Federal Budget 2022: Can economics trump compassion?

Scott Morrison is campaigning on a robust economic recovery, while Anthony Albanese offers an economy based on compassion and feminisation.

The real contest is jobs versus the zeitgeist. Frydenberg offers the most dramatic upsurge in labour market history – with unemployment falling to a 50-year low of 3.75 per cent – while Albanese offers an economy based on compassion, feminisation, more active government and a repudiation of Scott Morrison’s character. The defining tension is between the big economic picture and household feelings.

The key to the economics and politics of the 2022 poll is that Australia’s world-leading recovery translates into massive job creation but disappointing wages. The economy is robust but many people aren’t feeling the joy and aren’t happy about it.

In his budget reply on Thursday night, Albanese performed as the election frontrunner. Dismissing government demands that he provide an economic policy statement in reply to the budget, the Labor leader delivered instead a personal manifesto about his convictions, philosophy and judgment of the national mood.

Albanese wants an economy that “works for people, not the other way round”. He says that after their pandemic sacrifices, the Australian people “deserve” a better future. Albanese pledges to be a “caring” prime minister when “the cost of everything is going up” except your wages. So he promises that despite Australia’s record debt that must be tackled, “no family will be worse off” under a Labor government and “almost all families will be better off”.

Really? These are big claims. Initially they would rely upon the Frydenberg recovery. The point, however, is there are few limits to the Albanese compassion brand. Its ultimate expression came in his single announcement to rectify the aged-care crisis. Drawing upon the royal commission he referred to “unforgivable neglect”, residents “lying on the floor, crying out in pain” and loved ones suffering while “their carers, mostly women, are underpaid and overworked”.

The ALP leader will “put the care back into aged care”. For Albanese, aged care is not just a crisis he promises to confront. It symbolises the compassion gulf between the sides. He believes it highlights the election choice – Labor’s caring for people versus the government’s cynical budget trying to push the cost-of-living issue out beyond the election.

Albanese’s abiding faith is that “good government can change the lives of Australians for the better”. His five-point aged-care solution is based on government compassion. Every facility must have a qualified nurse on site 24/7. There will be more mandated care for every resident every day. The government will back the pay case for aged-care workers before the Fair Work Commission and fund the wage rise. To deliver better food for residents, some of whom are “starving”, he says, the government will impose mandatory nutrition standards.

And Labor will deliver higher funding – an extra $2.5bn on top of the government’s record $17.7bn last year in response to the royal commission. Putting people at the heart of the economy will underpin Labor’s cheaper childcare policy, its push for higher wages and more secure work.

Yet the fog of compassion seeks not just to appeal but to conceal. The sheer omission of economic policy as such in Albanese’s speech is revealing. Opposition Treasury spokesman Jim Chalmers has said a Labor government will seek fiscal repair by growing the economy, not austerity – the Frydenberg position.

There is scant evidence of any major difference between Liberal and Labor on the economic parameters. Don’t expect any major difference on the budget bottom line. There is no defining ideological conflict between the parties, and the policy differences will be far less than usual at elections.

Albanese is desperate not to frighten the Quiet Australians. He keeps saying he wants “renewal” – nothing radical, let alone revolutionary.

This is why an economic framing as the people’s friend is so important. It is pivotal to creating a point of distinction when the degree of policy overlap is actually conspicuous, at least so far. It is also why Labor’s effort to discredit Morrison is critical. The more voters dislike Morrison, the less they will scrutinise Albanese.

This is the principal fear of Morrison and Frydenberg. The Treasurer’s line is that Albanese is “trying to sneak into government” by pretending to govern like Bob Hawke and John Howard. Morrison said of Labor: “They’re not a small target, there’re a vacant space.” But Albanese, like most frontrunners, won’t be pressured into releasing his suite of policies before he is tactically ready.

Expect both leaders to run personalised, negative campaigns: Morrison is vulnerable because of mounting public dislike; Albanese is vulnerable because he remains an undefined commodity for many Australians. This points to a campaign heavy with character-based politics.

In this context, the extraordinary criticism of Morrison by Liberal senator Concetta Fierravanti-Wells delivered on budget night was damaging and calculated. Morrison has many failings and, from time to time, he has no doubt bullied and manipulated people. But Fierravanti-Wells went much further.

She said Morrison had “no conscience”, lacked a “moral compass” was “an autocrat and a bully” and used his faith as a “marketing advantage”. Having lost a winnable position on the Senate ticket, Fierravanti-Wells delivered a speech of spiteful revenge declaring that Morrison was “not fit to be Prime Minister”.

Morrison is often attacked by prominent women but this attack by a woman within his own ranks during the week when the government needed clear political air was extremely damaging and provoked a further pile-on, with Senator Jacqui Lambie conspicuous. Labor has been handed, yet again, fresh character ammunition to use against Morrison.

Assassination of Morrison’s character is now a blood sport. Once triggered by his own failings, it has assumed a life of its own. It is a cult that exists in its own right. The abuse becomes more reckless and seems designed to highlight the moral standing of the accusers. It is usually reported uncritically by most media. So, for the record, while Morrison may win or lose the election, there is no case, no evidence and no moral proposition that he is “not fit to be Prime Minister”.

The extraordinary nature of the government’s predicament is rarely highlighted. It goes to the contrast between the economics and the politics. Frydenberg’s budget forecasts lower unemployment lower at 3.75 per cent, growth higher at 4.25 per cent, the budget bottom line $100bn better, government spending high for a decade, inflation being contained and wages, finally, moving ahead of prices.

Such numbers should guarantee an election victory. As Frydenberg said, Australia’s recovery is “faster and stronger” than that of the US, Britain, Canada, Germany, France, Italy and Japan.

This follows a Covid-19 mortality rate that per head of population is the third-lowest among OECD industrialised nations. In future years, Australia’s pandemic performance will be seen as a significant historical feat.

The polls, by contrast, hovering around a 55-45 two-party preferred deficit, suggest a government of singular and abject failure. Has any government with such economic numbers ever rated so badly in the polls? The explanation, ultimately, resides not just in significant government blunders over vaccine supply and mismanagement of Omicron in January this year but to the “lived experience” of people.

The legacy of the pandemic is an electorate that feels bruised, frustrated, risk-averse and hostile to any economic shock therapy. The government’s problem is the pandemic exposed every flaw in the social infrastructure – in aged care, health and inadequate wages for health workers. Covid-19 has revealed the weakness of each nation – and the public has not forgotten. Chalmers says of the budget that nothing could compensate for the government’s “attacks on wages, job security and Medicare”.

The jobs/wages fracture is stark. Employment levels are running at 3.1 per cent above pre-pandemic levels, showing an economy, in Frydenberg’s words, with “real momentum.” More jobs mean less welfare, stronger demand, higher revenues and an improved budget bottom-line. Treasury makes the remarkable labour market statement in the budget papers that “there has been no long-run scarring impact from the pandemic.” Once, this would have been inconceivable.

But the opposition seized upon the wages story – real wages went backwards in 2021-22, and while they are forecast to nudge ahead from 2022-23 (growing at 3.25 per cent as opposed to the CPI at 3 per cent), this is progress off a fine margin. The trend for wages is stronger but the wage pattern across the economy is uneven.

In much of the workforce, people feel under pressures as prices rise and wages begin to pick up.

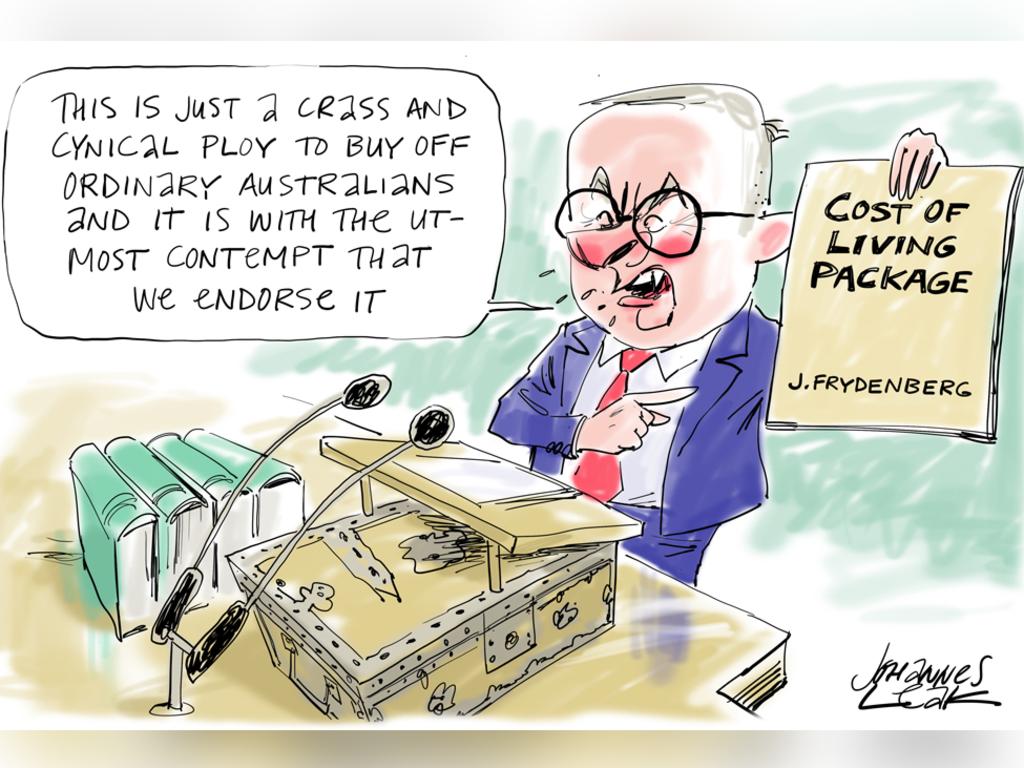

Criticism of the budget as an election bribe is exaggerated. The main three measures – the six-month halving of petrol excise, the one-off tax bonus for 10 million low and middle income earners, and the $250 cost-of-living payment – total $8.6bn. This is a tangible but far from reckless outlay. It is much less than John Howard and Julia Gillard offered in their final year.

The support is temporary. Economists are right saying there is no economic justification for such cash support given the strength of recovery, rising inflation and high deficits. But budgets are also political documents. Expecting the government eight weeks before an election to take no mitigating action in the teeth of cost-of-living pressures was never realistic. In truth, the cash support could have been much higher.

The numbers reveal a defensible trade-off between the economics and politics. They show across four years with extra revenue of $114bn the government sent $84bn to bottom-line deficit improvement and allocated $30bn to decisions around tax and spend – hardly a project in fiscal recklessness.

Whether such cost-of-living support works in political terms is a separate issue. Morrison and Frydenberg argued it met a justified public need. “Cost-of-living pressures are real,” Morrison told Sky News. “Australians need that support now, just like when we introduced JobKeeper. It was needed then. It was temporary.”

Frydenberg was unequivocal. The new law terminates the fuel cut on September 28. The politics will be ugly for whoever wins the election – facing the prospect of rising petrol prices and subsequently seeing the phase-out of the low- and middle-income tax offset that the Treasurer said “was only meant to be temporary”.

There is a real spending issue for Morrison and Frydenberg – but it is not this pre-election budget, rather what happens after the election. The budget shows a changing Australia in terms of needs and values. Spending as a proportion of GDP in four years time will still be running at 26.3 per cent of GDP, and a decade down the track it will be 26.5 per cent of the GDP.

This is a new spending plateau above the level of the Rudd-Gillard period and driven by deep structural changes – demography, the NDIS, aged-care demands, social services, defence and national security. By historical tests, the Morrison/Frydenberg government has become a big-spending government – and this higher level of spending can be expected to remain under Labor.

This brings into focus the optimism in Treasury’s budget forecasts – that the deficit will more than halve over the next four years and halve again so that by 2032-33 the deficit will be down to 0.7 per cent of GDP. Yet private sector economists warn budget savings of $40bn annually will be needed to reconcile the books. Neither side of politics displays any appetite at this point to tackle such hard decisions. This is the unannounced story of the election.

The economic and emotional battle lines are drawn for election 2022. The Morrison government is running on a robust economic recovery with stunning numbers across Josh Frydenberg’s budget, while Anthony Albanese will campaign on the “lived experience” of people who are unhappy about living standards, costs and services.