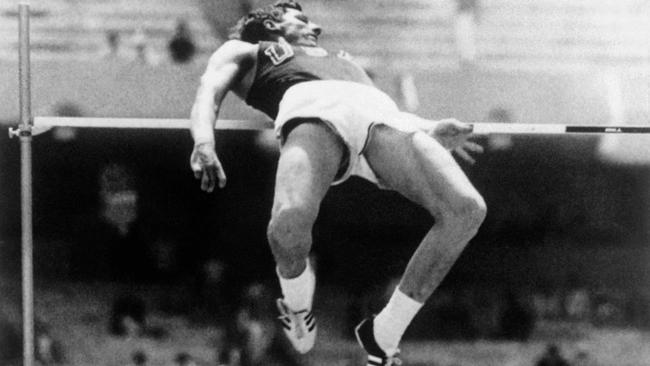

Dick Fosbury changed his sport with a unique high jump style

It was called the Fosbury flop – it won its inventor an Olympic gold medal at Mexico and quickly upended the sport of high jumping.

OBITUARY

Richard Douglas Fosbury Athlete.

Born Portland, Oregon, March 6, 1947; died Salt Lake City, Utah, March 12, aged 76.

Dick Fosbury was perhaps the most influential athlete of all time. He changed his sport.

Rules have been adjusted to end the dominance of sports stars in the past: billiards changed to account for Walter Lindrum’s mastery; soccer’s offside rule was tightened to deal with Newcastle United’s Bill McCracken and his offside trap; golf courses were redesigned to counter Tiger Woods’ invincibility; and several NBA basketball rules were altered to help subdue Wilt Chamberlain’s supremacy.

But the Fosbury flop revolutionised high jumping forever, doing so at the high-altitude 1968 Mexico City Olympics where, at more than 2km up, the thin air already favoured track and field athletes.

There have been three styles of high jumps: with the scissors technique, a jumper put one leg, mostly their right, over the bar with their body and kicked the other up to clear it. This was largely replaced by the straddle in which the athlete raised their body, face down, over the bar to twist around it, one leg following the other.

In primary school, Fosbury used the scissors technique and could clear 3 feet 10 inches (almost 1.17m). He progressed to the straddle but he was still a modest performer. In most schools, the landing pits had been sawdust and wood chips, but about the time Fosbury reconsidered his jumping style raised foam landing pits were more common and essential for the change to come. Notwithstanding this, Fosbury still managed to damage two vertebrae while landing awkwardly.

As a civil engineering student at Oregon State University he perhaps had some understanding of the biomechanical advantages of the radical jumping style he would invent and that bears his name.

Fosbury approached from the left side of the bar curving into it in his last few steps to gain angular momentum. With a twisting leap he passed over the bar backwards, keeping his centre of gravity low and kicking out his legs at the last moment as his hips passed over.

There are almost no rules in high jumping, other than that the jumper must launch themselves from a single foot.

Fosbury experimented with his technique over two years – filming and refining it, speeding up and jumping from farther out – and was soon clearing 6 feet 3 inches (1.91m) and in his first year at university cleared 6 feet 10 inches (2.08m). He won the universities championship in 1968 and then topped other competitions around the US and won his way through the Olympic trials.

Three months out from the Olympics he leapt 7 feet 2.5 inches (2.197m). When Ed Caruthers, who would win silver to Fosbury’s gold in Mexico, first saw his opponent he said: “Oh man, what a nutcase here with this guy.”

On October 20, 1968 – with the crowd chanting “Ole” every time Fosbury approached the bar with his novelty act – he broke the US and Olympic records with a jump of 7 feet 4.25 inches (2.24m). After winning gold he had the bar raised to above the then world record level – 2.29 m (7 feet 6.125 inches), but failed in three shots.

He never held the world record. (Two days earlier, American Bob Beamon violated the stats books with a long jump of 29 feet 2.5 inches (8.9m), breaking the world record by 55cm – still the Olympic record.)

Fosbury’s style took off over the next 12 months. At the 1972 Munich Olympics most of the competitors used the technique and the overwhelming majority of jumpers does to this day.

Fosbury developed the Flop (the name came from a newspaper sub-editor) about the same time that another jumper, Bruce Quande, from Montana, was experimenting with it and whose photograph going over the bar backwards appeared in a local newspaper. But he registered inconsistent results and feared injuring his neck and gave the sport away. The Quande curl remained a secret.

The Fosbury flop continued to break records and on July 27, 1993, Cuba’s Javier Sotomayor cleared 8 feet 0.46 inches (2.45m), a record that stands.

Fosbury coached high jumpers and started an engineering company that designed bike and running trails around Idaho where he lived from 1977. The lymphoma he had suffered 15 years earlier returned a few months ago.

Three years before Swedish DJ and music producer Tim Bergling (who performed as Avicii) took his own life in 2018, he issued the single Broken Arrows with the Zac Brown Band, loosely based on Fosbury turning a flop into a success. It went to No.1 in Europe and reached No.30 in Australia.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout