Year that put Adolf Hitler on the road to total power

Few realised it at the time but the 1930 German election put the world on course for another devastating conflict

In the late 1920s most Germans had regarded him as slightly ridiculous — an intense, humourless, fanatical nationalist, running an irrelevant throwback of a political party. But at the 1930 election something changed. Suddenly Adolf Hitler went from being a rank outsider to a major political player.

His party had gone from just 12 seats in the Reichstag, the German parliament, at the 1928 elections, to more than 100 in 1930.

But while some may think Hitler’s rise to power was unstoppable, even at the beginning of the 1930s he and the Nazi Party still had a long way to go. Apart from being a relative minority ridiculed by larger parties, Hitler was not even a German citizen.

He was born in Austria and at that time his citizenship status remained in doubt. Austria refused to acknowledge his citizenship, but Hitler assumed he had become a German by serving in the German army in the war. He would only formally become a citizen in 1932, by which time he had found ways of overcoming some of the obstacles on his path to being ruler of Germany.

When World War I ended, many Germans were at a loss to understand why their country had capitulated so quickly.

Although they knew the war wasn’t going well, newspaper reports had failed to tell the whole story. When the Armistice was signed in November 1918, Germany’s borders had not been invaded, so the country’s ousted military leaders were able to spread the lie that they had been “stabbed in the back” by civilian leaders.

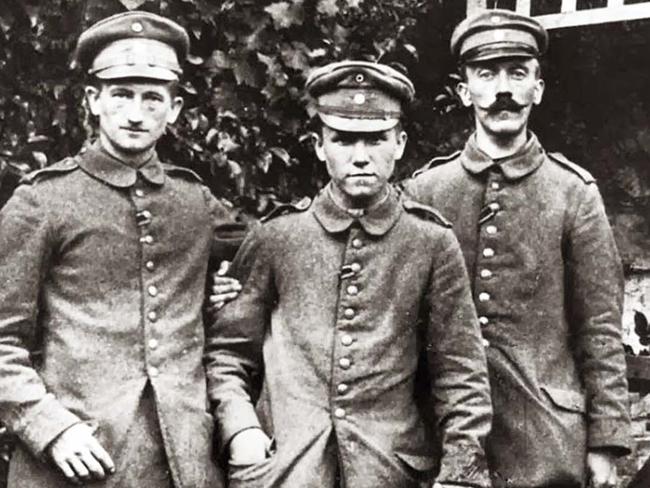

One of those who believed this wholeheartedly was corporal Hitler. Born in Austria in 1884, he had once aspired to be an artist, but had joined the Bavarian army at the outbreak of war in 1914. Decorated with an Iron Cross for bravery during the war, he was recovering from injuries received in a gas attack at the time the war ended.

After the war Hitler stayed with the army and worked in army intelligence, lecturing returned soldiers on the evils of communism. In 1919 he was sent to spy on the German Workers Party, a racist, nationalist party positioning itself as anti-capitalist but also as anti-communist.

Hitler liked their ideas and joined the party, impressing them with his oratory skills. In 1920 he took over as leader, renaming it the National Socialist German Workers Party, later dubbed the Nazis.

The party acquired a newspaper, the Volkischer Beobachter (National Observer), which became their propaganda organ, helping to develop a cult of personality around the party’s charismatic leader.

Even then Hitler believed the Weimar Republic, the democratic state that had come into being

at the end of the war, needed to be overthrown and a visionary dictator installed.

He saw himself marching at the head of an army to take power, like Mussolini had in Italy in 1922.

Joining forces with Erich Ludendorff, a World War I general, he attempted a revolution in 1923, storming a political meeting at a beer hall in Munich. Known as the Beer Hall Putsch, it failed badly and Hitler was arrested. His trial attracted national attention.

While serving his sentence for treason Hitler penned a rambling memoir titled Mein Kampf (My Struggle) laying out his ideas and his plans for Germany. He was released in 1924 and the book published in 1925.

Hitler renounced his Austrian citizenship and focused on his ambition for power. But party numbers had dropped after the failed insurrection. Hitler strove to bring membership back to the level it had been before the putsch, but with the era of hyperinflation in Germany over and a level of stability returning, he found it hard to gain political traction.

With the help of his propagandist, Joseph Goebbels, who had joined the party in 1925, Hitler built his image as a genius, the only man capable of returning Germany to greatness, by destroying the republic.

His opportunity came in 1929 with the death of Chancellor Gustav Stresemann, who had seen Germany through the problems of the 1920s. When the Wall Street Crash of October 1929 sent shockwaves through the German economy, Stresemann’s successors were not up to the challenge.

The Nazis launched a propaganda campaign positioning Hitler as the only man capable of doing something about the crisis. Thousands of Nazi speakers were sent out to engage with voters and propaganda films depicted the Nazi movement as bigger and more impressive than it was.

At the September 1930 elections the Nazis gained 18.3 per cent of the vote. But they lost ground when opponents exposed the cover up of the death of Hitler’s niece in 1931, raising the suggestion of an unnatural relationship between her and Hitler.

There were also stories about the leader of the Nazi party’s SA or Sturmarbeitlung (Storm Battalion), Ernst Roehm being a homosexual.

Nazi propagandists reacted by depicting Hitler’s human side, repairing some of the damage. Roehm was later disposed of in the political purge of 1934 known as the “Night of the Long Knives.”

With Hitler now a German citizen, in 1932 the party’s representation grew again to 37.3 per cent at an election noted for its violence and intimidation of voters.

The German president, Paul von Hindenberg, did not trust Hitler and refused to name him chancellor.

However, Hindenburg had a greater dislike of Chancellor Kurt von Schleicher and when von Schleicher was unable to resolve the political crisis that came about as a result of the 1932

election, Hindenburg appointed Hitler chancellor.

It was a move greeted with horror and disbelief within Germany, but even overseas people could see trouble brewing.

The Daily Telegraph asked: “Adolf Hitler — Chancellor of Germany. What next?”

In January 1933 a fire at the Reichstag was blamed on communists, allowing Hitler to call a national emergency and persuaded Hindenburg to use his presidential powers to suspend the constitution.

When Hindenburg died in 1934, Hitler combined the offices of chancellor and president. He now had total power.