Don’t let bureaucracy dismantle voice to parliament recognition of First Australians

As a non-Indigenous Australian with a long-time commitment to Indigenous rights, I am a passionate advocate for recognition of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples in the Constitution.

There is no point in seeking constitutional recognition except in a form sought, desired and approved by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples themselves. That’s why I am a strong supporter of a constitutionally entrenched voice, that being the only mode of recognition acceptable to most of those Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander citizens who participated in the Uluru dialogues.

A successful referendum on this topic would be one that not only wins the necessary super majority of voters but one that also unites the country with an overwhelming and joyful vote for the recognition of the First Australians.

Process and wording matter if we are to get to Yes as resoundingly as possible. Given the lack of bipartisanship in the parliament, it is all the more necessary that the wording of the proposed constitutional change, in the words of the late Robert Ellicott KC, “contain no element of possible substantial confusion on legal or other grounds”.

Ever since the Uluru Statement from the Heart, it has been clear that there has been no point in pursuing any form of constitutional recognition unless it includes a voice to parliament. This was recommended in the final report of the Referendum Council in 2017. It might be noted that the council’s final report never mentioned “executive government”.

In my last article for Inquirer (25-6/2) I said, “The proposed change to the Constitution should be an accurate reflection of the recommendation made by the Referendum Council and as interpreted by Murray Gleeson – a member of that council and retired High Court chief justice, who spoke of a voice to parliament and not of a voice to parliament and executive government. Failing that condition, if the proposed change is to go beyond that, it should be approved by the parliament after consideration of a published legal opinion provided by the Solicitor-General.”

There is no doubt that the words proposed go well beyond the recommendation of the Referendum Council and as interpreted by Murray Gleeson in his 2019 speech. What’s proposed is a constitutionally entrenched voice with a constitutional entitlement to make representations to ministers and public servants as well as to parliament.

The voice will know what parliament is up to, and thus will be able to make representations. And the voice will know who the ministers are and will have a fair idea of what the ministers are up to within their portfolios.

BEST OF VOICE OPINION: All our commentators weigh in on the Indigenous voice to parliament

But if the voice is kept in the dark about what thousands of public servants are up to in making administrative decisions impacting Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons every day, then of course the voice will be able rightly to claim that it has been muffled or muted to the point of silence.

No one is seriously suggesting that it would be good enough just to leave it to the voice to discover if a public servant was about to make a decision, and that the voice’s ignorance of same would be a matter of supreme indifference to the courts.

If the voice has a constitutional entitlement to make representations to public servants, it will not be good enough to leave the voice in the dark, allowing them simply to make post facto complaints about administrative decisions that would be legally valid. The voice would need to know, ahead of time, what is going on in public service offices.

Representations to parliament considering new laws are one thing. Representations to ministers considering policies or practices, another. Representations to public servants making routine administrative decisions are an altogether different matter.

If the voice were simply a creation of statute, parliament could provide a statutory entitlement to make representations to public servants on administrative decisions relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander persons.

Such a wide-sweeping administrative law reform would be subject to legislative amendment should there be any unforeseen consequences or inordinate cost burdens bearing little substantive change to the quality of administrative decision making.

Executive government includes ministers and “other officers”, namely public servants. If parliament is wanting to maintain as much as possible of the proposed wording, I suggest the joint select committee consider using the familiar language of the Constitution and recommend that “the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice may make representations to the Parliament and the Ministers of State of the Commonwealth on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples”.

If there is a desire to include representations to commonwealth officers other than ministers, the parliamentary committee should seek advice from the Department of Social Services, the Department of Health and Aged Care, the Department of Employment and Workplace Relations, the Department of Education and the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet.

A comprehensive constitutional change to the system of public administration should be proposed to the Australian people only once competent advice has been provided to the parliamentary committee.

What is currently proposed is the creation of a constitutional entity (the voice) with a constitutional entitlement to make representations to public servants. The unresolved issue is determining the extent of the constitutional duty of public servants to ensure that the voice is adequately apprised of information to know that a decision is contemplated and of information sufficient to allow the voice to make a reasoned representation.

Professor Megan Davis (one of the drafters of the pre-Garma formula put to the 2018 joint committee) and her colleague Professor Gabrielle Appleby have outlined the scope of representations which might be made by the voice under the government’s proposed amendment:

“The voice will be able to speak to all parts of the government, including the cabinet, ministers, public servants, and independent statutory offices and agencies – such as the Reserve Bank, as well as a wide array of other agencies including, to name a few, Centrelink, the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority and the Ombudsman – on matters relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. This isn’t to be feared: as the Explanatory Memorandum says, the parliament will be able to set the procedure through which the voice’s representations are received, with the important caveat that the parliament won’t be able to stop the voice making those representations. It can’t shut the voice up.”

Downplaying the reach of the voice, some government members and sympathetic lawyers have suggested that the proposed amendment ensures that the parliament has full control over the voice.

Some have even suggested that parliament could restrict the class of representations or exclude certain public servants, departments or agencies from being required to receive representations or from being required to make any disclosure of intention to make a decision which might warrant a representation from the voice.

They have not refuted the Davis-Appleby position that “the parliament won’t be able to stop the voice making those representations”.

In his second reading speech, the Attorney-General said: “It will be a matter for the parliament to determine whether the executive government is under any obligation in relation to representations made by the voice … The constitutional amendment confers no power on the voice to prevent, delay or veto decisions of the parliament or the executive government.”

We need to ensure that the bill as amended complies with those statements.

The parliamentary committee should require that the Solicitor-General provide advice on whether the voice could delay decisions of the public service. The committee should insist that the government publish the Solicitor-General’s advice. His advice should address questions such as:

● Would the proposed amendment provide the voice with a constitutional entitlement to receive notice that a public servant was considering making an administrative decision relating to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples?

● Would the voice then have a constitutional entitlement to receive sufficient information from the public servant about the proposed decision so as to make an informed representation?

● What would constitute due consideration of any representation received?

● Would the public service have a constitutional duty to inform the voice that they were about to consider some policy options for submission to their minister when those options could relate to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples? And how early in the development of policy options would the constitutional duty to inform come into play?

● To what extent, if any, could any constitutional duty on the public service be modified or negated by parliament enacting a law under the proposed amendment which is specified to be “subject to this Constitution”?

● Which Commonwealth agencies would be required to receive representations from the voice?

● What limits might parliament set on representations from the voice to “independent statutory offices and agencies – such as the Reserve Bank, as well as a wide array of other agencies including, to name a few, Centrelink, the Great Barrier Marine Park Authority and the Ombudsman” (the Davis/Appleby list)?

Having heard from the Solicitor-General and departmental heads, the parliamentary committee might think it sensible to recommend that voice representations be confined to parliament and ministers of state.

The two political questions for the government and the referendum working group are: why not establish the voice in the Constitution with a constitutional entitlement to make representations only to parliament and ministers?

And, given the bureaucratic difficulties, why die in a ditch over a constitutional entitlement to make representations to public servants?

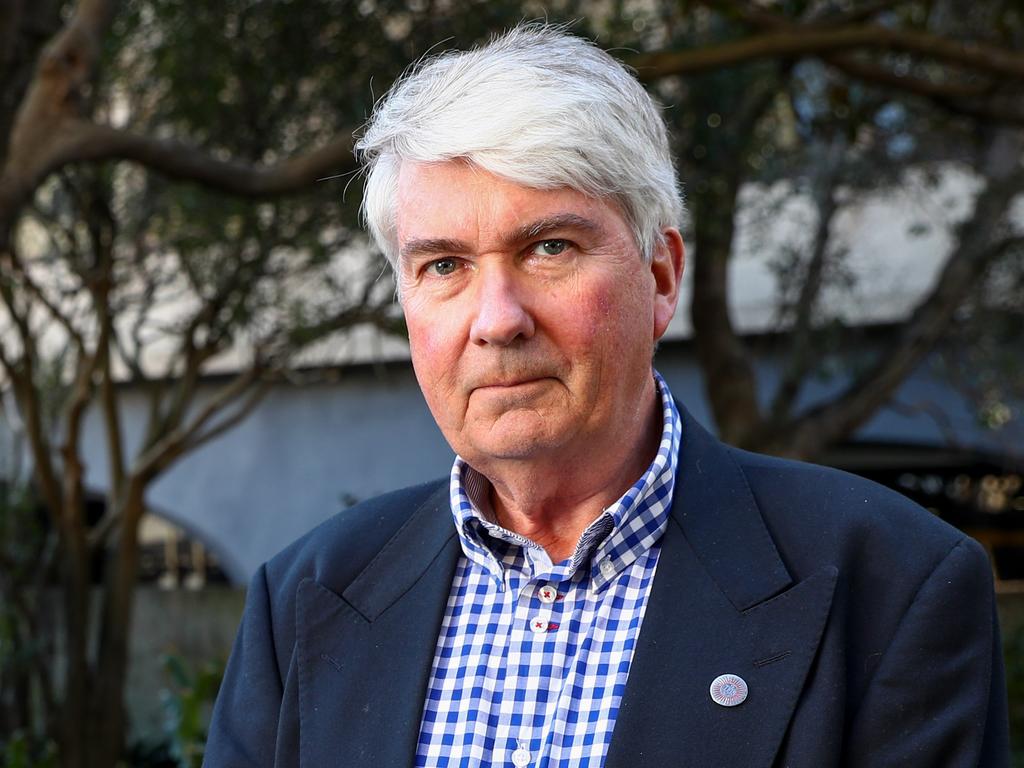

Frank Brennan’s latest book is An Indigenous Voice to Parliament: Considering a Constitutional Bridge (Garratt Publishing, 2023).

The government has finally set up a Joint Select Committee on the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Voice Referendum to receive public submissions on the proposed constitutional amendment on the voice.