Ethiopian nun created her own musical language at the piano

From Ethiopian nobility, Emahoy Guèbrou had a privileged childhood, but traded it in for a life of poverty and service.

OBITUARY

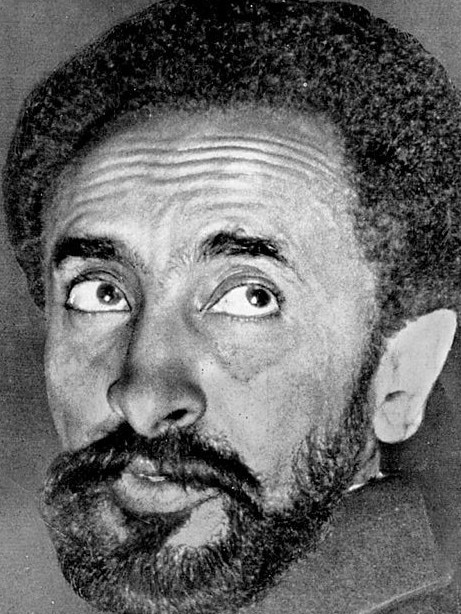

Emahoy Tsegue-Maryam Guebrou

Nun, musician. Born Addis Ababa, December 12, 1923; died Jerusalem, March 27, aged 99.

Faith has written and preserved music for centuries. And two profoundly exceptional musical chapters of the 20th century were driven by it.

Unclassifiable, aberrant and unrelated to anything before it, Armenian mystic George Gurdjieff “wrote” about seven hours of music for piano in the mid-1920s. He couldn’t play an instrument; he hummed, sang and tapped out tunes to his Ukrainian friend, Thomas de Hartmann. Not long before his own death, de Hartmann set these down across half a dozen shellac 78s in 1956, music that has inspired the likes of Keith Jarrett, Robert Fripp and Kate Bush, and which is credited with creating the New Age movement.

Gurdjieff said his tunes had come to him after he stayed in remote monasteries and tried to recall the music he heard there.

Emahoy Tsegue-Maryam Guebrou, an Ethiopian nun, was a gifted piano player and violinist who lived a large part of her life isolated and barefoot, bound by monastic vows of poverty.

Her unusual, precise music, spartan but insistent, confidently eschewed traditional adherence to rhythm or scales, perhaps influenced by Ethiopia’s unique five-note system, and floated about anchored only to her belief in it as she created an idiosyncratic musical language. And, like Gurdjieff’s, her music might have been lost but for one fan’s commitment to make it more widely appreciated.

Guebrou’s family had been wealthy. Her father, Kentiba, 78 when she was born, was an influential Ethiopian intellectual, and friend of emperor Haile Selassie. In 1929, aged six, she and a sister, Senedu, were sent to a Swiss boarding school. Guebrou studied piano and violin, and proved herself gifted at each. She practised up to nine hours daily. The girls returned to Addis Ababa just before Italian dictator Benito Mussolini invaded Ethiopia, which he planned to incorporate into his country’s growing African empire, subduing the locals with mustard gas left over from World War I.

Those members of the Guebrou family not murdered were sent as prisoners of war to Asinara, an almost uninhabited island off the northern tip of Sardinia. Later they were moved to the mainland near Naples. They returned to Addis Ababa when the British liberated Ethiopia in the first years of World War II.

After the war Guebrou studied violin in Cairo under Polish master Alexander Kontorowicz, the concert violinist to King Fouad of Egypt, and later for the returning Selassie. Guebrou also would play and sing for the emperor and became the first woman to enter her country’s public service, working in foreign affairs – she spoke at least six languages.

She was offered a place at London’s Royal Academy of Music but, for reasons she could never quite recall, Ethiopian officials withheld the necessary paperwork. Frustrated, she decided it was a message from God and turned instead to a religious life, becoming an Ethiopian Orthodox nun and living in a remote mountaintop monastery in the country’s north.

For 10 years she lived frugally, hearing and playing no music. Returning to Addis Ababa, she slowly came back to music listening to Beethoven, Bach and Strauss, and aware of the capital’s embrace of new jazz styles and rhythm and blues. She began to play her own unconstrained music in which fleeting moments might remind you of Duke Ellington’s adventurousness or the unorthodox stylings of Thelonious Monk. She had always listened to church music – Ethiopia’s is some of the oldest.

Helped by Selassie, she had made an unnoticed album in 1967 to raise money for homeless children. Very rarely she might play in public. In 1984 she moved to the Ethiopian Church in Jerusalem, living the rest of her life in a small room with some old reel-to-reel tapes and a cassette deck on which she would sometimes record her playing. Above her bed was a framed photo of Selassie. Under it were old Ethiopian Air Lines bags containing 150 manuscripts – music she had written through the years, some of it brief flourishes of notes on single sheets, others extended, multi-movement pieces.

Helped by a friend, a dozen of these were published and others started to play Guebrou’s music. It came to the attention of French musicologist Francis Falceto, who had been documenting Ethiopian music. In 2006 he issued 16 tracks by Guebrou in his widely heard Ethiopiques CD series.

The music world was taking notice. She was 82. Her songs were used on the Oscar-nominated documentary Time, and then behind the Netflix movie Passing and in an Amazon ad campaign.

Next month a second album of her music, called Jerusalem, will be released.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout