Income poor but asset rich, welcome to Albo’s Boomer Nation

Labor is at risk of a revolt from Millennials and Gen Xers, who have suffered the most from the big slide in our living standards.

Still, we’re definitely not “in the toilet” as a Nationals gunslinger, who always shoots to kill, put it this week. More people in work than ever doesn’t smell like failure; the economy is in a trough but continues to grow. As Oscar Wilde observed, senator, “we are all in the gutter, but some of us are looking at the stars”.

On Thursday, Michele Bullock noted that even with a robust jobs market, headline inflation fell to 2.8 per cent in the September quarter, almost half its rate a year earlier because of government energy bill rebates.

“This is welcome relief for people feeling the pinch from the rise in the cost of living over the past two years – which is everyone, but particularly the more vulnerable people in our community,” said the Reserve Bank governor, who remains unconvinced inflation has been tamed.

The price of getting on, and staying on, the social escalator of home ownership and financial security is eating up record chunks of household budgets.

About half of a family’s income goes to servicing a median-sized mortgage. The consensus is the central bank won’t be lowering interest rates until just before or after the May due date for the next election.

Wages have not kept pace with prices, nor has national income grown in line with the population for the past six quarters, the longest slide in the 65 years these figures have been collected. Contrary to Coalition claims, however, the size of the economic pie has not shrunk during Labor’s term; it has grown by almost 3 per cent. But the population has increased by about 5 per cent or 1.3 million, mainly because of a record inflow of migrants.

But there’s another transition masked by the national averages, an intergenerational shake-up in which an ageing country becomes increasingly asset rich and income poor.

Welcome to Boomer Nation, where older Australians are wealthier and living it up, although no one has escaped the hit on purchasing power – especially those bringing up children. The value of our homes and financial assets, such as superannuation and shares, keeps rising.

Household wealth stands at $16.5 trillion, a figure difficult to comprehend as it’s equivalent to 6½ times the value of the goods and services we produce in a year.

It has grown by 55 per cent across the past five years; the value of residential land and dwellings has increased by 63 per cent, shares are up by 40 per cent and superannuation has grown by 26 per cent.

The bulk of this wealth is held by older Australians and it’s not dormant. It’s always Black Friday at the Bank of Mum & Dad, a subsidiary of the capital-depleted Nan & Pop Holdings, with extended trading hours across the festive season.

Across summer, Anthony Albanese will be trying to convince voters that Labor not only feels their pain but is doing something about it and that better days are ahead. The Coalition’s task may appear the easier one, all wrack and ruin, but who needs the Grinch around for Christmas when we have the Australian Test cricket team?

Labor came to power in May 2022, just weeks after the RBA began its cash-rate blitz. Since then the living costs of employee households (a different measure to the consumer price index, which does not include mortgage interest charges) have increased by 17 per cent compared with 11 per cent for self-funded retirees. The generational divide is essentially over borrowing costs, which have gone up by 150 per cent; most, although not all, retirees have paid off their homes – the ones they live in.

According to the latest CommBank iQ Cost of Living Insights analysis, “young Australians continue to feel the pinch more than any other age group”. Those aged 18 to 29 have cut back by about 2 per cent both essential and discretionary spending during the past year. Thirty-somethings, too, have tightened their belts by about half as much in both categories. By contrast, those in their 60s increased spending by 3.9 per cent and over-70s by 7.7 per cent, “underscoring the continued generational spending gap”, says the report, which draws on de-identified payments data from about seven million CBA customers.

“Lower petrol prices and government energy relief programs have eased the pressure on essential spending and July’s income tax cuts have increased take-home pay for many Australians,” CommBank iQ head of innovation and analytics Wade Tubman says. “However there continues to be a discrepancy between the spending power of older and younger Australians. In fact, we’ve seen those (aged) all the way up to 40 years old cut back on spending, highlighting the large swath of the population feeling cost-of-living pressure.”

Data provided to Inquirer by JWS Research reveals that twice as many Australians surveyed feel their own standard of living (a broader concept than concern over cost-of-living pressures) is good (41 per cent) compared with those who see their situation as poor (22 per cent).

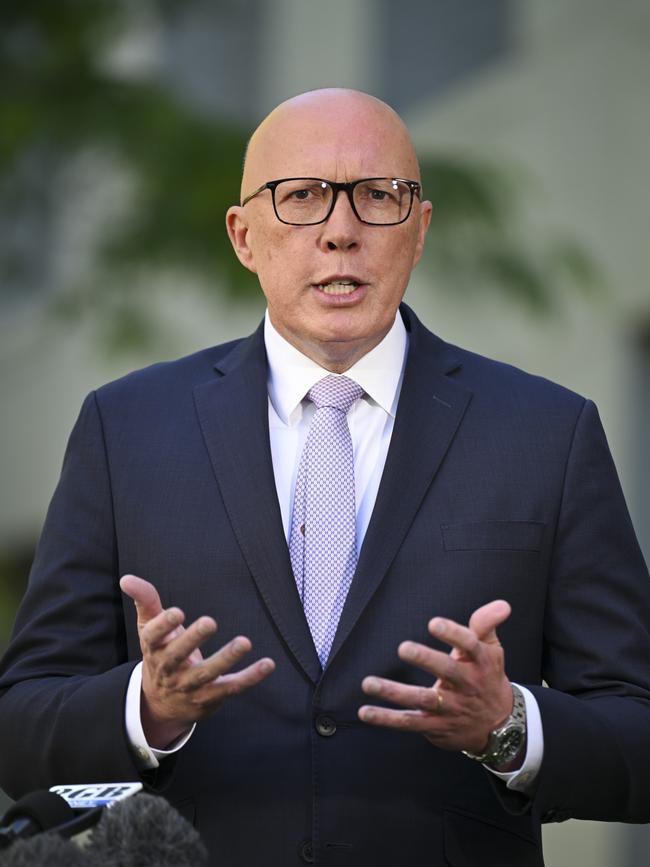

Asked to consider whether they were better or worse off compared with two years ago, 43 per cent told JWS their circumstances had deteriorated. That should raise alarm bells for Labor, as incumbents the world over in this year of elections have been pummelled for that reason. It will be Peter Dutton’s signature song next year.

But some voters are feeling the pinch more acutely and could prove the difference in a tight election. Among the 37 per cent who regard their standard of living as average, the proportion who think it has got worse since 2022 is 55 per cent; for those who regard their standard of living as poor, the proportion who think it’s now worse than at the previous election is 78 per cent.

“In marginal and semi-marginal seats that contain decent swathes of lower socio-economic neighbourhoods, this near 80 per cent opinion could have a serious bearing on election results next year,” JWS Research business development manager Tom Cameron says.

Another harbinger of doom for Labor is the latest National Australia Bank Australian Wellbeing Survey. While anxiety levels are down, sentiment about life worth, life satisfaction and happiness have yet to rebound from historical lows. The NAB report, published this month, found people showed enormous resilience during the height of the pandemic and looked forward to much better times. Then came the cost-of-living crunch.

“In this environment, stress is elevated and sentiment fragile as many feel flat after years of uncertainty and a lack of clarity over the path ahead,” the report says. “And averages continue to mask those pockets of the community who are feeling under significantly greater pressure.”

We can see how the parties are trying to win over younger voters by targeting housing and student debt in this era of “cozzie livs”. After months of Greens obstruction, Labor’s help-to-buy bill passed the Senate this week.

One of the government’s key pitches, supported by advertising, is “delivering 500,000 Fee-Free TAFE places” to cash-strapped young people. Labor’s changes to indexation rates on student debt, including for higher education, vocational training and apprenticeship support, also passed the parliament this week.

According to Education Minister Jason Clare, the move will wipe $3bn from three million loans. If re-elected, Clare says, from July Labor will cut a further 20 per cent off all student loan debts (costing as much as $16bn), raise the minimum repayment threshold for student loans and cut repayment rates. For someone with the average Higher Education Loan Program debt of $27,600 they will see about $5520 wiped from their outstanding loans next year.

There is political risk in this off-budget play, of course, as Labor’s student debt relief benefits professionals who will likely earn a fair premium over others during their working lives. It’s a wealth transfer – from non-tertiary educated taxpayers and graduates who settled their tab.

The Coalition’s policy of allowing first-home buyers to withdraw up to $50,000 from their superannuation (up to a maximum 40 per cent of their balance) may have surface appeal like other starter schemes. But it will push up home values and reduce retirement savings. Big Super’s custodians see it as pure politics and flawed policy as it doesn’t address the core issue of housing affordability: supply.

Labor’s coming policy set-piece is next month’s mid-year budget update. Jim Chalmers has prepared the ground for slippage in the bottom line, on and off-budget (where too much fiscal activism and subterfuge is occurring). There’ll be more to say in coming days, but already private forecasters such as Deloitte Access Economics have highlighted how the game is moving away from the political class.

A competitive election, with the government falling behind in the polls, is likely to lead only to more low-grade outcomes. Yet some perspective: look at our debt servicing and the underlying cash balance compared with other nations. Let’s not let Labor or the previous government off the hook, but we’re not following our rich peers down the S-bend.

As the federal parliament goes into recess over the summer, it’s going to be a torrid time for Albanese, likely the last of our five baby boomer prime ministers. Asset-rich Albo is not down in the ditch yet but, just like the Hordern when it went off back in the day, he’s looking up at the stars; it’s sweaty, ferocious and dangerous in the mosh.

Australia may be in a form slump, with several measures of living standards tracking sideways or going backwards. News on the cost-of-living squeeze and income growth is dire, with high inflation’s carnage exacerbated by the plunge in our productivity performance.