Amid global turmoil and consumer gloom, it’s mourning in Australia

The public mood is all about fear and risk and unless politicians can ease living costs, the electorate is tuning out.

Americans are flying high in a beautiful balloon, while here people feel like they’re squished at the back of the plane on a budget carrier. Can we get an upgrade?

Yet at his Madison Square Garden rally in New York this week, Donald Trump knew he was on safe ground by zeroing-in on grievance. “I’d like to begin by asking a very simple question,” the Republican presidential candidate teased the MAGA masses. “Are you better off now than you were four years ago?”

Despite the standout US economic performance, consumer sentiment is way down, near all-time lows. Forty years ago, the Gipper would have killed for these numbers. Instead, it’s moaning in America.

Something fundamental has changed since the pandemic, according to a new research paper, The Paradox Between the Macroeconomy and Household Sentiment, by three economists at the Brookings Institution, a progressive think tank in Washington.

“By most measures, consumer attitudes about the economy have been divorced from the underlying economic conditions, with consumers feeling as poorly about the economy as they did in the immediate aftermath of the Great Recession,” Ryan Cummings, Ben Harris and Neale Mahoney argue.

Sentiment is not wholly driven by rational and accurate perceptions, the authors say. There’s political bias; recessions (or the perception of one) make matters worse; and older Americans (more financially secure) are systematically more negative than younger households (which does not bode well, right, boomers?).

A US study last year found that when a Democrat is president, Republicans feel a lot worse about the economy, but Democrats feel only a little better. Quantifying it, Republicans exhibit a political bias in sentiment that is 2½ times stronger than that of Democrats. “Republicans cheer louder and boo harder,” the authors said.

There’s also a media bias to bad news and what The Wall Street Journal’s Greg Ip has described as “referred pain”. Events such as political and cultural conflict and intolerance, the pandemic, the border, mass shootings, crime, war in Ukraine and the Middle East may be negatively affecting views of the economy, even if national aggregates tell a brighter story, the Journal’s chief economics commentator wrote a year ago

It’s not simply a question of whether many working-class Americans report feeling as if they are subject to economic and financial pressure.

“Unfortunately, this has been an enduring feature of the American economy over the past 40 years,” the Brookings authors write. “At most points in time over the past four decades, if consumers lived under an identical macroeconomy as they have now, their feelings about the economy would have been largely positive.”

But it’s the residual impact of high inflation that has had the biggest bearing on US sentiment: price levels, “sticker shocks”, rather than the inflation rate, endure.

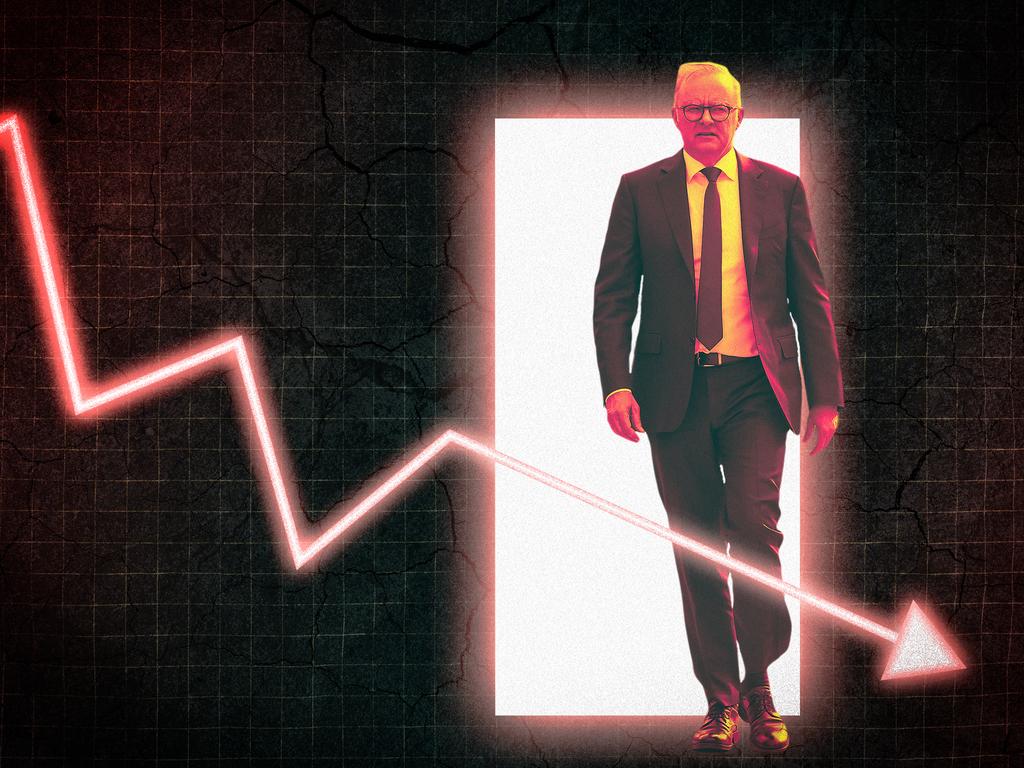

That’s the worry for Anthony Albanese as cost of living remains far and away the issue voters want the federal government to address. According to JWS Research, pessimism was at its (equal) lowest point in more than a decade in August, with twice as many people (40 per cent) saying the national economy was on the wrong track compared with those (18 per cent) responding it was on the right track.

