Josh Frydenberg kicks the reform can down the road

I am starting to think that Frydenberg has more in common with John Howard than Scott Morrison ever has.

The Treasurer put his stamp on that budget, spruiking the “back in black” mantra and fashioning the books, such that the Coalition could sell itself to the public as the side of politics that repaired the finances. It was a powerful sell.

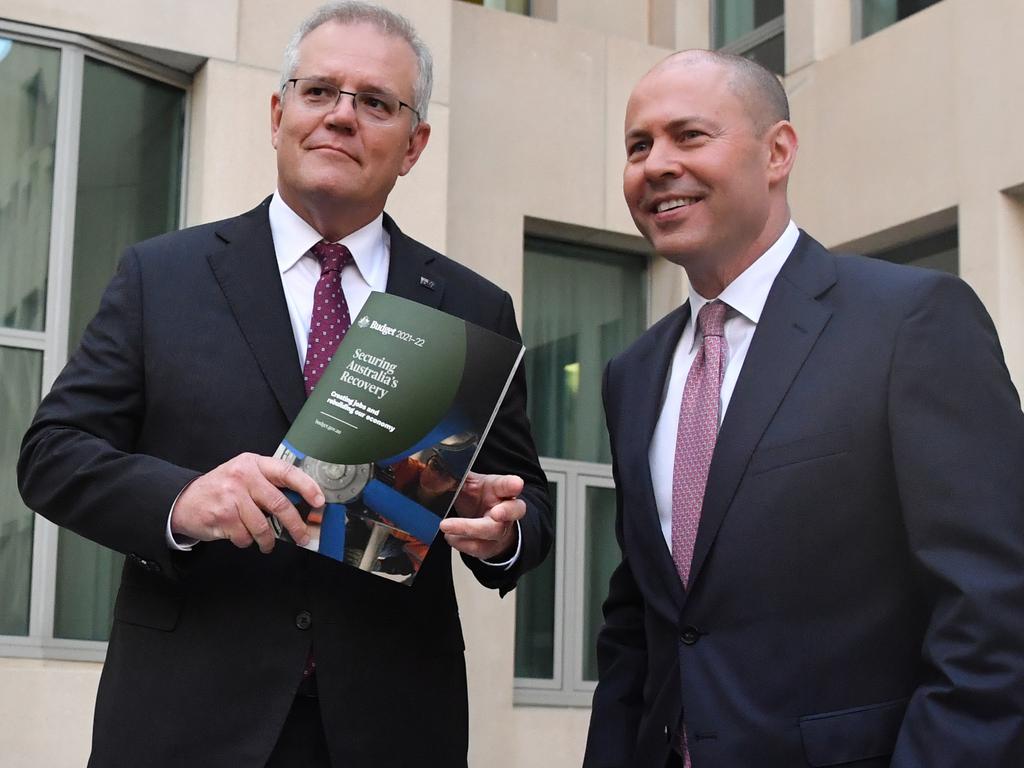

Facts don’t always see eye-to-eye with political spin. In government the Coalition at that time already had doubled the debt it inherited from Labor in 2013 and “back in black” would turn out to be a mirage. But there is no denying the role Frydenberg played in that election win, even if the Prime Minister rightly gets the lion’s share of the credit.

The hit job on Bill Shorten’s economic credibility to lead the country was effective politicking.

Fast forward to now and a similar outcome might be in the offing after Tuesday night’s budget, even if the complexion of the comparison is very different. Frydenberg is seeking to paint the Coalition as prepared to junk ideological zeal for the practicalities of addressing voter needs. But he also has framed the budget as important to support economic growth to fight rising debt. Then there is the goal of full employment, with which even Labor concurs.

But Tuesday night certainly wasn’t all good news.

Wall-to-wall deficits across the forward estimates. Record debt in the current financial year, forecast to come in at a tick under $161bn. National debt surging past $1.2 trillion. These numbers will be a burden for future generations, certainly if interest rates move north as they inevitably must one day. While the Coalition has clearly overcome its fears about a “debt and deficit disaster” (Joe Hockey’s words before the 2013 election), the debt-funded spending is repairing long-neglected policy areas such as aged care, childcare and the National Disability Insurance Scheme. And even though I was surprised more money wasn’t spent on initiatives for women, there is cash going into programs to address domestic violence and workplace harassment too, just not enough.

Usually a conservative government finds itself playing the role of the bad guy when it comes to hand outs, crimping spending with the aim of getting the structural deficit under control. Not any more.

Frydenberg has jettisoned that mantra unapologetically and has replaced it with largesse. His critics want to focus on the backflip and hypocrisy, which is an issue. But it isn’t the issue for voters, who simply want to be looked after by their government. Too often political insiders focus on the manoeuvring rather than the outcome of said manoeuvring.

Labor is left to criticise the spending priorities from the sidelines while lamenting waste along the way. Or it can pivot right and cast itself as the safer economic managers by embracing fiscal conservatism. Anthony Albanese’s budget reply speech suggests he’ll try to do all of that, which risks casting the Opposition Leader as all things to all people. We will see. It isn’t an easy position for Labor to be in.

But the most important outcome of the latest release of finance numbers alongside the political responses is that the reform can continues to be kicked down the road.

Australians need to have a conversation about what we expect of governments. Do we see the role of government as more interventionist in our lives than has been the case in the past? Is the safety net that modern governments have a duty to provide not cast wide enough? This is where the conversation needs to go. I suspect most voters do want more from government, which explains why the money flowing to a greater extent than it has in the past is tolerable.

But if such a brand of social liberalism is the ethos we want, everyone has to get realistic about what it takes to provide that. Debt is funding recurrent expenditure, putting the budget in structural deficit. With more expected of government alongside challenges such as ageing and reduced migration post-pandemic, our politicians need to debate what has to change to accommodate community expectations.

Right now extra needs are being funded by extra debt. And with limited buyers of Australian government bonds on the international market the Reserve Bank is snaffling them up, which essentially means it’s just printing money. Eventually this will have to put upward pressure on inflation and interest rates, which in turn makes paying debt interest more expensive. And, by the way, the AAA credit rating — while confirmed — has been put on a watch list. If we lose it, that also sends interest rates north.

If we want more from government, we need government to embrace ways of funding those additional things. That means higher taxes, but it’s never that simple. Putting taxes up can stifle economic growth. Enter tax reform. We need higher taxes to fund higher recurrent spending, but new taxes need to be designed so they don’t become counter-productive and halt the expansion of the economic pie.

You get that outcome only with sweeping tax reform, but there’s no appetite for that, certainly not on the eve of an election at which a long-term government is seeking a fourth term. And it won’t be encouraged by an opposition burnt at the previous election that went big with reform ideas and lost.

To be fair to Frydenberg there is a lot more in the details of the budget than gets widely reported when it comes to rejigging taxes to complement economic growth. But that’s still not the equivalent of major reform.

I am starting to think that Frydenberg has more in common with John Howard than Morrison ever has. Morrison is perhaps more comparable to Malcolm Fraser, even if their compassionate policy scripts are polar opposites. Fraser won elections and was a hero for doing so, but ultimately led a government that plunged the country into recession and accrued debt.

Howard was Fraser’s treasurer, so he shares that legacy. However, once unshackled from the Fraser years, Howard was able to spruik micro-economic reforms that should have happened under Fraser but didn’t.

The only problem was that Howard had to wait 13 long years to get back into government to start his prime ministership. That seems unlikely to happen again in the fast-paced environment of modern politics, even for Frydenberg, who is already approaching age 50.

Peter van Onselen is a professor of politics and public policy and the University of Western Australia and Griffith University.

People underestimate the importance of Josh Frydenberg’s first budget in helping the Coalition at the 2019 election, when Scott Morrison came from behind to win. The budget was brought forward to April to accommodate a May 18 election.