Computer viruses were seen as games before criminals moved in

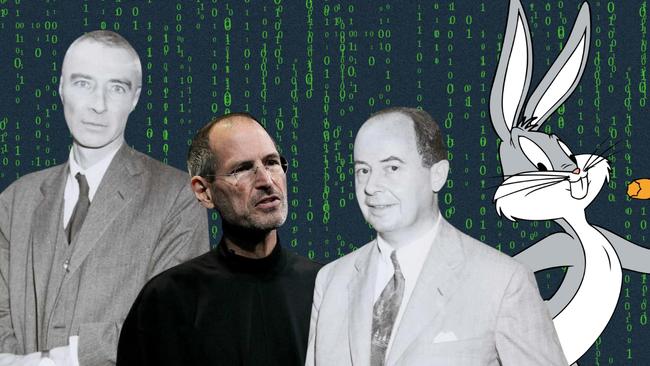

The notion of a computer virus – although that term would not be coined until 1983 – had been theorised by the Hungarian mathematics genius, and J. Robert Oppenheimer associate, John von Neumann.

It was Looney Tunes’ resident grump Elmer Fudd who named the first computer virus. He was famous for describing his perennial nemesis Bugs Bunny as “that wascally wabbit”. And when the first malicious computer virus was released 50 years ago in 1974, computer users, marvelling at the manner in which it so quickly multiplied, labelled their rascal the Wabbit.

The Wabbit virus infected only the IBM operating system into which it was introduced, so it did not spread through the modest networks then in place. But it acted just like the many viruses that would follow: it replicated itself, over and again, many thousands of times, consuming more and more of the operating system’s resources until the central processing unit slowed down and finally ran out of space and shut down.

The notion of a computer virus – although that term would not be coined until 1983 – had been theorised by the Hungarian mathematics genius John von Neumann in 1949 in his revolutionary paper Theory and Organisation of Complicated Automata.

A few years before he had worked on the Manhattan Project, and he was regularly photographed with President Dwight Eisenhower, Albert Einstein and J Robert Oppenheimer, the latter pair believing he was the smartest person on the planet.

He predicted global warming, and precisely so. Von Neumenn’s unparalleled genius also helped give birth to modern weather forecasting and the atomic bomb, it contributed to unravelling the secrets of DNA and the development of today’s computer revolution, including artificial intelligence and the mobile phone.

But he also understood that a computer – just like DNA – could be taught to replicate itself. The idea was so advanced and so complex that his 1949 “Complicated Automata” theory was confirmed only decades later, by which time he was long dead.

Almost every computer virus is designed to provoke what is known as a denial of service attack. They have long been considerably more sophisticated than 1974’s Wabbit, but the intention is the same and the manner in which they achieve it may be faster by a factor of thousands, but self-replication is its essence.

Wabbit wasn’t the first virus. It was the first “malware” – intended to do harm with malice. Until then the architects of computer had regularly developed their own viruses to test their systems’ resilience.

Wabbit came and went with little fanfare. Few people used computers then. Almost nobody did so at home. In 1974 Hewlett-Packard introduced a HP65 calculator, a bulky but magical piece of equipment – if you had the equivalent today of $8100 (but it came in a leather case).

In 1974, Bill Gates was 18 and about to start work at Honeywell; Steve Jobs was the same age but that year was taking LSD and seeking enlightenment in India – where he travelled to meet his spiritual master, Neem Karoli Baba, unaware the holy man had died months before.

From 1974, it was clear that a virus could disable a computer, and that somebody in the future would see this as a business opportunity: One group would use the same technology to protect software from infection; criminals would try to wipe out computer systems for the fun of it – like online graffiti vandals – while others, including state actors, Russian criminals and homegrown opportunists, would develop viruses to cripple computers and high-tech systems with a view to being paid a ransom, or gain political or security advantages.

The list of viruses that have crippled our now regularly interconnected computer systems – 68 million desktop computers were sold last year – is long, but companies are smarter at protecting themselves and users are more aware of the perils of opening an uninvited email or text message, although plenty of viruses come into our lives in even more clever ways today.

And some have cost us dearly: Hewlett-Packard estimated in 2020 that there were 350,000 pieces of malware found daily and that the annual toll to international business was $98 billion at 2023 prices.

