grappled, and cautioned against the party being seduced by a populist reactionary brand of conservatism prevalent abroad.

“(Robert) Menzies was establishing the Liberal Party at a time when people were rejecting both the authoritarianism of the left and the right, both communism and fascism, and the conventional laissez-faire capitalism that people did not think served them well during the years leading up to the war,” Turnbull, 64, tells The Australian. “Menzies was looking to chart a way that was genuinely progressive and wasn’t one that was seen to be a sort of conventional conservative party beholden to big vested interests.”

Turnbull summarises the party’s central tenets: “The Liberal Party believes that government’s job is to enable you to do your best whereas Labor, in its DNA, if you like, believes that government’s role is to tell you what’s best.”

Liberal Party 75th Anniversary: Blame denialists for high power bills: Turnbull | Inquirer: Tony Abbott, the accidental PM | Praise the Libs for progress: Howard | The centre-right’s date with destiny

Turnbull explains that he sought to lead the party in the same way as Menzies, who drove the founding of the party at twin conferences in late 1944.

Turnbull’s conception of the party, and how he articulates its purpose and philosophy, is different to that of his prime ministerial predecessors, Tony Abbott and John Howard.

“I ran a very progressive and reforming government but most importantly I got a lot done, and that is because it is one thing to be in office, it’s another thing to actually do something with it,” he says.

Turnbull says he sees himself as a “progressive” and “reformist” Liberal leader and has described the party as a centrist, middle-of-the-road and moderate party.

But does he also see himself as a “conservative”?

“I am conservative but the difficulty is that the term has been completely debauched,” he responds. “Most of the people who claim to be conservatives nowadays would be better off described as reactionaries or populists. I mean, conservatives respect tradition (and) they build upon existing tradition as they embrace change.

“A lot of the people that talk about conservatism would not know the difference between Edmund Burke and Tony Burke. So, it is a term that is thrown around a lot. I mean, Donald Trump, for example, is not a conservative. Whatever he is, he is not a conservative.

“The space that people have often identified with a conservative approach is increasingly being occupied by populists who are, whether you describe them as reactionaries or authoritarian populists I’m not sure, but there is certainly nothing conservative about it.”

Turnbull is one of three people who have led the party twice — from 2008 to 2009 and from 2015 to 2018 — along with Andrew Peacock (1983-85; 1989-90) and Howard (1985-89; 1995-2007). He is the Liberal Party’s eighth prime minister and served for almost three years in the job.

“I got much more done as PM than I thought I would be able to, given the political circumstances of the time,” Turnbull reflects. “I was very focused on economic growth, economic success for Australia and Australians, very focused on free trade, very focused on innovation, but also determined to ensure that people enjoyed freedom in the social realm so that’s why I went to such lengths to ensure gay marriage was legalised.”

Turnbull nominates other achievements: personal taxation reform, Snowy Hydro 2.0, improving battery storage capacity, a new schools funding deal, developing a new approach to city planning, a new defence industry plan and keeping the Trans-Pacific Partnership alive. He convinced Trump not to impose tariffs or quotas on Australian steel or aluminium, and persuaded him to maintain a refugee swap deal.

Both times Turnbull exited the Liberal leadership there were internal divisions between moderates and conservatives with climate change and energy policy being a lightning rod for dissent.

His principal regret will come as no surprise: “I wish we could have resolved the energy situation,” he says.

Turnbull’s approach to climate change, he insists, does not reflect a dividing line between liberalism and conservatism, or change and tradition, but is simply a matter of reason, logic and, above all, science. True conservatives, he suggests, would embrace the need to address the warming of the planet. This view, though passionately held, will not endear him to some of his former colleagues.

“Conservatives are practical,” he argues. “There is nothing conservative, for example, (in) denying the science of climate change. That’s not a conservative position. That is just, well, that is just denying reality. You might as well deny gravity.”

Turnbull does not hold back in what he sees as a major failing of government, including his own, on developing a national energy policy that would reduce emissions and provide reliability in the future supply of power. Australia’s greenhouse gas emissions increased by 3.1 million tonnes of carbon, or 0.6 per cent, in the year to March. Australia’s total emissions have increased, year-on-year, for the past five years. The government insists, however, that we are on track to meet our Paris commitments. “The failure to have a coherent national energy policy is a major problem but it is founded on this rock of climate denialism inside the Liberal Party and inside the media, including by the newspaper you work for,” Turnbull says.

“We are paying higher prices for electricity than we should and we are having (more) emissions than we should, so it is a lose-lose, and if you talk to anybody in industry, the energy sector, they will confirm what I just said to you.”

Turnbull knows what needs to be done — and notes the comprehensive climate policies pursued by the British Conservative Party led by David Cameron, Theresa May and Boris Johnson — and who to blame.

“We (need to) have an effective set of rules to govern our energy market and ensure a low cost and stable transition from burning fossil fuels to renewable energy,” he argues. In other words, the National Energy Guarantee and related policies championed by his government that facilitated a mix of legacy generators and renewable energy sources meeting clear reliability and emissions reduction obligations.

“The Liberal Party has just proved itself incapable of dealing with the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions in any sort of systematic way … that has been a serious failing but the consequence, as I said, is without question that we are paying higher prices for electricity and having higher emissions.”

Working as a journalist, lawyer and businessman, and having been the nation’s pre-eminent republican, seems like good training for politics. Turnbull is coy, though, about when he first aspired to be prime minister. He joined the Liberal Party in 1973. The claim that Turnbull considered being a Labor MP is nonsense, he says.

“I was often encouraged to join the Labor Party,” he explains. “The most serious approach was from Paul Keating during the republican campaign and Paul was quite insistent.” Turnbull says he did not think he would be comfortable in the party or the party would be comfortable with him.

Turnbull was elected to parliament in October 2004 and served as environment and water minister (2007) in the Howard government and communications minister (2013-15) in the Abbott government. Turnbull says he admired how Howard, unlike Abbott, practised “traditional cabinet government” and he returned to this during his prime ministership. So, did he always harbour an ambition to become prime minister?

“When I went into parliament, John Howard was prime minister and everybody expected, I think without exception, that Peter Costello would succeed him,” he recalls. “Recognising that Peter is a few years younger than me, the circumstances in which I would become leader seemed unlikely.”

When Howard lost his seat in November 2007 and Costello declined to nominate for the Liberal leadership (and later quit parliament), Turnbull contested a ballot against Brendan Nelson and lost by 45-42 votes.

Nelson’s leadership came under sustained pressure as he struggled in the polls and failed to clearly articulate a policy on climate change. Turnbull challenged and defeated Nelson in a leadership ballot in September 2008, winning by 45-41 votes. But a year later, as Turnbull’s leadership came undone on climate change, he lost a leadership ballot to Abbott by one vote. Abbott led the Liberals back to power. Following an “empty chair” spill motion against Abbott, Turnbull returned to the leadership and became prime minister in September 2015.

Turnbull believes he was given an exceedingly difficult time by Abbott’s undermining during his prime ministership.

“I’d made my mind up a long time ago that when I ceased to be prime minister (that) I would cease to be an MP,” Turnbull says. “Having former leaders, you know, rattling around the parliament has not been a happy experience.” The long-running Abbott-Turnbull feud has echoes of the Peacock-Howard rivalry in the 1980s. It ended only when one, or both, left parliament.

Reflecting on the Liberals’ 75th anniversary, Turnbull praises the party for being a “grassroots political movement” that represents all Australians rather than being the “political wing of the trade union movement” as Labor is. The Liberal Party is tied to no vested interests. But he worries that the membership is not as representative of the community as it once was and is not attracting the diversity of candidates it once did.

Turnbull will not reflect on losing the Liberal leadership and resigning as prime minister. This will be addressed in his forthcoming memoir. He can claim several notable achievements as prime minister. While he was not divisive, like his predecessor, he disappointed many in his party and the electorate who hoped for more.

His leadership never really recovered from the narrow election victory in July 2016. Turnbull’s critique of Abbott for “losing” so many Newspolls came back to haunt him as Bill Shorten’s Labor enjoyed a long lead in the polls.

He was undermined by some within his own ranks. Turnbull did, however, see off the man who wanted his job, Peter Dutton, with a series of clever tactical manoeuvres as his authority drained.

Julie Bishop served as deputy leader of the Liberal Party (2007-18) under three leaders. Turnbull is effusive in his praise of her. “She is eloquent, she is persuasive, she is incredibly hard working and I could not have asked for a more loyal or capable deputy,” he says.

He adds that Bishop would have made a great prime minister had the Liberal Party chosen her as his successor. “She certainly would have been very capable of doing it,” he says. “Yes, I certainly would have welcomed that … she certainly had the capacity to lead the party.”

There are some in the Liberal Party who believe that Turnbull was too “leftish” — his word — and led a “Labor-lite” government. They want to delegitimise his time as Liberal leader. This is a mistake. Turnbull, like all leaders, is a custodian of the party’s history and he should be respected as such.

Turnbull wants the Liberal Party to claim its place as a “change agent” that has been responsible for “massive reforms” that have shaped the economic and social development of Australia and its engagement with the world. But the party has not often told that story. “The Liberal Party is not as sentimental about its past and its history, and does not pay enough attention to its history,” Turnbull says. “There are hundreds of metres of shelves in libraries full of Labor history. How many are full of history of the Liberal Party? Very few.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout