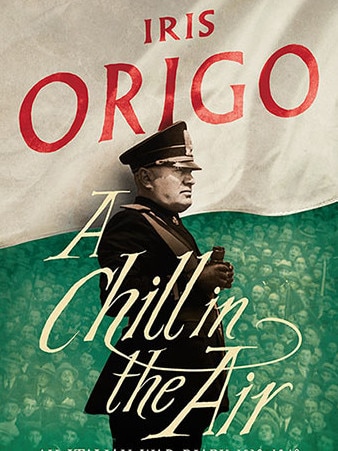

Poignant tale of how nation chose wrong and disastrous road

In an era of ‘fake news’ this diary written in 1939-40 about Benito Mussolini and Italy’s path to war offers chilling lessons.

You wouldn’t expect a diary written in 1939-40 about the uncertainty over whether Benito Mussolini would take Italy into World War II to be interesting. We know he did.

Yet Iris Origo’s A Chill in the Air is gripping because it records her efforts to see through the conflicting reports, the fake news, propaganda and rumours.

Her sources ranged from the BBC, French, German and Italian radio, peasant gossip and that of fascist and non-fascist aristocrats, to her godfather, William Phillips, the US ambassador to Italy.

It is important that initially she saw fascism as a genuine people’s revolution. In addition, fascist governmental subsidies aided her husband’s 3000ha estate near Siena.

Like Winston Churchill and many others outside Italy, Origo thought Mussolini would restrain Adolf Hitler. After all, public opinion was in favour of England and France, Italy’s World War I allies, so it seemed neutrality would be the likely and sensible decision.

But at the last moment all changed rapidly. One influential claim was that allying with Germany would enable Italy to reclaim Nice, formerly Nizza when it was Italian and Giuseppe Garibaldi’s birthplace, and thus complete the 19th-century Risorgimento.

After the German invasion of Belgium, in her diary Origo asked: “Is it possible to move a country to war, against its historical traditions, against the natural instincts and character of the majority of its inhabitants and very likely against its own interests?” She had to answer yes, it is possible, because, with German troops approaching Paris, Italy opportunistically sided with Germany, which was to prove disastrous.

This is relevant during today’s misinformation glut. In Italy, for instance, it is hard to understand whether the government wants to abandon the euro and leave the EU. Before the election last March, several key members of its present government had advocated these measures. They now say they have abandoned them but refuse to adopt the EU’s budget and cast it as an enemy. Some fear this is designed to claim later that Europe thwarted their reforms, hoping this would justify Italexit. That does not seem a sensible choice — but neither did allying with Germany in 1940.

A Chill in the Air is the prequel to Origo’s bestselling 1947 book War in the Val d’Orcia, which recounts how she and her husband risked their lives by aiding partisans and escaped Allied soldiers, who had been prisoners-of-war, and then led scores of peasants, old people and children through minefields to save them from Fascists. In that book, the goodies and baddies were clearly defined but the prequel shows the earlier situation was more complex, with those actively opposed to the regime a small minority.

Only now, seven decades after War in the Val D’Orcia, has A Chill in the Air been published, with a fine introduction by Lucy Hughes-Hallett and an afterword by Origo’s grandchild Katia Lysy, who recalls her nonna frequently organised picnics, charades, plays and read to her and six other grandchildren.

Origo, the daughter of a wealthy American who died when she was seven, was reared at a former villa of Cosimo Medici near Florence with Bernard Berenson, Henry James, Edith Wharton, Aldous Huxley and Somerset Maugham as visitors to the salon of her Anglo-Irish mother. Her father had wanted her to be free of nationalistic sentiments but she married Marquis Antonio Origo and became attached to Italy, as shown by her biographies of Italians such as poet Giacomo Leopardi.

In A Chill in the Air she rarely talks of herself or her family but provides significant scenes, for instance when, on June 10, 1940, the order arrived from the local Fascist office that all should listen to Mussolini’s broadcast from the balcony of Palazzo Venezia in central Rome. About 80 peasants and workmen plus supervisors and school teachers gathered in the front garden of the Origo villa to hear the amplified speech.

Mussolini announced Italy would enter the war to break the Anglo-French hold on the Mediterranean, champion the poor against the rich nations and the young against the decadent. The crowd in the square below Mussolini’s balcony was enthusiastic but not those in the villa garden who left silently. Iris and Antonio entered their home and looked at each other.

“This is it,” says Antonio, “I’m going to look at the wheat.”

Origo mentions her successful efforts to arrange for her mother and stepfather (essayist Percy Lubbock) to leave Florence before their arrest as enemy aliens but does not dwell on this as a possible problem also for herself.

Towards the end she also writes that she is about to give birth — the first mention of her pregnancy. The child, who she called Benedetta, now runs her mother’s estate La Foce (which means estuary or mouth of a river).

Desmond O’Grady is a Rome-based Australian journalist and author.

A Chill in the Air: An Italian War Diary 1939-40

By Iris Origo. Pushkin, 192pp, $19.99