MP Julian Leeser’s decision to quit frontbench over voice to parliament reinforces the spirit of Australian liberalism

To say that is not to endorse Leeser’s position. Nor is it to dispute John Hirst’s observation that Australians have come to believe that political parties are like “sporting teams whose members should all be kicking in the one direction”.

But that belief was never consistent with liberal principles, nor was it their progeny. Rather, the view that MPs should toe the party line was, as Hirst emphasised in his magnificent 2006 Allan Martin oration, one of Labor’s most pernicious contributions to Australia’s political life.

It developed in the late 1890s as the means by which the unions could tightly control their newly founded political wing; transformed in subsequent years into a dogma, Labor’s party discipline progressively robbed parliament of its role as a deliberative body, reducing it to a shrill confrontation between serried ranks of angry opponents.

Having thus poisoned the political climate, Labor had no difficulty convincing itself that unity was strength, which in some measure it undoubtedly was.

But the price of unity was a party culture that confused disagreement with heresy, castigating the expression of genuinely held differences as destructive at best, treacherous at worst.

By suffocating the scope for dissent on major issues, it provoked three disastrous splits – in 1916, 1931 and 1955 – that condemned Labor to languish in the wilderness for decades. And with those who left in each split being vilified as “rats”, it ensured, wrote Hirst, that “the social democratic cause in this country was led not so much by a party as by a tribe, fratricidal within and hostile to everyone without”.

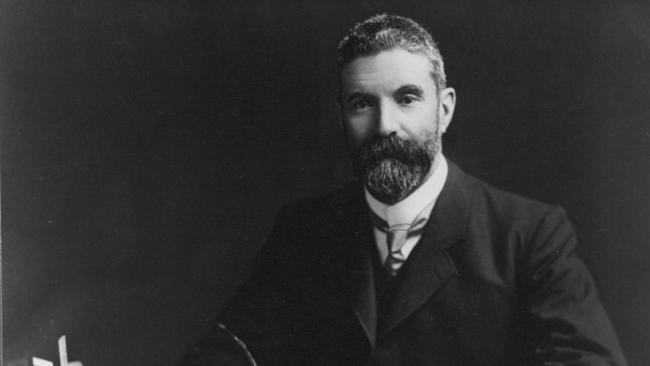

All that was bad enough. The tragedy, however, was that Labor’s opponents felt forced to mimic their rival’s approach, albeit never to the same extent. Alfred Deakin took the initial steps in that direction almost immediately after the anti-Labor forces fused in 1909; haltingly and unevenly, the trend became increasingly pronounced, particularly after the rise of television and then of the internet converted Australian politics into a 24-hour blood sport.

But the liberal conception of party, first articulated by Edmund Burke as parties emerged in the late 18th century, was altogether different. It is certainly true that Burke defined a political party as “a body of men united, for promoting by their joint endeavours the national interest, upon some particular principle in which they are all agreed”. Convinced that “When bad men combine, the good must associate, else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle”, no one put greater weight than Burke on political loyalty as a “virtue of the will” – that is, a virtue that makes it possible to pursue our projects and fulfil our obligations.

Burke understood that loyalty is not a fairweather value; it demands self-sacrifice and steadfastness when emotion, personal advantage and ambition would counsel otherwise. Yet Burke also understood that unlike personal fidelity, whose claims can be absolute, whether a virtue of the will is meritorious depends on the value of the objective it helps achieve: loyalty is commendable, blind obedience is not.

And because political loyalty is given to groups within which there are always differences, it is, of all the virtues, the one most subject to the pull of conflicting commitments and the clash of conflicting principles.

Its proper exercise therefore requires judgment and discrimination, along with honesty in explaining one’s choices. That is why Burke made it clear, in his famous speech to the electors of Bristol, that he owed them nothing but his “unbiased opinion, his mature judgment, his enlightened conscience”; and why he said that whenever the issue arose, he would always place above every other consideration the “one thing, and one thing only, which existed before this world, and which will survive the fabric of this world itself: justice”.

It was on that basis that he differed from his party on some of the most controversial questions of the day, relentlessly pursuing justice for Ireland and – the greatest cause of his life – for the people of India.

Those decisions were never self-serving; indeed, just as displays of loyalty that come at no personal cost manifest only its husk and not its inner substance, so the high costs Burke incurred for his choices mark them as acts of courage rather than betrayal. And he left no doubt that his was not a disavowal of his friends but a “loyal opposition” that – in seeking to preserve the principle for which he believed his party stood – was conservative in the best sense of the word.

Of course, none of that implies Leeser is right. On the contrary, having grappled during Passover with Deuteronomy’s command that “you shall remember that you were a slave in Egypt”, I am more convinced than ever that race is a blight to be erased from, rather than entrenched in, our Constitution. After all, what made the covenant at Mount Sinai so radical was that – unlike the other Middle Eastern religions of the time – it was addressed to and bound the whole of Israel, not a king, not the priests, not a ruling caste.

It was, in that sense, the beginning of the West’s long and winding journey, guided by the lodestar of political equality, to an ever expanding circle of citizenship in which each and every person would be vested with exactly the same fundamental rights and obligations. The Constitution is this nation’s covenant; it should embody that aspiration, not enshrine its abandonment.

But the spirit of liberalism is the spirit that knows that reasonable people can disagree. And it also teaches us that moral purity is the privilege of saints and hermits; everyday life demands compromises and even the acceptance of a degree of moral incoherence. How those compromises should be struck, as we seek an equilibrium between the different aspirations of differing groups of human beings, has always been, and will always be, contentious.

Working our way through that is the task ahead. Advocates of the voice will have their case to make; we will have ours. We may well end up disagreeing, but our arguments will be the better for it, hopefully to the benefit of the voting public.

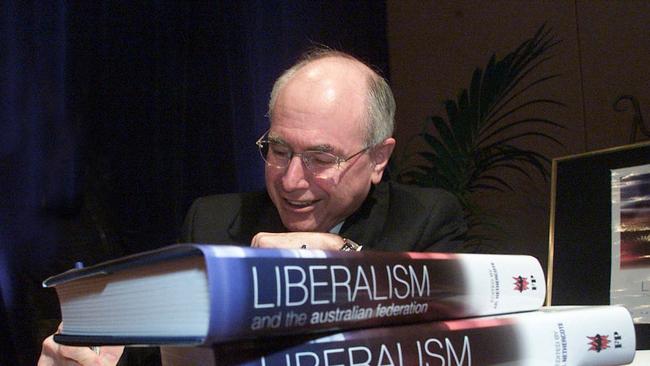

That is the enduring merit of independent thought, which is once again everywhere under attack. We need more of it, not less. By displaying it frankly and loyally, Julian Leeser has reminded us of why, for all of our differences, we can be proud of being liberals.

For all the discomfort it will cause in Liberal ranks, and all the gloating in Labor, Julian Leeser’s resignation from the frontbench on the issue of the Indigenous voice to parliament shows that the spirit of Australian liberalism is still alive.