Out-of-control immigration destroys British politics and society

Across the West, liberal judges are thwarting popular demands for government to take control of national borders.

The immigration issue has eaten British politics. Not just any immigration but uncontrolled immigration, legal and illegal. It’s roiling British society and throwing the economy wildly out of whack.

The immigration issue is determining election results all over the Western world. Joe Biden’s woeful record on failing to stem illegal immigration to the US, along with inflation, was the greatest cause of Donald Trump’s remarkable comeback election victory.

It’s the dominant issue in the German election on February 23. The Alternative for Germany party, which other parties describe as far right, could come second, perhaps winning all the states of the former East Germany. It takes the strongest position favouring control of Germany’s borders. The Christian Democrats have moved in the same direction.

A car driven by an Afghan asylum-seeker rammed an innocent crowd in Munich on Thursday, badly injuring dozens of people. Late last month another Afghan asylum-seeker attacked innocent people in a park in the Bavarian city of Aschaffenburg, killing two, injuring more. These attacks are galvanising German opinion.

In Britain, Nigel Farage’s Reform UK party has promised “net zero” immigration. Both Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch and Labour Prime Minister Keir Starmer have moved to much tougher immigration stances. All week British television was showing footage of British officials arresting and deporting illegal immigrants.

Across the West, one of the biggest fights is between governments on one side, with an overwhelming desire by the electorate to take control of borders, and liberal judges on the other side, who have effectively come to the view that almost any deportation is a human rights breach.

Thus Italy’s Prime Minister, Giorgia Meloni, the strongest national leader in Western Europe today, is continually prevented by Italian courts, interpreting European law, from deporting illegal arrivals, and those picked up at sea as they approach Italy, to assessment centres in Albania. British courts stopped the previous Conservative government from sending illegal boat arrivals to Rwanda for assessment. These schemes and others emulate the Australian policies pioneered by John Howard and Tony Abbott.

Former Conservative security minister Tom Tugendhat, who was a leadership contender after the election and is now a backbench MP, tells me in his Westminster office: “Australia is the only major Western nation to establish the legitimacy of its immigration program.” Abbott’s action in stopping illegal immigration by boat after it had once before been stopped under Howard, then come roaring back under Labor, was an epic achievement of historic significance, for which he enjoys the highest reputation among Western policymakers.

All the societies mentioned – the US, Britain, Australia, Germany, Italy – have welcomed immigrants in the past. Almost all Western societies are now multiracial and ethnically and religiously diverse. Britain has an Opposition Leader, Badenoch, of African origin, immediately after having a prime minister, Rishi Sunak, of Indian origin. The US had an African-American president, Barack Obama, and later an African-American vice-president, Kamala Harris. And so on.

The almost insane academic and political left presents Western societies as inherently, distinctively and wickedly racist, so much so that half of young Brits believe their society to be racist.

In fact Western nations are the most anti-racist nations on earth and in human history. No nation outside the Western tradition regularly sees members of ethnic minorities become national government leaders.

The crisis across Western politics today is that immigration has run totally out of control in three ways – its sheer size, its low-skill and sometimes culturally incompatible composition, and the grave inability of governments to protect their borders or control their immigration numbers.

In this, as in many areas of policy, the courts have become effectively the enemies of democracy.

Many traditionally pro-immigration figures, such as this author, now recognise that while a well-balanced, controlled and properly proportioned immigration program makes a big contribution, today the situation has run dangerously out of control in many Western societies.

Three cases highlighted in Britain this week underline the disconnect between courts and public sentiment, and the tremendous constraints courts impose on elected governments.

The British government was prevented from deporting a convicted Albanian criminal back to Albania. It was deemed that such a deportation would prevent his enjoying a normal family life, which is guaranteed under the European Convention on Human Rights, of which Britain is still, balefully, a member.

The Albanian criminal’s 10-year-old son, the immigration tribunal was told, was sensitive to certain types of food. According to British press reports the only example given was that he didn’t like “foreign chicken nuggets”. So the immigration tribunal ruled it would be “unduly harsh” to remove the father from Britain as the son might go with him and suffer the indignity of foreign chicken nuggets. Therefore the Albanian criminal could stay in England. The case is ongoing.

In another case, a Nigerian woman who came to Britain in 2011 had failed in eight attempts to secure asylum status. Each time she appealed and was granted further time. Several years after her arrival in Britain she joined a group regarded as a terrorist outfit in Nigeria, the Indigenous People of Biafra.

According to British media reports, the court ruled eventually that she had joined that group solely to establish, under the international refugee convention, that she suffered “a well-grounded fear of persecution” should she return. Although the court determined her motive was to gain asylum status, it nonetheless also ruled that, because she had joined that group, she would indeed suffer persecution if returned home and so she was granted asylum in Britain.

In a third case a family of Gazans was able to convince a court to grant them residency under a program the government set up explicitly to allow Ukrainians to come to Britain.

Three cases may not in the scheme of things be all that important. But there are tens of thousands of appeals awaiting determination. There’s a huge backlog.

Moreover, if nobody, or very few people, are ever really deported, that builds pressure on assessment authorities never to rule no to asylum claims.

The Starmer government makes a lot of the fact that it has increased forced deportations since coming to power. But it has in total deported fewer people than the number who have arrived in Britain illegally by boat over the same period, which inflow has increased since Labour came to office.

But that is not the major problem. Tens of thousands of people become illegal in Britain by arriving legally on one visa or another, then simply over staying. If any action is ever taken against them, they claim asylum and the appeals process goes on forever.

Even that is not the biggest problem. The biggest problem is legal immigration, yes legal immigration, which has run totally out of control.

Britain, like most Western nations, runs an extremely generous welfare system. Even before qualifying for the full welfare rights of a British citizen, anyone who manages to get to Britain becomes eligible for a range of government services, from emergency accommodation to healthcare.

This is a magnanimous and compassionate approach from the Brits. But it’s completely unsustainable. There are literally billions of people on the planet who would like to live in the US, Britain, Australia or any other advanced Western society with generous welfare benefits. It’s utterly impossible to accommodate them all. This basic, unavoidable, laws-of-physics contradiction, which progressive left politicians denied altogether until a minute ago, now drives much Western politics.

Perhaps the greatest era of successful immigration was from the last decades of the 19th century to the first decades of the 20th century, especially to the US. In those days the US, like all other societies, had no welfare state to speak of. But it had a strong national and civic identity. Immigrants were attracted not by welfare payments but by opportunity.

Immigrant courage and industry were celebrated in American literature and art. The greatest examples are the frontier novels of the Pulitzer prize-winning Willa Cather from a century ago, especially books such as My Antonia and O Pioneers! Immigrants were also powerfully attracted by the political freedoms of societies such as the US, Britain and Australia.

Much legal immigration is still good for the people who come and the societies they come to, but the scale of programs is threatening to overwhelm societies. It’s certainly overwhelming Britain. Governments, in thrall to particular industries and various lobby groups, set up essentially demand-driven programs that they then find it almost impossible to bring under control.

Thus the Albanese government was absurdly seen as unreasonable for holding the idea that the federal government could impose a cap, any cap at all, on the numbers of overseas students coming to enrol at Australian universities, even though health and housing services were under deep strain, a substantial number of students were coming to secure immigration rather than education, and the university experience for Australian students was compromised when the system was overwhelmed.

The scale of immigration in Britain is simply staggering. In 2024, some 1.2 million people came to live in Britain. That’s not a net migration figure, because some hundreds of thousands leave per year as well. But even the net figure tends to be not too far south of a million. That has been the case since 2021 and looks likely to continue. With a total population of 69 million, the UK is absorbing, badly, huge numbers every year.

Leaving aside whether there’s a significant minority who don’t accept British values, liberal democracy, elements of the universal rule of law and the like, British services simply can’t keep up with the demands of this influx.

The British voted to leave the EU in part to regain control of their immigration program.

The Conservatives, especially under Boris Johnson, failed utterly to regain that control and deliver the lower immigration they promised. More than anything, that’s why the Conservatives lost office so resoundingly.

Despite the high-publicity expulsions, Starmer’s government is taking actions that will make the problem worse. It’s reinstating the right of people who arrive illegally to eventually claim citizenship. It has also made it clear that there are no circumstances under which it will leave the European Convention on Human Rights. Because that document is so vaguely worded, highly liberal British courts interpret abstract nouns in such a way as to stymie government efforts at enforcement, no matter what the electorate wants.

The true costs of this situation are starting to become apparent. Badenoch argues that the immigration of the past few years alone could end up costing the British state more than £200bn ($398bn). This figure is based on think tank work that is pretty straightforward. The Centre for Policy Studies and the Office of Budget Responsibility examined the fiscal implications of 800,000 predominantly low-skill immigrants from the past three years eventually becoming permanent Brits.

Low-skill immigrants become low-paid workers, if they get a job. Welfare and transfer payments are now so voluminous that a low-paid worker who arrives in their 20s and lives to 80 will receive more than £500,000 more from the government than they will pay in taxes. Because Britain’s mass immigration has skewed towards low-skilled immigrants, this will cost the state hundreds and hundreds of billions of pounds over the decades.

If the current high rate of immigration continues, and the current low British birthrate that is partly a consequence of the cost of housing and the shortage of services continues, then a decade from now one quarter of Britain’s population will be born overseas.

Britain then becomes less a nation and more just a place where a lot of disconnected people live.

Says Tugendhat: “We (Conservatives) promised low immigration and delivered the reverse. It was a huge failure. You simply can’t run the levels of migration we’re running and maintain the welfare state and our level of prosperity.”

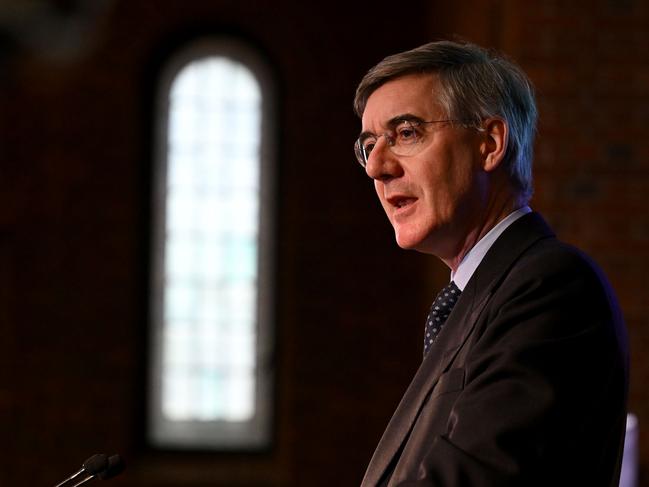

I discuss these issues with another thoughtful conservative, Jacob Rees-Mogg. Also a cabinet minister under Johnson, Rees-Mogg lost his seat at the 2024 election. He comes from a different wing of his party from Tugendhat. They are two of the most thoughtful and competent politicians I’ve met anywhere. Rees-Mogg is also surely the most unfailingly courteous. I speak to him in his well-lived-in but quite charming London home, sitting in front of a large bookcase that houses the complete works of PG Wodehouse and seemingly endless editions of Wisden Almanacks.

Rees-Mogg stresses that he has no criticism, indeed much admiration, of most of the people who’ve come to Britain but, like Tugendhat, says the number is simply way too high. This reflects, as he tells it, a series of British government mistakes going back decades.

As far back as Tony Blair’s prime ministership, the British bureaucracy vastly underestimated the number of permanent migrants who would come to Britain, especially from newly admitted EU states.

Then after Covid there was a mistaken fear in government of a huge shortage of workers. As others have pointed out, the subsequent surge in migration meant that neither business nor government made the necessary effort to get Brits back to work.

Instead they just shipped in migrants, especially for low-paid work in the care economy.

“Treasury thought the economy grew through immigration,” Rees-Mogg says. “That’s false.” Instead, he believes, the result is often a decline in per capita income. Britain this week just avoided a technical recession by recording 0.1 per cent of economic growth in the last quarter. But it is in a per capita recession, two quarters of declining per capita income. Australia has in recent years experienced per capita recession as well.

Rees-Mogg believes a future Conservative government, if it really wants to take control of immigration even to the extent that Australia has, will have to withdraw from the EHRC and perhaps the Refugee Convention. It will need to repeal big pieces of legislation such as the Equality Act and the Human Rights Act.

Otherwise, he says, you get courts interpreting European and even British law “in ways no normal person would agree with”.

The attraction of immigrants from all over the world is testimony to the success of Western societies. But the inability to control their borders, and to control their immigration systems, is now evidence of shocking Western enfeeblement.

For immigration to be sustained, it needs to be controlled. Voters are determined this will happen. Eventually, even in Britain, they’ll likely find politicians who will do the job. Getting to that point could be needlessly ugly.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout