Europe’s leap to the right has nothing to do with ‘fascism’

Swedes and Italians have elected traditionalists who, despite their considerable flaws, are the opposite of tyrants like Mussolini.

Fascism, it seems, is back, big time. The “entire philosophy” that underpins Donald Trump’s politics is “semi-fascism”, Joe Biden declared earlier this month. And descriptors such as “neo-fascist” and “post-fascist” have leapt off the front pages since the electoral successes of Jimmie Akesson’s Sweden Democrats and even more so of Giorgia Meloni’s Fratelli d’Italia.

It hardly needs to be said that those terms aren’t compliments; rather, like Vladimir Putin’s description of Volodymyr Zelensky as a “neo-Nazi”, their intention is to evoke horrors that we thought were long past.

But fascism – which came to power in Italy exactly a century ago, when the blackshirts’ “March on Rome” in October 1922 precipitated the formation of a government headed by Benito Mussolini – was a historical phenomenon, whose nature needs to be properly grasped if its contemporary relevance is to be accurately assessed.

The difficulties that involves are formidable. To begin with, while the names of most ideologies smack of their ultimate aim – with “socialism”, for example, indicating a preference for social control – that is not the case for “fascism”.

Rather, the term emerged from the Italian word “fascio”, meaning a grouping of like elements, which was widely used in the 19th century to describe militant, often clandestine, political movements.

It was because of that usage, rather than as a gesture to the ancient Roman authority symbol of the fasces (a bundle of wooden rods and an axe bound together by leather thongs), that the veterans who formed the “Fasci Italiani di Combattimento” (Italian combat units) in 1919 were referred to as “fascisti” and their political movement as “fascismo”.

The label was therefore largely uninformative; and to make matters worse, the fascists’ program underwent drastic change as the movement developed.

When Mussolini campaigned, entirely unsuccessfully, in the 1919 elections, he promised to introduce the eight-hour day, progressive taxation and universal male and female suffrage, while slashing public bureaucracy.

“We will never accept a dictatorship,” Mussolini then claimed, vaunting his commitment to the rule of law; but by 1921, when the movement became the National Fascist Party, its program had been completely altered – and it would continue to evolve during fascism’s two decades in power.

That it was, and became increasingly, authoritarian is beyond doubt. However, it is equally clear that the authoritarianism was a means to an ideological end, rather than simply a way of consolidating the party’s stranglehold.

At its heart was the conviction that fascism’s mission was to forge an entirely new Italy – and entirely new Italians. The new Italy was to be a revolutionary break with the country’s recent past: a past which, according to the fascists, had seen it marginalised in the carve-up of Africa, poorly done-by in the territorial settlements which followed the World War I, and undermined by fractious and unstable governments.

Nor would the fascists’ “new man” bear any resemblance to the Italians the regime had inherited, who were infused by a “hedonism” characteristic of the “senile bourgeoisie”; rather, fascism would create Italians whose vigour, vitality and virility would ensure Italy’s emergence as a global power.

Unswervingly devoted to “believing, obeying and fighting for” the Duce, these “modern barbarians” would fashion an Italian empire that rivalled those of antiquity.

It was that aspiration to comprehensively reshape an entire population which Italian fascism pioneered, in ways later imitated by both Stalinism and Nazism, as well as by modernising autocrats such as Kemal Ataturk.

Fascism, Mussolini proudly exclaimed, was “the greatest experiment” ever attempted in altering national character; the regime’s authoritarianism was the instrument by which the “anthropological revolution” was to be effected. And that anthropological emphasis, with the enormous weight it placed on genuine “Italianita” (Italianness), laid the foundations for the virulent racism and anti-Semitism of fascism’s later years.

However, achieving the fascists’ goal of transforming Italians required more than mere authoritarianism; it demanded totalitarianism – the extension of state control to every facet of private life and the disappearance of the borders between society and the state.

The term “totalitarianism” had been coined by one of Mussolini’s earliest opponents and victims, Giovanni Amendola, in 1923; by 1928, the grand old man of Italian socialism, Filippo Turati, could write of the “worldwide conflict between fascistic totalitarianism and liberal democracy”.

But the regime did not hesitate to embrace the concept, with its leading theorist, Giovanni Gentile, describing the “total state” as the tool for “correcting” Italians’ longstanding vices and breeding future generations worthy of the country’s “genius”.

All that sharply separates the fascists from today’s populists. Populism exalts the virtues of “the people”, and celebrates unmediated popular rule, which it compares to the corruption of the elite; Mussolini, in contrast, despised ordinary Italians, who – far from being given control over the polity – were to be permanently subjected, in a rigidly hierarchical society, to the party’s elite of “warriors, thinkers and men of action”.

The difference between fascism and conservatism is every bit as profound. Instead of preserving Italy’s cultural and social inheritance, which Mussolini regarded as “supine, hypocritical, and lacking the will to power”, the regime’s goal was to eradicate traditional values in the name of a return – enforced through the cult of violence – to the martial virtues of republican Rome.

It is therefore hard to see in what sense, if any, populists such as Trump or traditionalists such as Meloni are fascists; their flaws, no matter how considerable, have nothing to do with fascism’s project of revolutionising human nature through the complete subjection of society to the state.

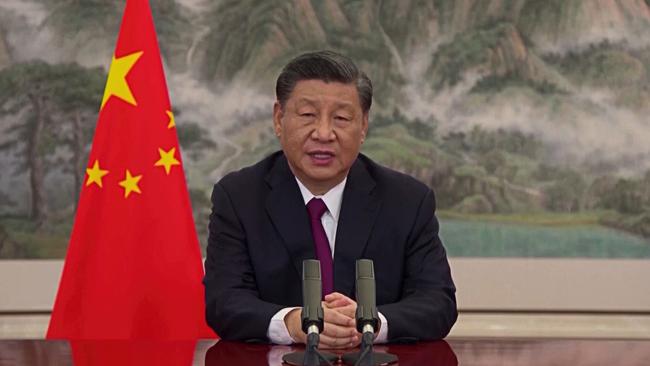

Rather, the most direct inheritor of the fascist legacy is Xi Jinping’s China, where the controls over individual thought and conduct that Soviet totalitarianism copied from Mussolini’s regime are being deployed, using increasingly sophisticated technologies, to mould the population to the Communist Party’s aspirations.

That doesn’t mean that we have nothing to fear closer to home. Fascism may be dead; but there are plenty of signs of a new totalitarianism.

Propelled by the rise of social media and given enormous impetus by the “Me Too” movement, the attacks on the distinction between the public sphere and private life – which is the foundation of a liberal society – have become all-pervasive.

At the same time, the resurgence, on both the left and the right, of a paranoid style of politics – which views every defeat as a conspiracy and every opponent as a mortal enemy – is trashing the legitimacy of democracy.

Ultimately, the West’s problem is not the return of yesterday’s ghastly errors; it is the emergence of new ones, which need to be understood, rather than reduced to slogans based on grievously inaccurate historical analogies. Until that is done, we will remain lost in a forest of confusion.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout