China ties: Tiger’s roar masks dangerous fragility

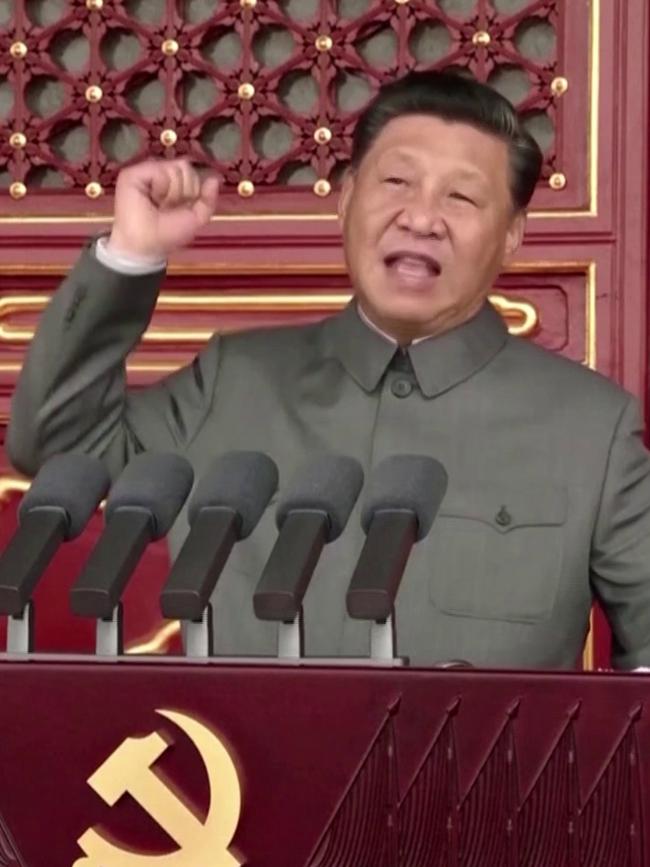

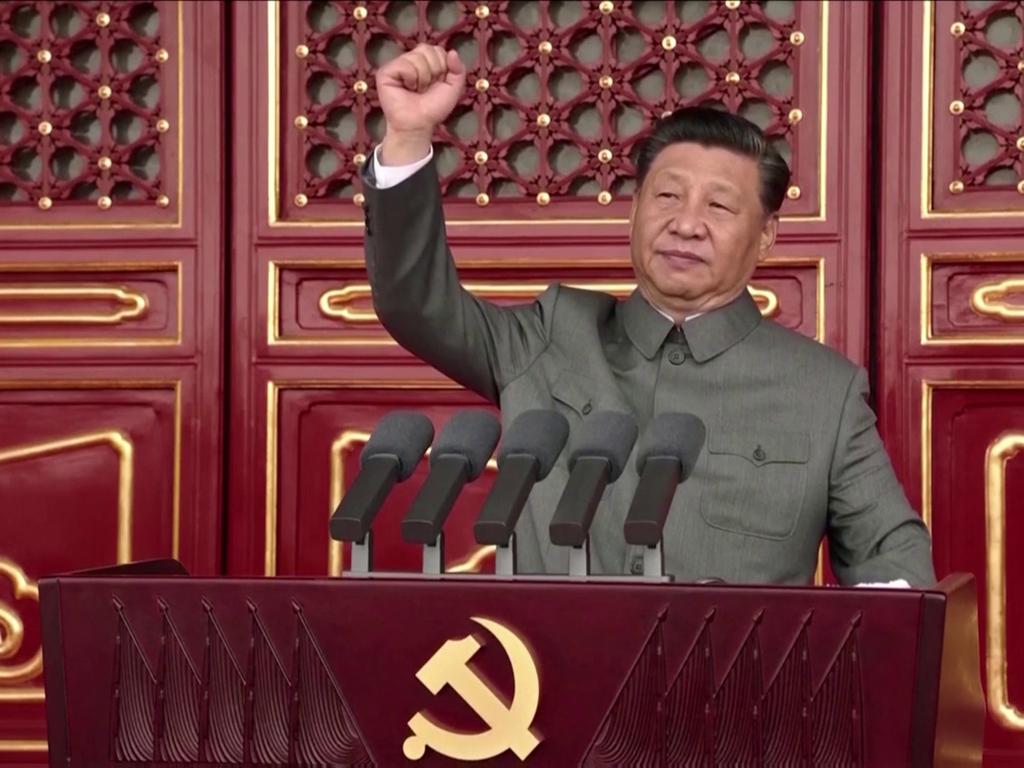

Our Home Affairs secretary copped some flak recently for declaring ‘the drums of war’ were beating in Asia. Xi Jinping himself has just beaten those drums loudly.

Department of Home Affairs secretary Mike Pezzullo copped some flak recently for declaring “the drums of war” were beating in Asia. Xi Jinping himself has just beaten those drums loudly. In his address to the Chinese Communist Party on its centenary this week, he spoke of a “wall of steel” against which the heads of those who opposed China’s rise would be “cracked”. To face him down, we need nerves of steel and very adroit diplomacy.

Our ambassador in Beijing, Graham Fletcher, is the right person for that job in this situation. Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade secretary Frances Adamson was ideal for the situation we thought we were in. Given Xi’s explicit truculence, her replacement will need to be a “wartime consigliere”, someone able to deal with prolonged and dangerous confrontation, multilateral diplomacy and alliance building.

Much of the focus of our diplomacy must be on the weaknesses behind Xi’s strident rhetoric and the alienation it is causing around the world.

A former professor at the Communist Party’s elite training school and a defector to the US, Cai Xia, wrote on the eve of Xi’s speech that the party is more fragile than it wants anyone to see. It is also engaged in a cold war against the US-led order, even as it denounces as “Cold War thinking” any resistance to its ambitions or criticism of its “internal affairs”.

She is far from alone in her analysis. The implications are crucial for our strategic thinking. China is fragile economically, politically and militarily in ways that are not evident to the naked eye and are belied by Xi’s bombastic rhetoric.

Its economic fragility is institutional. Wen Jiabao, then premier of China, declared a decade ago that the rapid growth of China’s economy, while statistically awe-inspiring, was based on foundations that were “unbalanced, unstable and unsustainable”. We worry about our trade dependency on China even as we profit from its growth. We need to think a lot harder about the consequences should it stumble.

There has been a string of deeply informed analyses pointing to these weaknesses during the past decade: Carl Minzner’s End of an Era: How China’s Authoritarian Revival is Undermining Its Rise, George Magnus’s Red Flags: Why Xi’s China is in Jeopardy and William Overholt’s China’s Crisis of Success are among the most authoritative.

None was an anti-China polemic. Each was a mature analysis pointing to real structural flaws in China’s economic institutions that badly need reform if the authentic growth and improvement in the living conditions of the huge population of China is to be sustained.

The forthcoming July-August issue of Foreign Affairs, the prestigious magazine of the US Council on Foreign Relations, is devoted chiefly to the subject “Can China continue to rise?”. Everyone in our government, from the cabinet down to desk-level analysts, should read that issue and reflect on the arguments advanced in it. This is a debate in which we must be very actively engaged.

Second, China’s Leninist political institutions have reached their use-by date. After 1989, party insiders thought they had to transition to authoritarian nationalism on the model of the Guomindang. Xi has created national socialism with Chinese characteristics. His bellicose centenary speech demonstrates this ominously. He declares total unity because that is precisely what is not the case. He practises total dictatorship and threatens total war.

This problem has been pondered for years by first-rate Chinese political scientists in the diaspora, free of the party’s yoke. Liu Xiaobo and other brave dissidents inside China have suffered the brutal weight of that yoke. Liu was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010 for his vision and sacrifice. Dali Yang, Minxin Pei, Jiwei Ci and many others outside China have continued to think through the need for political reform in China – from Western safe havens. Cai is now among them.

Ci (pronounced Sir) gave us a pearl of a book in 2019 titled Democracy in China: The Coming Crisis. It is not a book of wishful thinking. His title deliberately echoes that of the great 19th-century treatise by Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America, which was explanatory and reflective, not a piece of partisan advocacy. Ci is dispassionate and analytical.

From a purely pragmatic point of view, he argues, China must move to democratise its political governance or face a profound legitimation crisis in the near future. Three decades of refusal to take this path have culminated in a regression to outright one-man dictatorship that is exacerbating the underlying problems. Having refused to allow any legitimate opposition or even healthy civil society, the party has built a pressure cooker. If it explodes, there is no fallback position. And it could explode.

We have skin in the game. We need to think about this problem in an informed and concerned way. The Xi dictatorship has turned on us and we must stand firm against it. Yet we confront a dilemma. For if the party persists in its current course, the polity in China might crack open, with consequences that ought to worry us all. Yet if it attempts reform and things come asunder, it also might crack open. Be careful what you wish for is a wise saying.

If it attempts serious reform, we will have to pick our way very nimbly through how that plays out. As Tocqueville wrote in his classic study of the French Revolution, dictatorships are at their most vulnerable when they start to reform. The irony should not be lost on us, though, that a revolutionary regime is so afraid of reform – lest there be, heaven forbid, a revolution.

Third and not least, China’s military and strategic situation is fragile. This will sound paradoxical, given the enormous increase in China’s military capabilities since 1991. We have a justified concern that Xi’s xenophobic, wolf-warrior regime might use force, grey, blue or green, against Taiwan, India, Japan, Vietnam or – in Hugh White’s nightmares – against us. But the “fragility” is more worrisome than the capabilities.

Xi has chosen to antagonise almost all his neighbours at once, with a People’s Liberation Army that has only very recently developed advanced capabilities. He has purged the officer corps and the security forces and assumed unrivalled command of the PLA. Consequently, China’s depth of strategic judgment and capacity to carefully calibrate its moves has been diminished, not enhanced. Unless they are very astute, dictators are prone to make rash decisions. Xi may well do so.

Deng Xiaoping was the boss, but not an outright dictator like Mao Zedong or Xi. Even he made a poor decision, in 1979, to invade Vietnam with a run-down PLA, which then got bloodied by a war-hardened Vietnamese army, fighting on its home turf against the traditional enemy. Xi could make far worse decisions.

When Deng died in 1997, I wrote that our biggest concern might be that he, a Chinese Bismarck, would be replaced by a much less canny figure, endangering China and the rest of us. In fact, the system of collegial and conservative leadership he had set up worked relatively well for 15 years. But it failed to undertake crucial reforms. Then it failed altogether.

Between 1862 and 1888, Otto von Bismarck transformed Germany, as Deng transformed China between 1976 and 1997. In 1888 the young Kaiser Wilhelm II came to the throne. He discarded Bismarck’s careful though ruthless foreign policy, preferring vigorous and rapid expansion to carve out Germany’s place in the sun. He sacked the astute old man and embarked on a foreign policy and arms build-up that culminated in World War I.

Cai and others declare that the 100-year-old party has failed. Yet we might profoundly wish it had not. It has failed despite its 30 years of mercantilist growth, powered by trillions of dollars of foreign direct investment from Taiwan, Japan, South Korea, the US and the EU, open markets for its exports and economic managerialism handled by bankers, bureaucrats and entrepreneurs educated, in countless cases, in the best Western universities.

It has failed because its best strategy would have been to emulate South Korea and Taiwan by getting to middle-income levels, then democratising its political system. It feared to attempt this when it could.

It now faces a precipice, but it is refusing to admit that and is blaming everyone else for its precarious position. Its massive repressive measures, as Ci makes clear, are gravely exacerbating the problem. If it cannot or will not step back from the precipice, it could topple, with grave implications for us all.

In short, China is a much more complex problem for us than any simplistic or introverted analysis of our situation would lead us to imagine. To make matters very much worse, Xi’s regime is not interested in any form of constructive dialogue with us about these problems because it isn’t prepared to admit them or take steps to ameliorate them. What, then, is to be done?

Cai and many in the Chinese diaspora are telling us that we should no longer place trust or hope in the Chinese Communist Party to effect the necessary changes. Brace yourselves, therefore, since the ride could well get very rough.

We have every reason to want sustainable stability, social peace and prosperity in China. We deferred to and courted the party for decades in the hope that the necessary reforms would come with rising standards of living. They haven’t. We are now, all of us, at a crossroads.

What is now going to be necessary is a prolonged, watchful strategy that will do what is necessary to hedge against and head off actual war while countering Xi’s aggressive foreign policy, actively countering his totalitarian propaganda and openly talking up a better and more open political future for the Chinese people. Our economic interest is squarely in seeing China come through this in one piece – well, two or three pieces, anyway.

Would that it hadn’t come to this. But it has. After decades of muddling through, we will have to get very serious and give up idle dreams of making friends with the party or feeling in awe of China’s imperial mystique. The party will need to find a way to remove Xi and identify not a Mikhail Gorbachev but someone like Chiang Ching-kuo, the Guomindang chief who brought the democratic transition to the Republic of China on Taiwan. Such a leader would be an authentic statesman with the abilities and the gravitas to lead China out of its present cul-de-sac and towards genuine, democratic rejuvenation. Come the day.

Paul Monk is the former head of the China desk in the Defence Intelligence Organisation and the author of Thunder from the Silent Zone: Rethinking China (2005) and Dictators and Dangerous Ideas (2018), among other books.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout