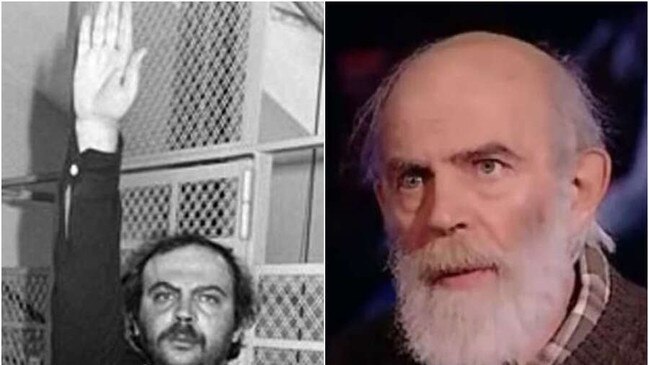

Italian fascist terrorist Pierluigi Concutelli murdered a lawyer — then claimed to be a political prisoner

After World War II, Italy went to war with itself for decades. Right in the thick of it was Pierluigi Concutelli. This is what a real fascist looks like.

OBITUARY

Pierluigi Concutelli,

neo-fascist terrorist, born Rome June 3, 1944. Died Rome, March 15, aged 78.

After the war, Italy went to war with itself for decades. There were communists, fascists, social democrats and then the ordinary Italians who just wanted the trains to run on time like they used to.

The myths of Benito Mussolini, including that of being the timetable tyrant, survived his execution and resonated in the hollow heads of thugs who wished for a return to the order they believed dictatorship delivered.

Quite why there were so many is probably only partly a mystery. The country’s north-south divide and its fractured education system were likely to blame as the urbanised north funded improved schooling and the more agricultural south lagged behind and was sometimes paralysed by mafia control of councils and government.

Substantial numbers of Italy’s communists drifted towards the centre in the 1960s and 1970s, but an educated thread of communists, as with the feared Red Brigades, still carried on an armed struggle in the name of Marxism – they kidnapped and assassinated former prime minister Aldo Moro in 1978. They then left his body in the boot of a car in central Rome not far from the Vatican.

Even today, Italian society sometimes presents itself as one of extremes in which 45 per cent oppose assistance for Ukraine, as measured by the country’s most read newspaper, Corriere della Sera, in a poll a few weeks back.

Pierluigi Concutelli was born into this often daunting, always fluid mix in which, it seems, nothing is done by half measure, the day before his birthplace and hometown, Rome, was liberated by American troops on June 4, 1944.

His parents were apolitical and just wished to get on with their lives after the brutal bedlam of the Mussolini decades. But his uncles had been fervent fascists and it is reported that he once saw a fading scrawl of pro-Mussolini graffiti on a railway bridge and decided at that moment to side with those Italians who believed in something they thought lost: a quest for virtue and order.

In any case, like most Europeans, he feared Soviet influence over a nation that has always had strong communist ties. In this era Italian thinking often expressed itself in murderous violence.

Looking at his writings it would appear he never thought of his family again and went on instead in search of the violence he thought would resolve what he saw as his country’s dilemma.

As a teenager he sought out the veterans of Mussolini’s Black Shirts, some of whom had taken part in the 1922 March on Rome. He then became part of Ordine Nuovo (New Order), an attempt to justify and replicate the National Fascist Party that had been banned after the war. In turn, New Order was proscribed in 1973, so Concutelli became a player in Ordine Nero (Black Order). Their hearts were that colour, their agenda urgent and he was their military commander.

Fascist anger had been at boiling point since 1969’s December 12 Piazza Fontana massacre – just one of five terror attacks that day there and in Rome. The bomb blast at a bank in Milan killed 17 and injured 87. It was the first episode in what would be known as a two-decade terror campaign – the Years of Lead.

Brilliant and brave rising lawyer Vittorio Occorsio was a prosecutor of those who had carried out this atrocity. (Some years later, and well before anyone else had any inkling of the Masonic P2 Lodge in Rome and its connections to Vatican finances, he was nobly and dangerously on the case.)

Concutelli, whose usual business was bank hold-ups and kidnap, decided Occorsio had humiliated his gang and had to die. He would arrange and carry out the assassination himself. At 8.30am on July 10, 1976, armed with an American-made Mac-10 submachine gun, he ambushed Occorsio’s Fiat 125 as the lawyer drove from home, killing him with 132 bullets. He also stole the prosecutor’s files, which contained the first details of P2. He fled, probably to Spain, for a time, but was arrested in Rome the following year, convicted of murder and sentenced to life in jail.

He told reporters he was a political prisoner. He never repented. Italy outlawed the death penalty in 1948 and many might have regretted that it was not applied to Concutelli.

While imprisoned, two jailed fascists were moved to Concutelli’s section, both suspected of being about to collaborate with the authorities: He strangled Ermano Buzzi with a shoelace in the exercise yard in 1981; a year later at the very same spot he strangled Carmine Palladino, also with a shoelace.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout