In Germany 100 years ago inflation ran at 29,500 per cent – a month

Germany’s hyperinflation event in 1923 ruined an economy and ripped apart a society – paving the way for the rise of Adolf Hitler.

This year the Western world is rightly in a panic about inflation and the cost of living. Petrol in Australian capital cities is more than $2 a litre as energy costs burden industry and households. In April in this newspaper, Ewin Hannan reported that more than 30 per cent of Victorians seeking help from food banks this year had never before turned to a charity. Australia’s inflation rate is 6 per cent and falling.

In Britain, libraries are called “warm banks” and those who otherwise would be cold at home, unable to afford heating, are encouraged to spend their days there while being fed soup. Britain’s inflation rate is 6.8 per cent and falling.

Last winter almost 2000 New Yorkers stayed overnight in the subway system for the same reason, while others are seeking assistance from the hunger relief charity Feeding America.

Russia might have invaded Ukraine last year, killing thousands with Vladimir Putin hinting at a possible nuclear attack, but three months into the conflict, Europe’s worst since World War II, President Joe Biden still referred to inflation as America’s No.1 threat. The US inflation rate is 3.7 per cent and falling.

The West’s wrestle with its eroding prosperity bears no resemblance to the inflation catastrophe that engulfed Germany 100 years ago. The country’s inflation rate peaked at 29,500 per cent. A month.

Germany’s economy twisted in a hurricane of stupendous price rises that fed off themselves. And even though the German economy had been in distress for years, ever since the disaster of World War I, no one knew to expect this. The world had never seen a financial calamity like it.

The first ripples of what would in months become a tidal wave lapped at a most unexpected door – the shop of a popular piano maker in Saxony.

Wilhelm Schimmel was a cabinet-maker in the industrial city of Leipzig who had learnt how to make violins and then accordions. Fascinated by timber instruments – and living in the pianoforte capital of the world – he retrained as a piano-maker.

At first he worked in a rented shed and later bought his own small room to build pianos. Then he started hiring and training staff and before long, with business brisk and operating under the motto “the best possible instrument at a reasonable price”, he built his own 4000sq m factory in Leipzig.

He wasn’t the highest profile piano man in Germany – Steinway and C. Bechstein were famous across Europe and selling pianos to its royal families, including some to Queen Victoria that are in Windsor Castle to this day.

But Schimmel was up there and exporting instruments around the globe. Then in early 1923 something odd began to happen. Working and middle-class Germans began turning up wanting to buy pianos. In cash. These were less than wealthy families who normally wouldn’t own a piano. Mostly, they couldn’t even play them.

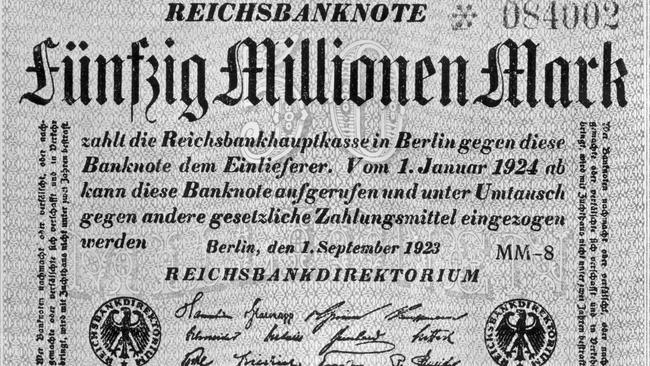

But soon, anyone in Germany who manufactured goods likely to retain their value was experiencing the same. The Weimar Republic’s great hyperinflation of 1923 was under way. Every cliche of galloping inflation played out over the next months as banknotes literally had less worth than the paper they were printed on.

The currency was then know as Papiermarks and things became so absurd so quickly that by the end of 1923 there was a 100 billion mark note.

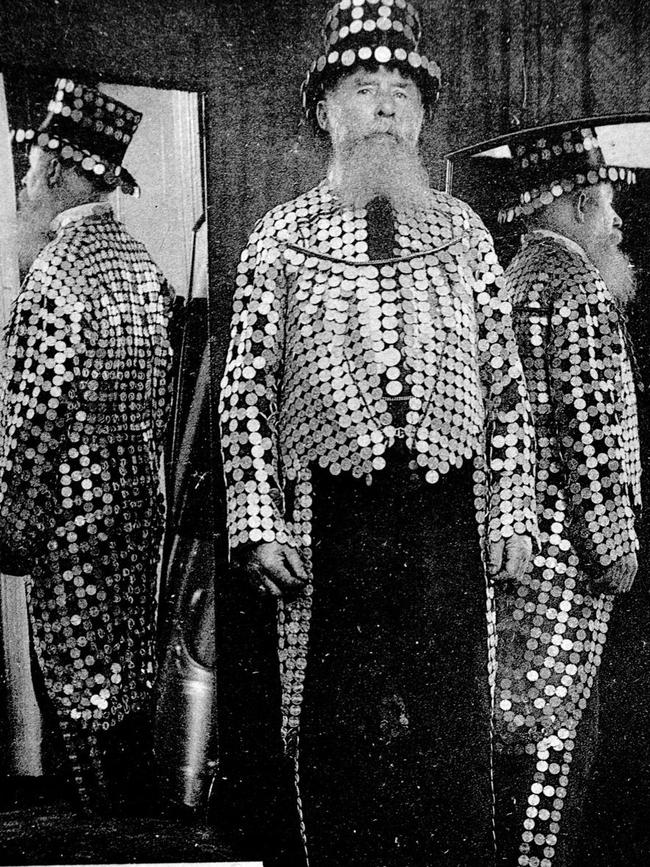

Children made kites out of worthless smaller denominations, and one man made a top hat and tails out of them along with the equally valueless coins and billed himself as Der Konig Der Inflation – the King of Inflation.

The irony of all this was that the chaos in the German economy was the direct result of another piece of paper that proved worthless: the Treaty of Versailles. Those European nations devastated by war – not just the unavoidable destruction and debilitating expense of it – wanted reparations from Germany and also to make the aggressor pay.

The Great War had not only brought the continent to its knees with unprecedented suffering but had obliterated a generation of its finest young men – eight million dead, seven million maimed – in whom these countries had seen their future. The mood that led to Versailles was understandable, but the vengeful, gothic politics of it all proved destructive.

At the time, the signing of the treaty was called the greatest moment in history. Germany sacrificed territory and colonies (parts of modern day Ghana and Papua New Guinea) and the reparations invoice was submitted for the equivalent today of $1550bn – that is not much less that the entire value of today’s South Korean economy. Germany’s leaders baulked at this clearly unpayable sum and it was revised down.

In The Gathering Storm – volume one of Winston Churchill’s six-book series The Second World War – the former prime minister says Versailles was “malignant and silly”. “The multitudes remained plunged in ignorance of the simple economic facts, and their leaders, seeking their votes, did not dare to undeceive them”.

The victorious allies planned to squeeze the vanquished “till the pips squeaked”, but this was bad for the global economy and made the already resentful Germans pessimistic about their future. History, Churchill added, would label these transactions “insane”. It was a “sad … complicated idiocy in the making of which much toil and virtue was consumed”.

Making things worse was the decision by Belgium and France in early 1923 to occupy the industrial Ruhr region of Germany when the fragile Weimar government defaulted on reparation payments of wood, iron and coal. This further weakened the German economy and the Weimar leadership, and an impoverished population, could see no way out.

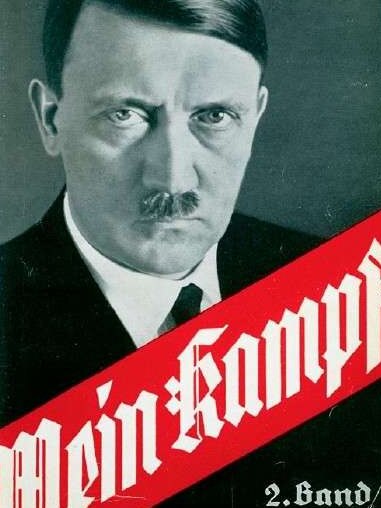

A year earlier, the newspaper editor and World War I veteran, Benito Mussolini, having rejected socialism, had, with 30,000 members of his National Fascist Party, marched on Rome and seized power. In Germany, an equally ambitious would-be politician, furious at this humiliation of country, tried to do the same. Few outside Germany, and neither that many inside, had heard of Adolf Hitler until his failed Beer Hall Putsch in Munich in early November 1923.

His plan to launch a popular revolution against the government from Munich quickly failed, and 16 of his Storm Troopers were killed. Hitler was arrested days later, convicted of high treason and sent to jail for five years. But he had made his point and a name for himself. He went to jail – almost house arrest really – for eight months, and wrote his hateful manifesto for a new Germany, Mein Kampf. We’d be hearing from him.

Hitler’s brand of nationalism was attractive to many repressed Germans who saw no future for the nation shackled to unpayable debts. The insane inflationary spiral of that same year rendered the country as unworkable as it would soon be ungovernable. Hitler may have failed in a Munich beer hall, but he still had his eyes on the prize. He wrote during his short stint in jail: “Instead of working to achieve power by an armed coup, we will have to hold our noses and enter the Reichstag against Catholic and Marxist members. If outvoting them takes longer than outshooting them, at least the result will be guaranteed by their own constitution. Sooner or later we shall have a majority …”

It is hard to digest the numbers involved in 1923’s hyperinflation, but some anecdotes help fill in the picture as the government kept printing ever more notes to chase goods from wages that were adjusted hourly. At the beginning of 1923 a loaf of bread was about 160 marks. By Christmas it was 200 million.

At restaurants, for those who could still afford them, waiters stood on tables at regular intervals to read out the menu’s revised prices. Employers and banks hired people to count the thousands of notes needed for the smallest transaction. Employees took suitcases to work to pick up their wages. On more than one occasion suitcases loaded with notes were stolen – but the thieves emptied them of their contents to make running away easier. Towards the peak of this madness a century ago, workers were paid twice a day, at different rates. During a lunch break, workers darted out with wheelbarrows of cash to spend the money on food and other necessities; they might not be affordable by 5pm.

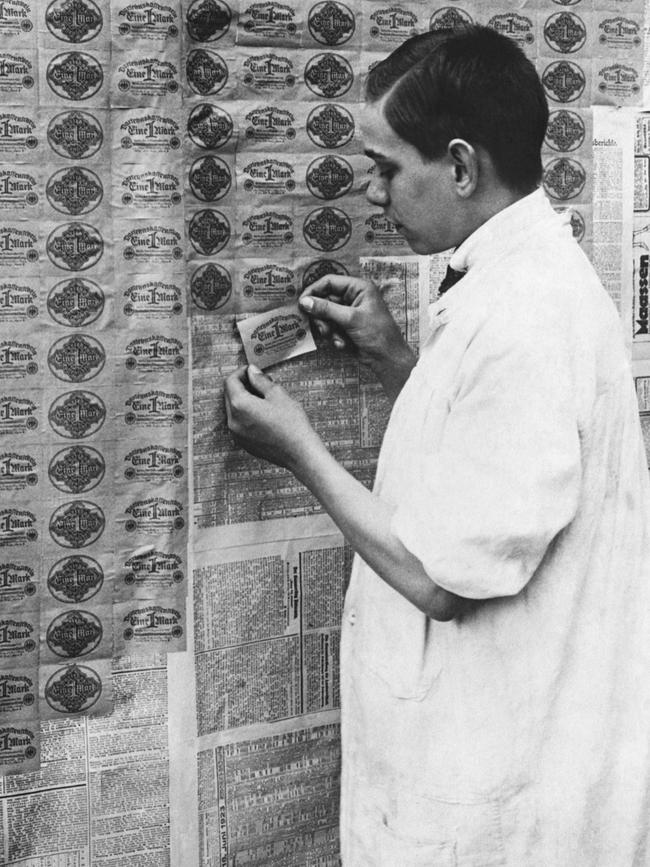

German families burned their Papiermarks to heat their houses. Children bundled notes with string and used them as building blocks. In many homes they became wallpaper. More than 125 printing companies did nothing other than produce banknotes for the government. Inevitably, a barter economy blossomed in parallel, but not everyone had tradeable skills.

In short order a five billion mark note was issued. Soon after there was a 50 billion note, and the madness peaked with a note “worth” 50 trillion marks. Many Germans benefited from it all by repaying mortgages with soon-to-be worthless notes. The social order was cracking, but the government was too timid to do the obvious to try to rein in the mark – set its value against gold or other commodities, and raise punishing taxes. It was even suggested by some economists that the German government may have sabotaged its economy to avoid reparations.

The nation was restive and a path for Hitler to the chancellorship may as well have been illuminated.

International economists and investment bankers, including JP Morgan, went to Berlin to try to come up with a stabilisation plan. None could be agreed.

But money has a way of sorting itself out. The US was owed money by the allies – loans they took to fund the war effort, which it refused to forgive – and the allies needed the reparations in turn to repay these debts.

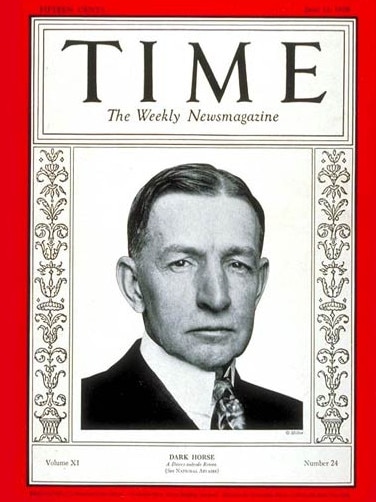

Late in the year the Allied Reparations Commission was formed, headed by Chicago banker Charles Dawes, that worked up a clever plan: reparations would be reduced, the US and Europeans would supervise the restructuring of the German economy, France and Belgium would retreat from the Ruhr, foreign banks would lend the Germans large sums and JP Morgan agreed to underwrite these, funding it all on the US stock exchange with the issue of bonds.

It worked to the point that Dawes was the 1925 Nobel Peace Prize winner. (In a long life of varied achievement he later became vice president to Calvin Coolidge, ambassador to London and, after teaching himself to play piano, wrote a popular tune he called Melody in A Major. The year Dawes died, songwriter Carl Sigman put words to it, and in 1958, recorded by Tommy Edwards as It’s All in The Game, it topped the US and British charts and has become a standard. Bob Dylan is the only other Nobel recipient to have written a No.1 song.)

Dawes’ plan worked to a degree, but German society was fractured and Hitler exploited the next banking crisis a decade on. He said he had a solution. The darkest days of the 20th century lay in wait.

Wilhelm Schimmel lived until 1961 and saw his pianos become the most awarded of any made in Germany, but in January 2016 his company was bought out by China’s Guangzhou Pearl River Piano Group for $39.2bn.

A German 500 million mark note, dated November 8, 1923, was for sale on eBay this week for $12.25.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout