Budget 2021: Borrow and spend strategy to buy us time

Australia is being remade by disruptive forces and a pair of pushy Liberals who are resetting the fiscal rules of play.

Australia is being remade by disruptive forces accelerated by the pandemic and by a pair of pushy Liberals who, in reacting to the crisis with a spending splurge, are resetting the fiscal rules of play.

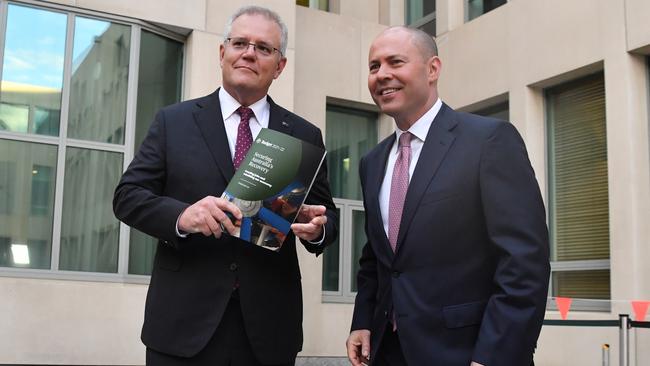

Scott Morrison and Josh Frydenberg are in a joint enterprise to steer the nation to safer waters, so that consumers will spend, businesses will hire, workers will feel secure, and a vast debt can be managed over time.

The budget may be a set of numbers, twisting from millions to billions and now even trillions, but it is simply a tool to set priorities. How you spend and what you tax can be modified and finessed by computer models, but they are controlled by people. So budgets are about values and if done properly they can fix mistakes we’ve made and deal with the world as it is.

Tuesday’s budget was an attempt to manage things in stages, with the most pressing issue to sustain the economic recovery, then lock in the gains. When life is looking more like it was before the crisis for finding and holding a job, the government will begin the huge task of changing the settings: from pumping out as much assistance as the economy can reasonably cope with to the politically fraught task of pulling some of that spending back to normal settings.

COVID-19 will leave us as a nation smaller, poorer, older and more indebted than we otherwise would have been. Treasury expects gross debt to hit $1.2 trillion by the end of its four-year forecasting period, or 50 per cent of gross domestic product, and to stay there until 2031. This is the highest level since World War II, according to the independent Parliamentary Budget Office. Before the Treasurer’s latest spending extravaganza, the PBO calculated it would take until 2055 before gross debt returned to its pre-pandemic level of 30 per cent of GDP.

Let’s get things straight. While our politics are hot and fast, in the mainstream there’s a vast overlap. Generally, the sound and fury are at the margins. We know where we’ve come from, perhaps the fog is lifting on the year ahead, but seeing the future, as it zigs and zags, requires a leap of imagination. Sensible policy can get us there in better shape than we’re in now, which will give us room to adjust to new circumstances.

More than ever, context matters and this budget is a creature of the moment. Our best minds can describe what’s happening right now, but they can’t be sure what trends will endure. Will work from home become the norm, with a growing preference for more spacious and detached homes on the urban fringe? Will the record population flows in favour of the regions, as country kids stay home and others seek cheaper housing away from Melbourne and Sydney, persist?

In October, with no proven vaccine for COVID-19, Treasury declared the pandemic “has the potential to permanently impact the way we live our lives”. For instance, “a greater shift to online consumer and business platform, reductions in retail and office space, and ongoing effects on global supply chains and trade flows” will present risks and opportunities. These trends are aided and abetted by digitalisation of services, such as education and health.

Seven months on, amid a troubled vaccine rollout at home and 800,000 new coronavirus infections a day, Treasury believes “the recovery in the Australian economy from the COVID-19 recession has continued to surpass expectations, having outperformed every major advanced economy in 2020”.

“Australia’s economic engine is roaring back to life,” the Treasurer declared in his budget speech. This time last year our economy was tanking, with a 7 per cent plunge in GDP in the June quarter. Over the second half of last year, the economy grew strongly with Treasury noting this was the first time on record when Australia has experienced two consecutive quarters of economic growth above 3 per cent. The unemployment rate, which Treasury initially thought could hit 15 per cent, peaked at 7.5 per cent last July, and has eased to 5.6 per cent.

It’s no secret why that happened. The Reserve Bank cut the official cash rate to 0.1 per cent and provided ultra-cheap loans to business. For its part, Canberra turned on the money hose, spraying $291bn in direct economic support to workers and companies. To put that in context, the stimulus alone is equivalent to one-in-seven dollars spent annually in the entire economy.

But wait, there’s more, such as the normal business of running a bureaucracy and delivering services. Canberra’s spending in the current financial year is 32 per cent of GDP. Sure, some of that was temporary, such as the JobKeeper payment that went to 3.8 million people and more than a million organisations; at $89bn, it was the largest single fiscal measure in Australia’s history. There’s been a step change in the federal footprint and spending will remain significantly higher than the long-term average for years to come.

Treasury expects growth of 4.25 per cent next financial year, with unemployment falling below 5 per cent by late 2022. The RBA’s forecasts are similar but its language is more upbeat. “The Australian economy is transitioning from recovery to expansion phase earlier and with more momentum than anticipated,” the RBA said in its statement on monetary policy ahead of the budget. “Along with favourable health outcomes and the removal of restrictions on activity, this snapback in activity has been supported by extraordinary fiscal and monetary support”.

While its outlook is positive, Treasury says “considerable risks remain”. “The continued economic recovery will rely on the effective containment of COVID-19 outbreaks both here and abroad and will be a key factor in the timing of the reopening of international borders, which could weigh on the outlook for the tourism and education sectors,” Treasury notes in the budget papers.

“Internationally, ongoing global trade tensions and the potential for further trade actions continue to pose risks to the outlook for Australian exports. More broadly, downside risks to the outlook for the global economy from ongoing outbreaks of the virus in major economies, including India, could have implications for Australia’s domestic economy.”

For some time, Australia will be closed to the world. This financial-year population growth will be the same near-zero rate as the cash rate, our slowest growth in more than 100 years. Then we’ll see population growth rates of 0.2 per cent and 0.8 per cent. Before the crisis, our population was growing by a rich-world-leading 1.5 per cent. The primary cause was “net overseas migration”, which is both permanent settlers and workers and students on temporary visas.

NOM was running at around 250,000 a year and was the main driver of economic growth. The Treasurer says the budget assumes this year there will be a net migrant outflow of 97,000, followed by a 77,000 loss next year. The gradual return of students and tourists will see the NOM returning to 235,000 people in 2024-25.

This pause to Big Australia provides an arena for an immigration policy reset. Last week, the RBA noted border closures and the population slowdown will actually lead to higher living standards and could spark wage rises in some regions and industries even though the economy will be smaller than previously expected.

Certainly, there are fewer people to share in the ongoing largesse of the state, from more spending on aged care, childcare, mental health, the vaccines program, housing, apprenticeships, women’s security, tax cuts for low and middle earners, investment incentives and infrastructure. It goes on, but you get the drift and the relentless money drip, drip, drip.

Frydenberg is getting an unexpected revenue windfall from personal income tax (more people in work) and company taxes (the miners and banks are getting fat profits) and he’s spending it pronto. The uplift in social infrastructure reflects changing political and policy realities. Royal commissions, no matter how worthy, cost money. First, to administer. Second, to respond. There is a multiplier effect, although advocates would argue it is never enough.

In a rich country, our aged-care system is scandalously inadequate, impersonal, overly complex and a relic of a time when a tiny proportion of people lived to a mighty age. Boomers and Gen Xers, too, demand more for their parents and, surprise-surprise, themselves. Will an additional $17.7bn over five years deliver a “generational change” to aged care?

You’d hope so, although there are doubts about the adequacy of the workforce skills to meet future needs. Ditto for childcare and disability services. There’s a burgeoning bureaucracy for sure, but what about the quality of care? Again, we shall see. The childcare spending addresses women’s workforce participation, something we’ll need to boost significantly if our borders stay closed and foreign workers are shut out.

Mental health, too, is an area of previous under-investment. But politicians are realising this is an issue for virtually all Australian families, at every stage of life. Spending here can pay immense dividends in community and workforce participation. Everyone wants more apprentices. Employers, those needing a roof after a bushfire, the family wanting to renovate so that Dad can work from home and contribute more to household tasks. Tradies are tomorrow’s enterprise class as well, so the parties fight to win them young. Reforms to TAFE last year and changes to skills recognition may be just as important as further wage subsidies to employ inexperienced workers.

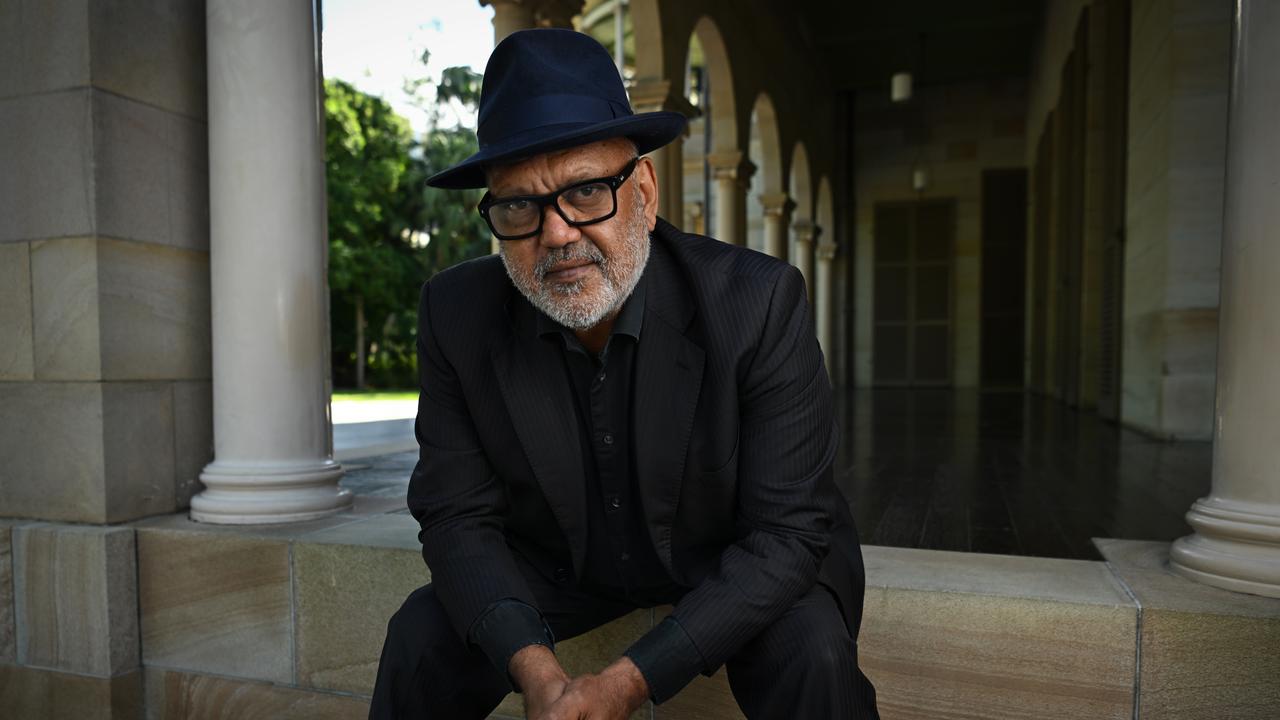

Hard infrastructure, where the touted federal pipeline is $110bn over a decade, must be rigorously assessed and properly priced. You can’t say that’s true for every road or dam and this area will be politicised for as long as there are marginal seats and loud men in hats. “Congestion-busting” and “nation-building” are always front of mind for pollsters. But you’d hope that in the next decade we can upgrade dispatchable energy storage for grid-scale renewables in line with net-zero emissions by 2050.

There is a recovery in business investment, but it was pretty crook before. An extension of the asset write-off scheme is “easy-as” at the expense of a bolder move like a cut in company tax or general investment allowance.

New utes are great, but we need more tools and platforms that turn ideas into jobs and profits. The new “patent box” tax regime for innovation, to keep manufacturing of medicines and high-end machinery onshore, is worthy. But let’s be wary of propping up industries with taxpayer subsidies under the umbrella of “sovereignty” and risk to supply chains. The numbers don’t stack up.

We haven’t broken the bank yet or given the credit watchers a stroke. When you take assets into account, “net debt” will peak at $980bn, or 40.9 per cent of GDP, in 2024-25. Several of our peers are in far worse shape. But money is cheap and interest payments are only 0.7 per cent of national income, a ratio that hasn’t changed in almost a decade even though the debt has grown fivefold.

Frydenberg talks a big game about a more dynamic economy and raising productivity, but that is not the focus of this budget. The underlying psychology remains fiscal survival mode, borrow and spend. Don’t slip back. It’s difficult, however, to see where the next spurt in living standards is going to come from. Indeed, there are warning signs from Treasury about our growth trajectory.

Sugar hits have got our economy back to the size it was pre-pandemic, but in a few years we’ll be stuck in the slow lane, due to a lower than anticipated population and very little action on improving industrial relations, cutting regulation and skilling up the workforce. In the recent past, our economy grew at an average of 2.75 per cent, and two decades ago it was way above that.

Now, Treasury tells us, over the medium term, potential GDP is projected to remain below its pre-pandemic “level”. But potential GDP “growth” is estimated to fall below 2 per cent a year. This is what you get in mature, ageing economies in Europe, not in a country that owns a continent and has high-income aspirations.

Have Morrison and Frydenberg, who look exhausted, got the right priorities? At best, this budget holds the line, buys jobs and growth and time, in an uncertain world. We are isolated, living on our inheritance about to hit our children with bill-shock. The pressure will be relentless, as we keep being hit by technological and climate change, global competition for talent and resources, geopolitical challenges and an ageing population, while testing the tolerance of creditors.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout