Humble atomic bomb scientist John von Neumann changed our world

The technology of digital computers and mobile phone is based on the work of Hungarian-born polymath John von Neumann. He changed our world.

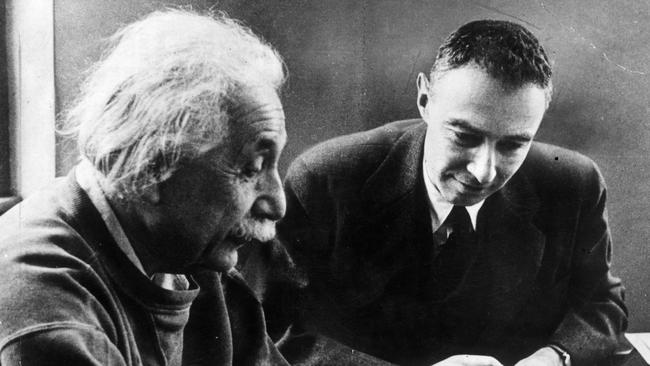

Isaac Newton had thought about it, but Albert Einstein came up with E=mc² – energy equals mass multiplied by the speed of light squared. It was good work. And then Einstein won the Nobel prize for something else altogether.

Einstein was extremely clever, and modern physics is based on his research and theories. He became the world’s best-known scientist and his surname a byword for brilliance. He had his shortcomings, such as sleeping with all those women who were not his wives.

He was confident too. Divorcing wife one, he promised in writing to give her the proceeds if he ever won the Nobel prize. He came good on that two years later.

He was regularly stopped on the streets of New York’s Long Island and asked about “that theory”. He would apologise and claim always to be mistaken for the famous professor. In 1999 Time magazine named him person of the century.

But the smarter fellow may have been down the corridor at Princeton University where they both worked. Indeed it was as if John von Neumann had arrived from the future.

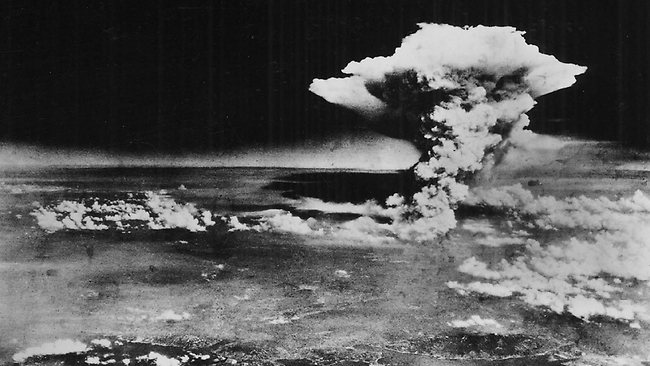

In a relatively short life, Von Neumann’s accomplishments in the fields of physics, mathematics, engineering and computer science are beyond astonishing: his theories and mathematical research built the base on which quantum physics – the understanding of sub-atomic particles and their interactions – is founded; he pioneered the thinking that led to digital computers; his maths was at the heart of the first atomic bombs; towards the end of his life he oversaw all atomic energy projects in the US; he was the Pentagon’s foremost defence scientist, and; today’s mobile phones owe much to his basic work on digital processing.

He also pioneered the concept of open source computing and insisted – sometimes by taking vendors to court – that all his innovations were free, unlicensed and for mankind.

Von Neumann was born to wealthy parents (his father knew the king) in Budapest at the end of 1903. It was then the capital of the 1000-year-old kingdom of Hungary that was soon to be violently convulsed by the events of World War I.

He was taught in several European languages, including English and French as well as Latin and Ancient Greek, and exhibited prodigious powers of mental computation; aged six, he could divide one eight-digit number by another. His two younger brothers were also very bright, but John stood out in a crowded family field.

When Von Neumann was born, German historian Wilhelm Oncken had not quite completed his landmark 46-volume history of antiquity, the Middle Ages and modernity. By 12, Von Neumann had read them all and three years on was studying advanced theoretical calculus. Before the age of 20 he was the author of landmark papers on maths.

His father thought he would be set up for better-paid jobs if he studied chemical engineering. So he did a course at Berlin University while completing a PhD in maths at Budapest’s Eötvös Loránd University, after which he turned around a paper on maths every few weeks.

He was born Jewish but converted to Catholicism in 1930. As the dark clouds of Nazism gathered over Europe he moved to America’s east coast and his family followed some years later. Once at New Jersey’s Princeton University he made a name for himself by always being immaculately dressed in stylish suits – even while on cycling holidays – and for loudly playing German marching music on a wind-up gramophone in his office, which annoyed his neighbours, including Einstein. He liked to work surrounded by noise and enjoyed crude humour.

He said that to solve problems he would think about them when he went to bed and often wake up with the solution.

But some simple things appeared to be beyond him. He could never really drive and it was reported that he bribed the New Jersey examiner to secure his licence. Once he was making good money he loved to buy Cadillacs at about $200,000 a pop in today’s money. They never lasted long. As Von Neumann explained following another accident: “I was proceeding down the road (and) the trees on the right were passing me in orderly fashion at 60 miles an hour. Suddenly one of them stepped in my path. Boom!”

But his enduring and unmatched genius was the key to him and to the regard in which he was held by some of the towering intellects of the 20th century, Einstein, Britain’s code-breaking genius Alan Turing and Manhattan Project director Robert Oppenheimer among them. Some of them believed Von Neumann the smartest human ever.

Last year’s star-studded blockbuster film Oppenheimer about the “father of the atomic bomb” – which has 13 nominations at Monday’s Academy Awards – unaccountably excluded Von Neumann, perhaps because his achievements may have overshadowed its star. Oppenheimer would have been appalled.

In 1955 a cancerous tumour appeared on Von Neumann’s clavicle bone, a malignant secondary cancer from an unknown source and possibly the result of being exposed to radiation at Los Almos. He could work dispassionately with numbers, physics, theories and even bombs, but he was frightened of death, and spoke to his mother about the possibility of a hereafter, explaining that he believed it likely there was a God. “Many things are easier to explain if there is than if there isn’t,” he told her.

He died less than two years after the initial diagnosis on February 8, 1957, a few weeks short of his 54th birthday. His simple headstone at Princeton records nothing of his monumental achievements, even though our world could not function without them.

Hans Bethe, a German theoretical physicist who also migrated to America and also worked at the Los Almos lab during the Manhattan Project, and who won the 1967 Nobel prize for physics, was once asked about his former colleague: “I have sometimes wondered whether a brain like Von Neumann’s does not indicate a species superior to that of man.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout