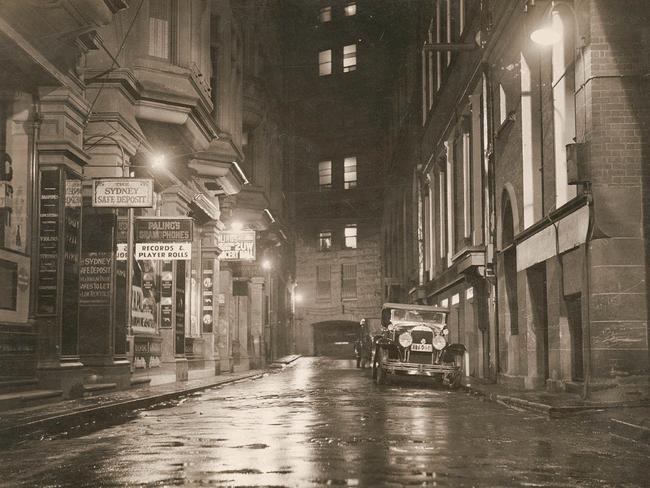

Razor wielding gangsters ruled the dark and dingy streets of Sydney

A crime wave in Sydney in the 1920s led to an outbreak of violence using cut throat razors

- Race to conquer skies to decades to win

- ‘Nasty’ Muriel’s Wedding almost did not make it up the aisle

Sydney was in the grip of a crime wave in the 1920s. While many residents were trying to go back to a normal life after the war, some of the thousands of soldiers who had returned home after serving overseas struggled to adjust, unable to get over the trauma

or to find their place in a world without military discipline or the extremes of war.

They also found the world of the Roaring ’20s in Sydney very different to the more sedate Edwardian-era town they had left.

Some of these men became involved in crime, falling back on the violent skills they had learnt in the army. Many even managed to hold on to weapons they had used in the war or souvenired from the enemy.

The affluence of the post-war city offered increased opportunities for criminals to exploit rules such as the ban on pubs staying open after 6pm, which had been implemented during

the war but stuck around after the war.

The criminal provision of booze after hours was known as the “sly grog” racket. Criminals also profited from drugs, prostitution and gambling, by providing them to a cashed-up public which was willing to pay. Gangs targeted people walking home after dark in the city’s narrow lanes and alleyways.

The police were hard pressed to keep up with the boom in crime, particularly the gun violence, so in 1927 the government introduced the Pistol Licensing Act, making it illegal to carry arms without a licence and to generally restrict the sale and possession of firearms. Police were able to nab anyone suspected of carrying an unlicensed gun, confiscate it and then slap them in prison.

There were stiffer penalties for people discharging firearms in public.

As a result members of organised crime gangs took to carrying straight razors, also known as “cutthroat” razors, instead of guns.

If a police officer found one on a man he could just say that he needed it to have a shave.

Razors had been used by gangs for years, and there are many reports of razor attacks happening before the gun law was passed. But razor gangs became particularly notorious in the late ’20s in poverty- stricken areas such as Surry Hills and Darlinghurst (dubbed “Razorhurst” by journalists) because of the cover offered by their narrow, dimly lit streets.

The razor gangs would threaten victims with mutilation, cutting the occasional face, leaving a scar by way of a warning to others. Sometimes an ear, nose, lip or finger would be lost, but often the fear of the blade was enough to frighten victims into doing whatever it was the criminal wanted.

Razors were far more personal than a gun; it took someone far more cold-hearted, bloodthirsty and used to hurting people to wield a razor with any skill.

By the late ’20s major gangs were being run by Kate Leigh and Tilly Devine, who both dabbled in a range of vices including sly grog, gambling and drugs. But Melbourne gangs had also begun moving into Sydney trying to get a cut of the action.

At times the gang rivalries turned into open warfare, when the razors would come out and leave many gang members scarred or dead.

Sometimes razor gangs dropped the razors and resorted again to guns.

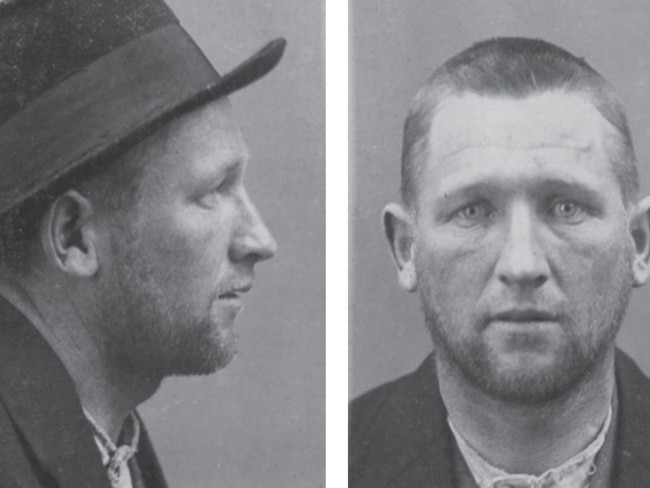

In June 1927 The Daily Telegraph reported the death of a gangster from Melbourne named Norman Bruhn, who was shot five times in the middle of a gang war. Bruhn had seen his attackers but refused to divulge their names.

One of the witnesses at the scene who had been questioned by police told a Telegraph reporter: “We don’t want the police in this. We can settle it ourselves.”

It was later found that Bruhn had been shot dead on the orders of John “Snowy” Cutmore, another blow-in from Melbourne, who was unhappy about Bruhn dealing cocaine.

Cutmore would soon return to Melbourne where he was shot dead

in October 1927.

The gangsters continued to try to settle it themselves, but the violence only worsened.

In 1929 the government passed an amendment to the Vagrancy Act, which added a clause allowing police to arrest and fine anyone who “habitually consorts with reputed thieves, or prostitutes, or persons who have no visible or lawful means of support”.

A special Consorting Squad was formed within the NSW police force and given virtually unlimited powers to lock away anyone they believed to be consorting with criminals.

It had a major impact on the gangs, breaking them up and ending the

reign of terror.