'The thing had to be done': Robert Oppenheimer

ROBERT Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, was a tragic genius.

COMETH the hour, cometh the person? If you have a malignant mesmeriser such as Hitler, there's some chance you will have a Churchill with a matching rhetoric and a finest hour.

That Stalin's murder of millions will have some kind of opposite in Roosevelt and the New Deal that dragged the US out of the Depression and set up the supremacy it enjoyed for the next half-century.

Yes, but if we are going to play this game of mix-and-match, do we think the Holocaust had its necessary complement in Hiroshima? Inside the Centre, a new and riveting life of Robert Oppenheimer, the father of the atomic bomb, makes you wonder but offers little consolation.

The day after "Little Boy" was dropped on Hiroshima in August 1945, Oppenheimer - as brilliant a figure as America has ever produced with as superlative a literary sensibility as a scientific one - said to his comrades at Los Alamos that his "only regret" was that "we hadn't developed the bomb in time to use it against the Germans".

Those words remain chilling and so does the fact that when Oppenheimer said years later in a lecture that he would do it again, a voice in the audience called, "Even after Hiroshima?", and he answered: "Yes."

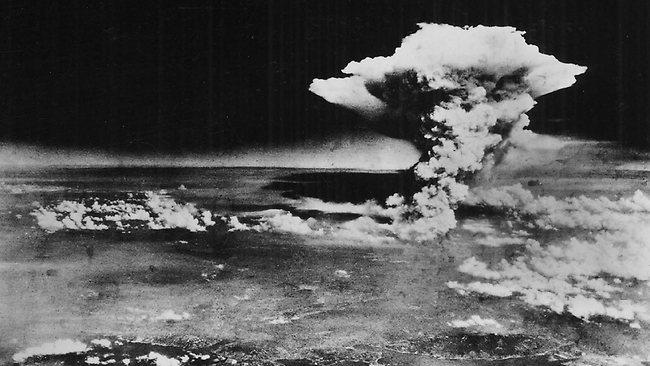

This is the man who can be seen on old television footage saying in his beautiful voice how when the mushroom cloud appeared above a test bomb and they knew the thing worked he thought of Vishnu, the many-armed god, in the aspect of Krishna the Lord: "Now I am become death, the destroyer of worlds."

Well, Oppenheimer was in some sense to be destroyed himself during the McCarthy era when the House Un-American Activities Committee denied him a security clearance and went a long way towards discrediting him as a dangerous lefty.

It was grossly unfair, though Ray Monk in this detailed biography says Oppenheimer sowed the seeds of his downfall - and that of many of his friends - because of the lies he told the authorities during the war, thinking he was shoring up his patriotic credentials.

The context was the climate of leftism that dominated American intellectual circles in the 1930s and later made some people think - as did the traitor Klaus Fuchs - that nuclear secrets should be shared with the Russians. Oppenheimer was approached apropos of this, tentatively at one point, by his friend Haakon Chevalier, an author and professor of French literature, but he refused the very hypothetical suggestion and nothing came of it. However, he told his fiercely loyal military associate General Leslie Groves and the FBI that Chevalier had approached a number of people, which was not true.

The betrayal of Chevalier was bizarre given the two men communicated with an extraordinary eloquence and meditated sensitivity. It was Chevalier who said to Oppenheimer regarding the bomb: "There is a weight in such a venture which few men in history have had to bear. I know that with your love of men it is no light thing to have had a part, and a great part, in a diabolical contrivance for destroying them." To which Oppenheimer replied, just as gravely: "The thing had to be done, Haakon. Circumstances are heavy with misgiving and far, far more difficult than they should be, had we the power to remake the world to be as we think it."

Chevalier had loved Oppenheimer and could not believe "what the mind had conceived and to what the heart consented". Oppenheimer said in a late letter to Chevalier, "It is not nearly as clear to me as it appears to be to you how much, in the past, at present, or in the future the shadow of my cock-and-bull story lies over you." Chevalier said despite his intentions, Oppenheimer's actions had been "incalculably disastrous both to me and yourself" and by "your unfathomable folly you and I are linked together in a cloudy legend which no truth will ever unmake or unravel". He went on to write a novel about Oppenheimer called The Man Who Would Be God.

Oppenheimer was the kind of man who was a living myth to his closest associates. A naturally princely character, a manifest genius in a Cocteau-like sense, he was said to make everyone fall in love with him. Moody, incandescent, hankering after wisdom and often close to madness, he seems to have been a bit like Hamlet.

Oppenheimer was born in 1904 to the purple of the German New York Jews who cultivated secularism like a scripture. He went to Britain, to Cambridge University, to study under Ernest Rutherford, fresh from his reconfiguration of the atom. The man Oppenheimer most admired was the great Dane Niels Bohr with his first-phase quantum mechanics. They were a dazzling lot, these physicists. Werner Heisenberg, the uncertainty man, who claimed he had no intention of developing nuclear weapons for Hitler and in practice certainly didn't succeed, spent his debriefing period in an English country house reading the whole of Trollope in English.

But Oppenheimer was extraordinary even by these standards. Late in the piece, when a magazine asked him for a list of the books that most influenced him, he named not only the Theaetetus of Plato and Dante's Divine Comedy but Bernhard Riemann's Gesammelte Mathematische Werke, the Bhagavad Gita and the Satakatraya: all of them read in the original languages. When asked how he had distracted himself on a train journey from Harvard in Massachusetts to Berkeley in California he said he read all three volumes of Das Kapital. He revered Proust and could quote in French the passage where the daughter of Monsieur Vinteuil arouses herself by defiling his picture.

He was an extraordinarily distinguished physicist at Berkeley even though there were jokes along the lines that "his ideas are always interesting, but his calculations are always wrong".

Monk argues that if Oppenheimer had lived a bit longer - he died in 1967 at the age of 63 - he would have won the Nobel Prize.

He was a genius of an administrator and the fact the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos - what ultimately came to be known as the Trinity Project (Oppenheimer said he was thinking of the Donne poem: "Batter my heart, three-personed God") - succeeded was due to the fact he could interpret to each other rooms full of solipsistic scientists and show the way forward, because of the way he could understand and reconcile different ideas.

Military men such as Groves adored him. J. Edgar Hoover and his henchmen loathed him and thought he was dangerous if not treacherous. The fatal committee hearing was so ruinous because it exposed a needless level of mendacity that looked profoundly suspicious (how could it not in the context of anti-communist paranoia?) but seems to have been a consequence of Oppenheimer's wild, artistic imagination.

Oppenheimer's theoretical defences of his one-time leftism could be impressive: "I became a real left-winger ... Much of what I believed then now seems complete nonsense, but it was an essential part of becoming a whole man. If it hadn't been for this late but indispensable education, I couldn't have done the job at Los Alamos at all."

At the same time he was acutely aware, and perhaps with more than a touch of melancholic instability, of the truck with the devil that his genius in lending the glory of science to the engines of destruction involved. "In some sort of crude sense," he said in a lecture, "which no vulgarity, no humour, no overstatement can quite extinguish, the physicists have known sin: and this is a knowledge which they cannot lose."

There is a sense in which Oppenheimer talks too well, like a figure in a poetic novel fringed with tragedy and religious illumination. He said reaction against the physicists was "the curse of Thebes", citing Oedipus Rex. After he went to Harry Truman to argue against a hydrogen bomb the president said, "I don't ever want to see that son-of-a-bitch in my office again."

In May 1954, Albert Einstein and Linus Pauling among others wrote in a magazine saying how dangerous and unjust it was to treat a man as a security risk simply because he said what the government of the day did not want to hear.

Oppenheimer passionately wanted nuclear weapons to put an end to war. His expression of this was characteristically subtle: "Today we live with massive retaliation and its better educated younger brother, deterrence, and with Cold Wars. They are less inhuman than war itself, and let us not forget it. But they are not very human, either."

It is very human, but not very worldly of the man who brought the world the atom bomb to think the US would be content to continue in a mutually imperilled stalemate with the Soviet Union.

In 1949 Oppenheimer became director of the Institute of Advanced Study at Princeton, where Einstein was a faculty member, and had among his guests TS Eliot - The Waste Land had been an influence. Like Eliot, he sought his consolation in the mists of spirituality though the cloud of annihilation was brighter than a thousand suns. Years earlier, Einstein had advised Oppenheimer against going along with a security hearing. The old German Jew who was the greatest scientist of the century saw clearly what the trouble was with the famous American-born fixer: patriotism.

"The trouble with Oppenheimer," he said, "is that he loves a woman who doesn't love him - the American government."

Inside the Centre: The Life of J. Robert Oppenheimer

By Ray Monk

Jonathan Cape, 830pp, $65 (HB)

Peter Craven was founding editor of Quarterly Essay.