Life and soul of the Liberal Party

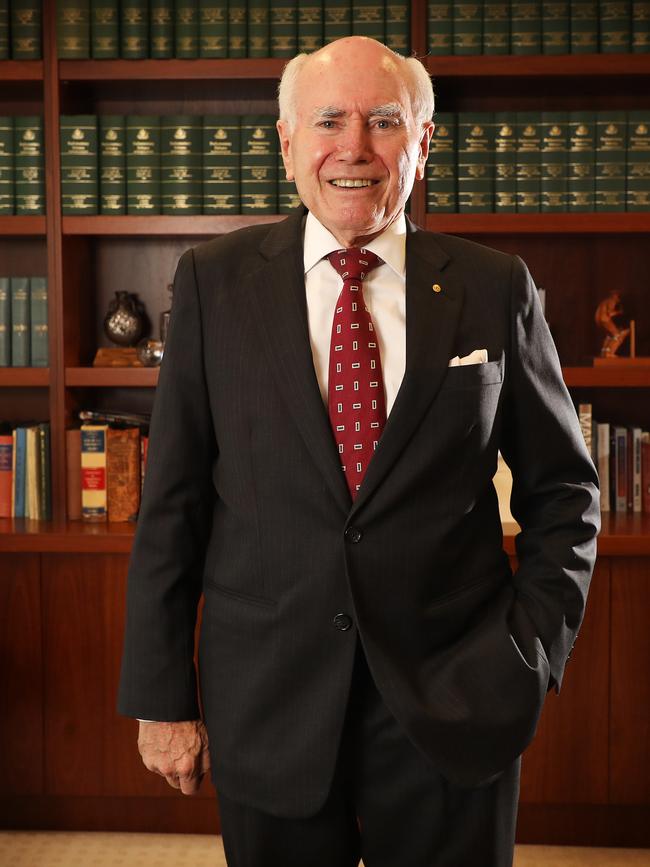

John Howard wants the Liberal Party to claim its place as the driver of national economic and social progress.

MORE: The centre-right’s date with destiny

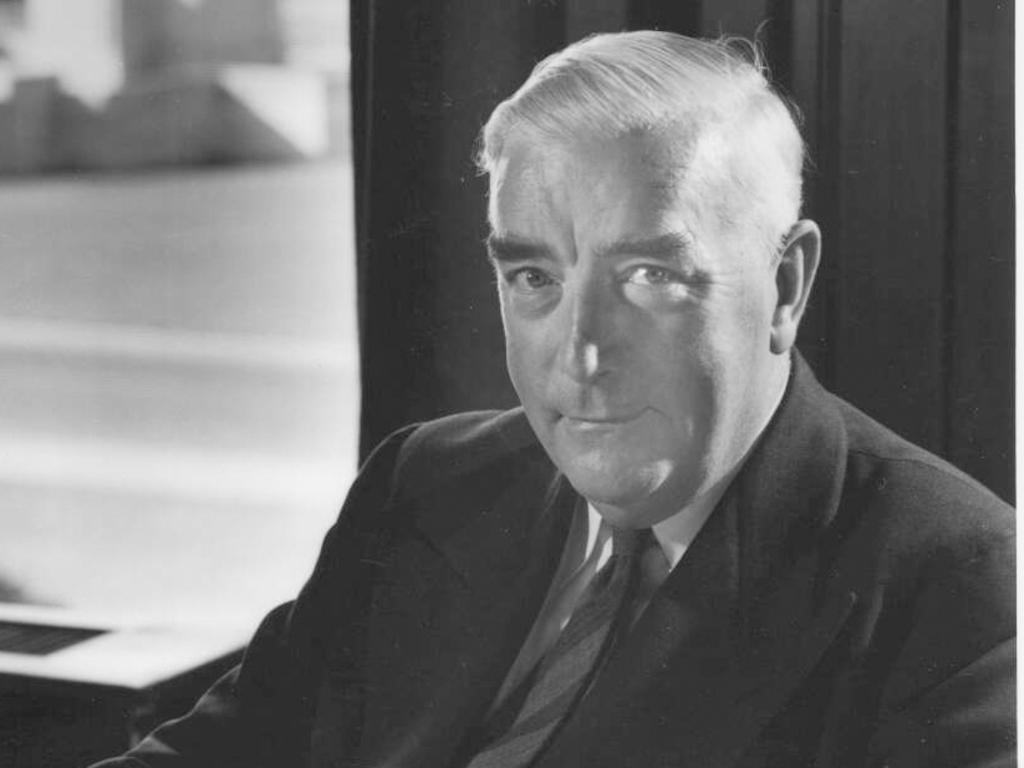

It is a bold claim — one that will be contested by Labor, formed in 1891 — but which Howard believes is supported by the contribution the Liberal Party has made to Australia since its formation at conferences convened by Robert Menzies in Canberra and Albury in 1944. The Liberal Party has governed nationally for almost two-thirds of its existence.

“The essential contribution the Liberal Party has made to Australia is progress, stability and laying the foundations of our middle-class character,” Howard, 80, tells The Weekend Australian.

“What is often not remarked is it is the party that oversaw the removal of negative aspects of our domestic, political and social discourse. It was under a Liberal government that the White Australia policy disappeared. It was under a Liberal government that a massive contribution was made to reducing the level of sectarianism in the Australian community. And it was under a Liberal government that the first opening up of Asia as a trading place for Australia occurred.”

Howard is referring to the dismantling of Australia’s racially based immigration program by Harold Holt’s government, the introduction of state aid for non-government schools by the Menzies government, and the signing of the Australia–Japan Commerce Agreement, also by the Menzies government.

To these achievements he adds “the dramatic growth in home ownership” and the rapid expansion of Australia’s middle class in the 1950s and 60s, the establishment of new universities where most students enjoyed scholarships, and “our most important security relationship” with the US being cemented with the ANZUS Treaty in 1951.

Howard, who led the party from 1985 to 1989 and from 1995 to 2007, is speaking exclusively to The Weekend Australian to mark the 75th anniversary of the formation of the Liberal Party of Australia. It is the first in a series of interviews with Liberal prime ministers that will continue next week.

While birthdays are a time for celebration, they are also an opportunity for reflection. Howard acknowledges the Liberal Party has “made errors” from time to time and there are always regrets and misjudgments, but insists “the balance sheet is a very positive one”.

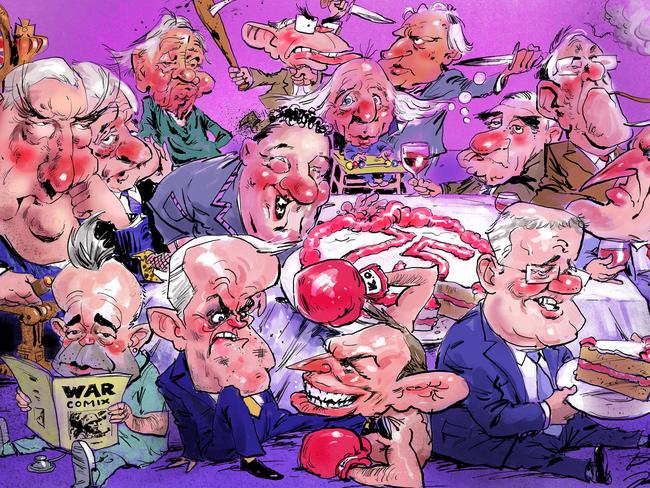

Nevertheless, in recent years the Liberal Party has been convulsed with leadership changes, differences about philosophy and policy, and calls to revitalise its membership and organisation. But it still managed to win an election this year and is in its third term of government — something Labor has achieved only once, and more than 30 years ago.

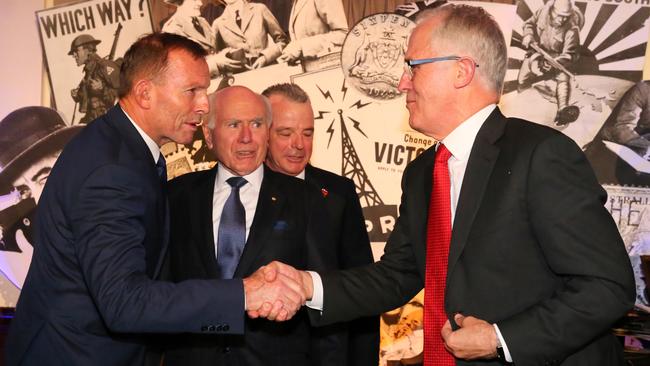

In his most candid interview since the election, Howard concedes that Tony Abbott and Malcolm Turnbull had “a people management issue”. The most important relationship that a Liberal leader has, Howard argues, is with those they immediately lead. Abbott and Turnbull are the only Liberal PMs to be felled by their partyroom since John Gorton in 1971.

“People management is critical,” Howard says. “I didn’t do it very well the first time I was leader of the Liberal Party; I was better the second time. This idea that you can reach out across the parliamentary system and draw all your authority from the people is true to a significant degree but if you don’t have a good relationship with the people that you immediately lead, you will get into trouble.”

Howard is generous to Abbott and Turnbull in his assessments of their leadership. He admires how Abbott, as opposition leader, reduced the Gillard government to a minority of seats. He says Abbott fulfilled his promise to “stop the boats”. He often found Turnbull’s speeches on economic and foreign policy to be well crafted and sensible.

He says Scott Morrison was “a miracle worker to win the last election” and praises his first year as Prime Minister. Howard concedes the leadership churn has been “traumatic” for the party and encourages MPs to continue to support Morrison and usher in a new period of stability.

“I rang Scott Morrison the night he became leader and said: ‘I will do anything I can to help you except barrack for Cronulla’,” Howard recalls. “I’ve been involved in, and seen, enough of leadership contests to understand they happen but we have been through a very strange period and I hope that that is behind us.”

Many of the differences between Abbott and Turnbull were ideologically driven as much as they were personality based. Howard says the key to unifying the Liberal Party is recognising that it is a custodian of both liberalism and conservatism. It is a lesson that must be perpetually learnt.

“It is very much a broad church,” Howard explains. “It is the trustee of both the classical liberal tradition and the conservative tradition. We are not wholly conservative or wholly classically liberal; we are a mixture of the two. And we are normally more successful when that is the prevailing sentiment.”

Some Liberal leaders, such as Menzies, Gorton and Malcolm Fraser, preferred to describe themselves as “liberal”. Howard and Abbott have used “conservative” to describe their personal political philosophy. Turnbull has described the Menzies tradition as “centrist” and “progressive”.

“There can never be a winner-takes-all approach to everything,” Howard says. “You are going to have differences and managing differences within a political party is a challenge, and it is a greater challenge now in some senses than it was in Menzies’ time.”

Howard is the only living Liberal PM to have met all of his 13 predecessors and successors who have led the party.

Like all Liberals, Howard puts Menzies on a pedestal. He met Menzies only once — at a cocktail party at the Lodge in 1964. (He was mixing drinks.) He especially admired Holt’s focus on Asia. And he formed “a more positive view” of Gorton, who “saw Australia as a single unit” at a time when “economic parochialism” was prevalent. He saw a lot of Billy McMahon and assisted him during the 1972 election campaign.

When Howard was elected to parliament in May 1974, Billy Snedden was Liberal leader. But he thought Fraser should lead the party. Howard supported a spill motion in November 1974 and then backed Fraser against Snedden in March 1975. Howard served as treasurer (1977-83) during the Fraser government. When Andrew Peacock challenged Fraser in April 1982, Howard stood by his prime minister.

“I thought Fraser was effective as an opposition leader and his early years as prime minister,” Howard recalls. “He became very critical of my government and I thought some of his criticisms were unreasonable, but there you go. He was a very strong, effective leader in his early years.”

It diminishes the Liberal Party’s historical memory that Gorton and Fraser resigned from the party. Gorton stood unsuccessfully against the party as an independent Senate candidate in December 1975. (He later returned to the fold.) Fraser became a biting critic of the party he led for eight years. John Hewson is routinely at odds with the party today. “I think they probably, in some cases, do themselves more harm with their criticisms,” Howard says.

Howard says he did not have a strong ambition to lead the party from a young age. His priority was to secure preselection for a safe seat, win that seat and then join the frontbench. “I can’t say that I saw myself as a likely leader the moment I entered parliament,” he reveals.

But Howard had a rapid rise through Liberal ranks. In only his second year in parliament, he became a minister in the Fraser government. He became deputy leader in April 1982. He lost a leadership ballot to Peacock in March 1983. The long-running Peacock-Howard feud continued through the 80s. When Peacock tried to dump Howard as deputy leader in September 1985 and failed, Howard unexpectedly emerged as leader when Peacock suddenly resigned.

Howard’s first period of leadership was not a happy time. The Liberals were divided between “wets” and “dries” on policy issues. He labels the quixotic bid by Queensland premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen to become prime minister and the resulting split in the Coalition as a time of “civil war”. It was the most difficult period during his time in parliament.

Howard defeated Peacock when his leadership was challenged after losing the July 1987 election to Bob Hawke’s Labor. In May 1989 Howard was the victim of a surprise coup by Peacock, who reclaimed the leadership. It looked as if Howard’s chances of becoming prime minister were finished. “That would be like Lazarus with a triple bypass,” he said.

But Howard is Australia’s greatest political survivor. He failed to dislodge Hewson from the leadership after the disastrous March 1993 election. In May 1994, the party made Alexander Downer leader. Then, after Downer’s leadership collapsed, Howard returned, Lazarus-like, to the leadership unopposed in January 1995. He led the Liberals back to power in March 1996.

Howard has identified economic and budget management, taxation reform, border protection and waterfront reform high among his achievements as prime minister. He especially nominates gun law reform, assisting East Timor’s transition to independence, developing a closer relationship with Indonesia, and balancing relations with the US and China. But in this interview, he will not be drawn on regrets. “I obviously made some mistakes,” Howard concedes. “(But) I’m not into self-flagellation.” Pushed on the decision to commit Australian forces to disarm Iraq in March 2003, Howard acknowledges it was “very unpopular” but not that it was a misjudgment in hindsight.

Howard praises his long-term deputy, Peter Costello (1994-2007), and the four Nationals leaders with whom he worked closely: Ian Sinclair (1984-89), Tim Fischer (1990-99) John Anderson (1999-2005) and Mark Vaile (2005-07). These relationships were indispensable, he says, to leading a government of longevity and stability.

As Howard reflects on the Liberal Party today, he is concerned about declining membership and formalised factions, which did not exist when he was leader. The party had about 200,000 members in the 50s; it is about 50,000 (including the Liberal National Party in Queensland) today. The result is that the party is less representative of the electorate than it once was and is finding it difficult to attract candidates with a diversity of life and work experience.

“Party membership decline is an undoubted fact (and) it does bother me,” he says. “You have this phenomenon in political parties all around the world where the active membership is unrepresentative of the generality of the people who vote for them.”

When Howard stood for preselection for the federal seat of Berowra ahead of the December 1972 election, there were 33 candidates. When he won preselection for Bennelong for the May 1974 election, there were 24 candidates. Howard says this would not happen today.

“The party is too heavily factionalised and people feel they are wasting their time in nominating because the factions have got it sewn up and anybody who pretends otherwise is deluding themselves,” he says.

Howard supports more democracy within the Liberal Party and says the introduction of plebiscites in NSW should help to break down the influence of factions over time. “I’m in favour of capable party activists getting preselection — I was one myself — and many of them end up making a big contribution, but you’ve also got to allow for the talented outsider,” he says. “It’s quite hard to get talented outsiders if you have a tight factional system.”

Howard would like the Liberal Party to do more to tell its own story. As the author of several books and having presented a documentary on Menzies, Howard has done his share. The history of the Liberal Party is not just a partisan story but one that, like the history of the Labor Party, is inexorably woven into the story of Australia.

“I don’t think the Liberal Party has done enough to promote its own history,” Howard says. “I think the Labor Party has run away with the narratives about Australian history. But we are gaining ground on them.”

John Howard wants the Liberal Party, on its 75th anniversary, to claim its place as the driver of national economic and social progress, and as an innovator in foreign relations, which has given Australia decades of prosperity and stability, and shaped our national character, aspirations and ambitions.