JWS founder and senior researcher John Scales tells Inquirer that focus group research reveals voters are seeing everything through the lens of cost-of-living pressures.

“Voters are telling politicians that ‘if you’re not doing something about my cost of living then I’m not supporting you and I’m definitely not listening to you’,” says Scales.

The Prime Minister’s travails over Qantas perks have damaged his personal brand, but it’s inflation that’s hurting Labor’s standing with voters and buyer sentiment, as well as “smashing the economy”, to steal a line from the Jim Chalmers RBA hit parade. If there’s a special number to fix this salient issue for a prime minister losing altitude, here’s a clue: it’s between 2 and 3 per cent.

This week’s consumer price index for the September quarter showed annual headline inflation fell to 2.8 per cent (from 3.8 per cent in June) due to governments’ pain relief for energy bills and lower rent and fuel prices.

Inflation is inside the Reserve Bank’s target band, but there’ll be no interest rate cut for borrowers until at least early next year, given dismal productivity and a tight jobs market.

The RBA’s preferred inflation measure for policy moves, known as the trimmed mean (which removes the most volatile changes in the CPI basket), was 3.5 per cent, or around half its peak two years ago. Services inflation – think rents, insurance, childcare – is stuck at a percentage point above the underlying measure.

Since the start of the pandemic, consumer prices have increased by 19 per cent. Or 10 per cent since Labor came to power in May 2022. Wages, as measured by hourly rates of pay (excluding bonuses) have increased by 13 per cent (since March 2020) and 8 per cent (under Labor). The story is slightly better for minimum-wage workers, who have been awarded a 15 per cent (cumulative) pay rise by the Fair Work Commission in its past three decisions.

Pollster Scales says entrenched high prices mean consumers are learning to live with the consequences, adjusting their lifestyle, while attending first to basic needs such as mortgages and rent. “Inflation may be falling in a statistical sense but Albanese and Chalmers get absolutely no political pay-off or kudos for that with voters,” he says.

The Treasurer claims “we are on track and on target for a soft landing in our economy”. Maybe, but output is tracking sideways, spending growth is weak. Given record population growth, per capita national income has fallen for the past six quarters.

The public sector is behind most of the employment growth and is stopping a slide in measured GDP; expansionary budgets, especially in the frontier provinces and debt-addled Victoria, are also adding to the inflation problem.

The number of corporate failures has increased sharply in recent years, concentrated in small hospitality and retail businesses that rely on non-essential purchases. But there’s also angst in the construction industry, where insolvencies remain elevated, according to recent research by the RBA, “particularly among subcontractors, who have been affected by builder insolvencies, rising costs, weather delays and labour shortages”.

Still, the number of insolvencies, on a cumulative basis, remains below its pre-pandemic trend. Creative destruction, as it is known in economic circles, is part of capitalism; easy exits and entries drive business dynamism, innovation and productivity. Sounds heartless, but it’s true, and is the American way.

The rejigged stage three tax cuts from July 1 have been saved rather than spent. Commonwealth Bank senior economist Belinda Allen says while the income of the bank’s average household rose by more than 6 per cent across the year to September, driven by salary, rent, investment and government benefit payments, spending is up by less than 1 per cent.

On Thursday, after official retail sales figures showed a muted response by shoppers in the September quarter, her colleague Stephen Wu said “it will take interest rate relief to see a meaningful lift in household spending”. The nation’s major home lender and a swag of other market analysts this week pushed out to mid-February next year their forecasts for when the RBA would cut the cash rate. A single 0.25 percentage point easing would save a household with an average variable mortgage about $1600 a year.

According to Westpac’s Red Book, a deep dive into consumer sentiment, falling inflation and a growing belief interest rates have peaked are likely to lead to an improvement in buyer confidence. But it won’t be “smooth sailing”, says Westpac senior economist Matthew Hassan, because of considerable uncertainty about the economy. “Add significant risks of political turbulence around elections in the US and locally, and we may be in for a more unsettled period for sentiment,” he says.

With an election due by May, are Australians feeling better off than when Labor took power? That’s a dangerous subject to broach, even as the gloom lifts and unemployment is comfortably below its pre-Covid level.

Scales says the public mood is decidedly sceptical about pitches from politicians; party leaders talk, but working people, disengaged from the capital’s skirmishes and political news, aren’t convinced politicians have solutions to their daily problems or that their finances are going to turn around.

Non-partisans in the electorate, growing in number and hurting, are heading for the bunker, battening down the hatches when politicians come knocking. “The mood is more about fear and risk, with voters seeing things through the perspective of ‘loss from’ rather than ‘gain from’ when they think about politics,” says Scales.

It’s mourning in Australia.

Election day looms in the US, where the economy is aglow. Jobs, growth, incomes, business creation, investment, productivity, housing and the stockmarket – take your pick of the metrics – all are up, up and away.