The costliest by far has been Mydoom that attacked Microsoft Windows which is used by up to 1.4 billion users – one in six people on the planet. Mydoom was launched on Australia Day 2004. Its author remains unknown although it was thought to have been designed in Russia from where the first infected emails had been sent. It arrived with an attachment and were this opened, it then sent itself to every email address it located on that computer, after which it would guess at others with disconcerting accuracy. Such viruses are known as worms – a term first used in John Brunnel’s 1975 novel The Shockwave Rider, in which a computer hacker survives a dystopian world using his keyboard skills.

Mydoom contained the message: “andy; I’m just doing my job, nothing personal, sorry”. A line of its computer included “mydom” which became Mydoom as users realised the extent of the damage. Interestingly, it had been designed in such a way that it would not contact email addresses at Microsoft nor some leading American universities with advanced computer studies courses. An updated version released soon after cleverly disabled a computer’s antivirus software. It was discovered in 168 countries, but hardest hit were the United States and Australia. At one stage one in 12 emails was a Mydoom carrier.

New virus technology largely dealt with the issue but it resurfaced briefly in 2009 and sits dormant, but ready to work, on thousands of older computers to this day. The damage to business and the clean up over years may have cost $80bn – about the size today of the entire Bulgarian economy – according to Hewlett-Packard.

The WannaCry virus was in another league. Having found a potential flaw in its Windows program, Microsoft issued patches to remedy the vulnerability. Many users didn’t apply them while too many larger networks needing to work around the clock were reluctant to shut down their systems for the time required. On May 12, 2017, WannaCry was issued and within hours had infected 300,000 computers in 150 countries.

It locked the machines and demanded a payment in untraceable Bitcoin cryptocurrency. A few hours later, Marcus Hutchins, a one-time teenage hacker living in the west of England and working from the bedroom at his parents’ house, found a code to stop it, known as a kill switch.

By then hundreds of millions of dollars had been lost. Hutchins was hailed a hero, but was oddly shy of the publicity. Soon after, he was invited to a cyber security computer conference in Las Vegas with first-class airfares thrown in. But the FBI intercepted him with handcuffs as he was about to leave the US. He was changed with involvement in serious hacking incidents in the past (other hackers helped make his bail, stealing funds from hacked credit cards), later convicted and, after vowing never to enter the dark web again, was released. A headline at the time read: The Hacker Who Saved The Internet.

The US and British Governments later confirmed that North Korea had been behind WannaCry whose targeted victims had included hospital networks many of which reportedly paid up in Bitcoin despite government pleas not to.

About the same time another virus called CryptoLocker was released and spread around the world quickly. I fell for this one when an email arrived purporting to be from the Australian Federal Police. Not stopping for a moment to think why would that be, I opened it and the attachment and within seconds loud klaxon horns I was unaware had ever been installed on my laptop went off with menacing flashing images telling me my computer and all its files had been encrypted by CryptoLocker, but that I could pay a Bitcoin ransom and the code to unlock them would be sent to me.

In what seemed like a minute or two almost all my files – years of family photographs and 50,000 music files – were encrypted. Fortunately, and accidentally, although I did not know at the time, it was mostly backed up on another family member’s hard drive. In a panic I contacted the Australian Cybercrime Online Reporting Network (better known by the acronym Acorn), took the advice not to pay the ransom, filled in the forms – and never heard a word from them again.

Meanwhile, CryptoLocker seized computers across the globe and encrypted their files. More than $68m was paid in ransoms – about 40 per cent of victims were estimated to have paid, but not all were subsequently sent a code, and some were then asked for more. In any case incalculable damage was done to online assets, again including hospital networks, a particularly time-sensitive and vulnerable target.

This time, the FBI named its suspected culprit and offered a $4.5m reward for information leading to the arrest of a Russian man, Evgeniy Mikhailovich Bogachev, but he has never been found.

Significant viruses flourished in the same era, all cost millions and some billions: Klez, Sobig, ILOVEYOU, Zeus and CodeRed. But smarter software, smarter users and constant updates have largely rendered international ransomware a thing of the past. But this also comes at a significant cost. It is estimated that large companies spend about 12 per cent of their IT budget on security.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout