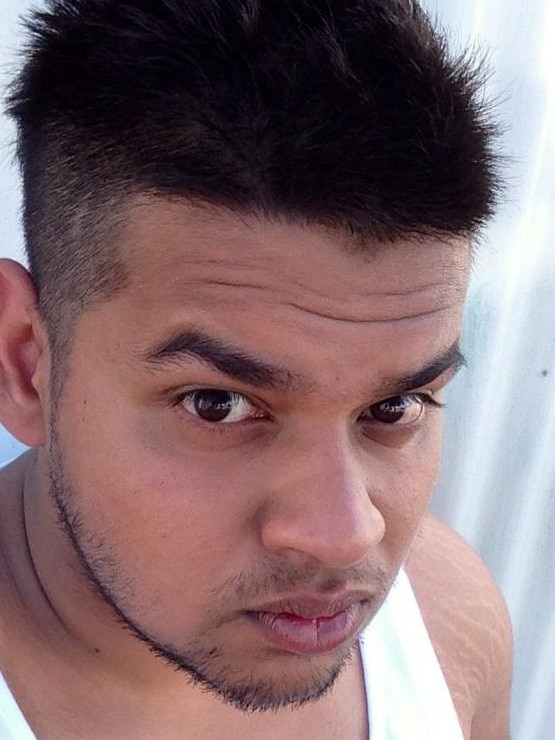

An Australian member of jihadist group Islamic State locked up in a Syrian prison has begged forgiveness from his parents and asked to come home, saying he posed no threat to Australia.

Mahir Absar Alam spoke after three years of being held incommunicado in a jail in the city of Hasakah, on the old frontline of the war with Islamic State.

He is one of about a dozen Australian men who have been detained without charge since the fall of Islamic State in March 2019.

A gaunt-looking Alam, now 29, believed the last contact he’d had with the outside world was with ASIO officers who had visited him in 2019.

He asked to know who had won the hit TV series Game of Thrones, which ran from 2011 to 2019, and inquired about the “Australian opinion’’ of people like him, who left Australia to join the Islamic State caliphate in 2014.

“I don’t have any problem with the Australian government or my country. I love Australia and I didn’t do anything wrong in Australia. I want to come back,’’ he told The Australian.

The former Melbourne accounting student denied being an Islamic State fighter, saying he had only ever worked as a nurse.

Asked whether he was or had been an Islamic State member, he replied: “I cannot answer this question for intelligence reasons and legal reasons.’’

The Syria Question

‘Give them a childhood’: mum

Pressure is mounting on the Albanese government to deal with the problem it inherited from the Coalition and repatriate Australian citizens from Syria.

‘I didn’t do anything wrong. I want to come back’

An Australian member of Islamic State locked up in a Syrian prison is begging for forgiveness from his parents and wants to come home, saying he poses no threat.

ISIS families stranded by domestic laws

Government is not legally required to bring ISIS families home, but should do so to meet international obligations, law expert says

Aid chief proves Syria trip can be done

For years, the previous government said it was too dangerous to extract women and children. Save the Children’s Australian chief Mat Tinkler set out to dismiss that claim.

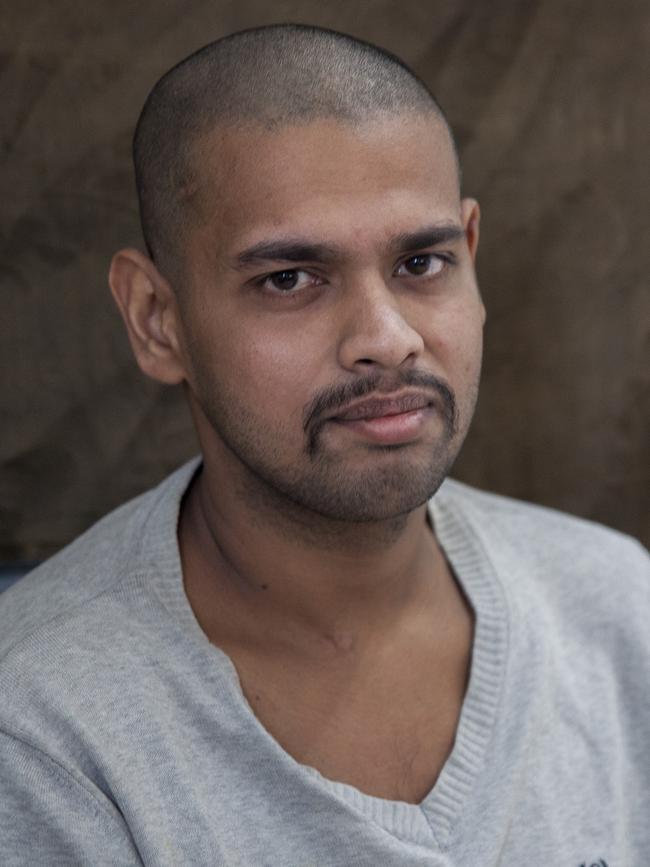

Roll call of the terror-linked prisoners

Australian men are among ISIS-linked prisoners in Syria.

Mystery over death of jailed Aussie teen

Officials and family seek answers over how Sydney teen Yusuf Zahab lost his life in the Syrian prison after an Islamic State attempted jailbreak.

Australian law does not require we bring Syria families home

Rather than safeguarding their rights, our legal system arms our government with extraordinary powers to prevent citizens from returning.

Aussie teen in Syrian prison feared killed

A 17-year-old Australian boy detained for three years without charge in a men’s prison in Syria is believed to have been killed after Islamic State attacked the jail trying to free their fighters.

Jihadi brides’ return ‘risky but ethical’

Repatriating Islamic State families undeniably brings security and legal challenges, but should be done for ethical and national security reasons, a leading counter-terrorism expert says.

Two of the saddest little girls you’ll meet

For the last seven years, Assya and Maysa Assaad have lived either under the rule of IS, or locked in a camp in the desert. All they want to do is go to school.

‘I go to sleep fearing they will be taken from me’

Mariam Raad wants stability and an education for her children, and a job for herself. But as a widow with four children living in a prison camp, her future is precarious.

Repatriated kids live quietly in community

The families of two dead IS fighters repatriated from Syria by the Australian government have been living in the community for several years.

Childhood lost: ‘Sometimes I feel like time has stopped’

Shayma Assaad had barely finished Year Nine in Sydney when she was taken to Syria, married off and impregnated. Hers is one of the most disturbing stories of all the Australian women trapped in al-Roj camp.

No exit and no hope in ‘torture’ camps

‘This is not a holiday camp, it’s not a refugee camp, it’s not a place where the basic needs of human beings are met in any way.’

Time to decide what becomes of those left behind

There’s little sympathy in Australia for fellow citizens trapped in Syrian camps. Instead, there’s a dangerous ignorance of the truth.

Jail swap sent Aussie mum, baby back to Islamic State

Sydney woman Nesrine Zahab has revealed how she fled ISIS while pregnant, only to be returned to the extremist group with her newborn baby in a prisoner swap.

Islamic fate: the lost heirs of Aussie terror

Pressure is mounting on the PM to repatriate Australian women and children held in camps for Islamic State families in Syria, amid fears their indefinite detention is leading to a national security disaster.

Asked whether he supported Islamic State ideology, he said: “It’s better I don’t answer this question either for legal reasons because we don’t know what will happen in the future.’’

Alam confirmed he left Australia with three other men, who made their way to Syria to join the caliphate via Thailand, Abu Dhabi, Cyprus and Turkey, before the other three men were killed.

“There were four of us from the same area who came together. We were friends, we came together. All of them died,’’ he said of his travel companions.

The involvement of two of the men – Mahmoud Abdullatif and Suhan Rahman – has been well documented, but Alam also named a fourth man, Omar al-Helou, as travelling with him from Melbourne in July 2014, shortly after now-dead Islamic State leader Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi had called for recruits from the al-Nuri mosque in the captured Iraqi city of Mosul.

The Australian has independently verified that al-Helou, who had not previously been publicly identified, was killed.

Abdullatif, 23, who died in early 2015, was married to Australian-Turkish woman Zehra Duman, who followed him to Syria and married him in late 2014.

Duman, who now lives in Turkey with her children after escaping the al-Hol detention camp at Hasakah, was Australia’s first identified “jihadi bride”.

Duman is free to live in the community despite Turkey sentencing her to seven years’ jail on terrorism-related offences.

She used social media to urge fellow jihadis to kill, stab and poison nonbelievers, and was stripped of her Australian citizenship.

Rahman, also 23, who called himself Abu-Jihad al-Australi, posted photographs of himself on social media posing with machine guns, and spending time with the notorious Sydney terrorist Mohamed Elomar.

Like Alam, he was a student born to Bangladeshi migrant parents. He is believed to have been killed in March 2015.

Alam’s name is spelled differently in various Kurdish autonomous administration papers, and he is registered at the prison as Maher Salem Alim and Maher Absar.

He is most usually referred to in Australia media reporting as Mahir Salem Alam.

Born in Sydney to Bangladeshi parents, Alam, who has a brother, was raised in the South Australian country town of Loxton before moving to Melbourne, where he studied accounting, including at Swinburne University.

He addressed his family directly: “I hope they can forgive me. I miss them so much. And I hope one day we will meet again.’’

Alam conducted his interview in fluent Arabic as ordered by his guards. The Australian is not permitted to reveal the location where the interview took place.

He confirmed he had travelled from Melbourne in July 2014, and was motivated to travel after watching a story about Syria broadcast on A Current Affair.

“They were showing a program on the situation in Syria and how people were suffering. I was watching the show and they were calling for people to come to help the Islamic country.

“I wanted to come to help because I didn’t have anything to do in Australia.’’

The then-22-year-old denied he and his friends had received help as they made the journey from Thailand to Abu Dhabi to Cyprus, then caught a boat to Turkey, entering Syria from the teeming Turkish city of Gaziantep, close to the border.

“We didn’t ask for help, we came by ourselves, we even came to Turkey without knowing how to get to Syria, and we asked people there.’’

He said he travelled to Raqqa, the IS caliphate’s Syrian capital, and worked at the National Hospital. Notorious Islamic State propagandist, paediatric doctor Tareq Kamleh, was at the same hospital, he confirmed, and other Australians came through for treatment.

“I was working as a nurse in the surgical ward,’’ he said, adding that Kamleh was “working with babies’’ and he didn’t see him much.

“I was working 24 hours, I was so busy, but a few Australians were there. Whenever they came to the hospital, I saw them but otherwise I didn’t.’’

He married a Syrian woman and had two sons, and while he believed they were alive, he’d had no contact with them for more than three years.

The Australian understands they are living in the community somewhere around Hasakah, the large Arab-majority city in Kurdish-controlled northeast Syria that remains under threat from Islamic State sleeper cells.

Alam said he was injured when the international coalition fighting Islamic State bombed the hospital, suffering shrapnel wounds to his back, arms and legs when the airstrike hit the hospital’s pharmacy.

The hospital had become a strategic asset for Islamic State and was among the last to fall when coalition-backed Syrian Democratic Forces finally drove the jihadis out.

Alam said he was injured a second time when Syrian regime forces attacked the car he was driving in 2018, suffering wounds again to his ribs. He transferred to the hospital at al-Mayadin, a city in the governate of the Islamic State stronghold of Deir ez-Zor, heading south until he eventually surrendered, alone, to SDF soldiers when Islamic State finally fell at Baghouz.

Alam said he didn’t know whether the Australian government had sought to strip his citizenship but he was not a dual national.

He asked if it was true that the Australian government had “boycotted’’ the Australian prisoners held in prisons around Hasakah for more than three years. The Australian was not permitted to answer that question.

More than 5000 men are currently detained in prisons around Hasakah. Details of the jails are tightly held because of the threat posed by Islamic State, which attacked the al-Sina’a prison at Guweiran in Hasakah in January with a truck bomb and hundreds of fighters.

In the ensuing riot and battle that lasted for 11 days, more than 500 people were killed and scores of prisoners escaped.

Prisoners are held incommunicado to stop snippets of information being fed to Islamic State that could assist such attacks.

Alam believes the last contact he had with anyone from outside was in 2019 when officials from Australia’s domestic spy agency, ASIO, came to see him.

“They just asked me if I am an Australian, without any details at all. Normal information, like what was your work like inside Islamic State,’’ he said. The visit may have occurred in August of that year.

He said neither Kurdish nor Australian officials had ever told him whether he would be charged, and he remained detained indefinitely without charge.

Asked if he wanted to go back to Australia and face the courts there, he replied: “Yes, for sure. I accept it (court and possible jail time), I don’t have a problem with that.’’

Asked if he posed a threat to Australia, Alam replied. “No.’’

“I don’t have any problem with Australian government or the Australian country. I wouldn’t do anything to hurt it. I’m not dangerous to Australia.’’

In 2019, he told the ABC he had never been an Islamic State fighter but had “unfortunately’’ answered the calls of al-Baghdadi.

He also said he had been charged by the Islamic State morality police after being caught watching Game of Thrones on his laptop computer in Raqqa.

More Coverage

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout