Can the Indigenous voice to parliament lead to practical improvements in Indigenous people’s lives?

Rio Tinto’s destruction of ancient Aboriginal rock shelters at Juukan Gorge could have been avoided if the voice was operating, Noel Pearson says. But can it improve lives?

The mining giant’s obliteration of this 46,000-year-old sacred site, once described as a home “to the dawning of humanity”, claimed the scalps of three top Rio executives and led to a federal parliamentary inquiry and federal and state reforms aimed at bolstering protections for Indigenous cultural heritage.

Rio’s blast – aimed at expanding an iron ore mine – had been approved under WA law but was opposed by local traditional owners, the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people, and by archaeologists. Warren Entsch, federal parliament’s northern Australia committee chairman at the time, said the caves’ destruction “was a disaster beyond reckoning” for the traditional owners and wider Indigenous culture, while the PKKP Aboriginal Corporation said a “great sense of sorrow and loss remains for our people”.

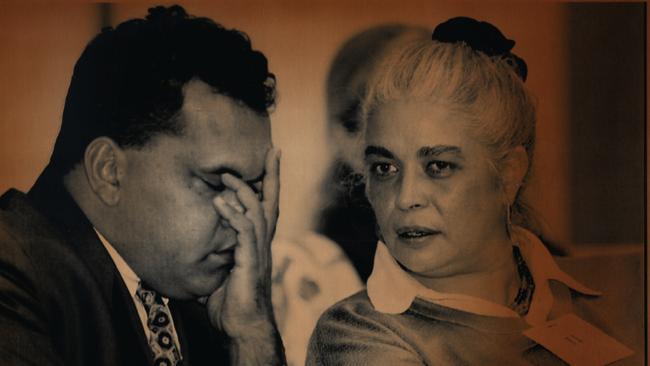

Three years on from the scandal, Cape York Aboriginal leader Noel Pearson says that, had an Indigenous voice to parliament and executive government been operating in 2020, Juukan “could have been saved”.

Pearson says that under an emergency provision of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Protection Act 1984, the remote Pilbara site “should have been protected”, had the Morrison government and federal environment bureaucrats invoked an emergency ministerial power to overrule an earlier WA decision allowing Rio Tinto to proceed.

The prominent Yes campaigner argues the site’s destruction is “the most blatant example” of how a constitutionally enshrined voice to parliament and executive government could lead to tangible change in policy areas ranging from “urgent heritage issues” to alcohol restrictions to addressing the “shitful” education that, he maintains, too many Indigenous children receive at remote schools.

“Recognition and empowerment of people must go together,” he says.

Can the voice lead to practical improvements in Indigenous people’s lives? This is the crucial question that most sharply divides Yes and No campaigners. The former argue this constitutional reform will help close the gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Australians on critical measures such as employment, life expectancy, child safety and education, while the latter maintain that altering the Constitution will be a purely symbolic gesture, accompanied by a new elite bureaucracy.

This issue also divides Indigenous leaders. Aboriginal Yes advocates including Pearson, Marcia Langton, Hannah McGlade and federal Indigenous Affairs Minister Linda Burney argue that the voice, if adopted at the referendum to be held later this year, will lead to policies that will succeed where previous measures have failed – often miserably. Why? Because it will be a permanent body that will give Indigenous communities a more direct say in matters that affect them.

Aboriginal No campaigners such as businessman Nyunggai Warren Mundine and federal opposition Indigenous Australians spokeswoman Jacinta Nampijinpa Price say the voice – which will offer advice on programs and services but will not manage money or deliver services – will be an ineffective, top-down bureaucracy. Says Price: “There are already Indigenous voices across the country telling us what we need to do to help their communities; they’re being ignored by the very people advocating for the voice.”

But Pearson sees the voice’s symbolism and practical goals as inseparable. “Empowerment requires actions on legislation, better policies; let’s try with policies that result in children being effectively taught to read. We don’t do that for many mainstream Australians, let alone Indigenous children,” he said in a recent, powerful address to Rotarians in Queensland.

A co-architect of the voice proposal Australians will vote on at the referendum, Pearson links failures in Aboriginal education to recent outbreaks of youth crime seen in Queensland and Alice Springs. He tells Inquirer: “The kind of education you provide to an Aboriginal child on a remote community is so shitful that they end up not being able to go on with their schooling. And they turn into delinquents and the numbers of these kids start to grow. Then all of a sudden, the problem’s staring you in the face.”

He argues Indigenous schools should focus more on effective literacy and numeracy teaching than on empowering students through culture. “Show me a juvenile delinquent harassing their neighbourhoods and their suburbs and I will show you a primary school child who was never taught to read, who couldn’t succeed in high school, who inevitably fell out and joined the streets,” he said in his Rotary address.

The Cape York leader says “the big drop-off point is the end of primary school when you discover that a child can’t read properly and will never be able to cope in secondary school, so will either be effectively child-minded through secondary school or drop out and become your youth problem.”

However, Price argues the voice proposal endorsed by the Albanese government is so short on detail, it’s hard to see how it will produce tangible benefits in education or other policy areas. She says: “The Prime Minister still refuses to provide Australians with clarity on how his Canberra voice would work, how representatives would be elected and how eligibility would be determined. How can anyone argue that a proposal with so little detail could be beneficial?”

The opposition spokeswoman says when it comes to practical outcomes, “it is not just governments that have failed to close the gap but it is the multimillion-dollar Aboriginal organisations that have been funded to close the gap with little to no accountability. The voice lends itself to duplicating this structure.”

According to official Close the Gap reports, in recent years there have been gains in Indigenous employment, preschool enrolment, infant health and youth detention rates, but rates of suicide, adult incarceration and child removal are worsening.

In April, Price urged a federal takeover of Northern Territory child protection, saying foster parents had told her about cases of Indigenous children being returned to abusers. She made these claims as she restated her opposition to the voice and critics accused her – and Opposition Leader Peter Dutton – of politicising the sensitive issue of Indigenous child abuse.

The senator, a former deputy mayor of Alice Springs, home to often dysfunctional Indigenous town camps, responds: “I will not buy into the premise that raising the profile of an issue as serious as child sexual abuse is politicising it.

“The problem of child sexual abuse is a top priority for me and my constituents, and I will not stop advocating until something is done about it.”

Pearson asks why many practical indicators of Indigenous wellbeing did not significantly improve during the years the Howard, Abbott and Morrison governments were in power, and the 27 years (1974-2001) the Country Liberal Party was in office in the Territory. “What about 27 years of conservative rule (in the Territory), and accompanying failure?” he asks.

Price responds that after coming to power federally and in the Territory, Labor rolled back practical Coalition policies that were working: “The Coalition government was committed to making progress on practical solutions, spending $35m a year on the cashless debit card system and the $3.4bn investment in the Northern Territory’s Stronger Futures Act. When Labor took power, we saw the end of some of those programs that were having a real impact, and now it is some of our most vulnerable communities that are paying the price.”

In his 2022 Boyer lectures, Pearson agreed the left’s “lofty” lifting of alcohol restrictions in the NT and Queensland had adverse consequences for many Indigenous communities. For him, this is a further example of why a permanent voice to parliament and executive government is needed. “Is there a better example of why local communities need a constitutionally guaranteed say in decisions made about them? Those decisions should have been undertaken in true partnership with local communities,” he said.

Pearson says the problem with inconsistent alcohol restrictions does not lie only with Labor governments. He argues it’s an uphill battle for Indigenous leaders to have restrictions enforced and that the voice could change this. “You try and manage alcohol supply in the Northern Territory, Cape York or anywhere in remote Australia, you’ve got to deal with the Australian hotels lobby and the Country Liberal Party, you’ve got to deal with the Labor Party,” he says, adding that it’s the same story with the poker machine industry.

He mentions how Woolworths’ 2021 decision to abandon its plan to open a Darwin Dan Murphy’s megastore “a few hundred metres” from dry Indigenous communities was “a very narrow victory” – Woolworths dropped its proposal only after a backlash from Aboriginal and health groups and an independent review.

Interestingly, while Pearson is a powerful, well-connected advocate for the voice, many of his priorities – among them building stronger Indigenous families, promoting “safe and prideful” homes and balancing individual rights with responsibilities – dovetail neatly with a socially conservative agenda.

This year, the NT and federal governments said they were open to extending the Family Responsibilities Commission Pearson has pioneered in five Cape communities including Hope Vale, where he grew up. Comprising local leaders and elders, the commissioners are legally entitled to put welfare-dependent residents on to compulsory income management following official notifications over child safety, domestic violence, school truancy or tenancy issues.

Pearson has described this welfare quarantine scheme as “revolutionary”, but when asked whether the voice will join the call for it to be expanded, he is cautious. “People have got to take responsibility for their own mob. I take responsibility for people in Cape York,” he says.

In contrast to Pearson’s ambitious reform agenda, businessman Mundine says private sector investment and job creation are the only measures that will lift Indigenous living standards. “As with other people around the world for the last 500 or 600 years, it is only economic development – private commercial businesses, investment, jobs, education and infrastructure – which will make those differences on the ground,” he says. “The track record when it (Indigenous policy) is run from the capital cities or from Canberra, it has failed miserably. Why would you not empower those Indigenous traditional owners and First Nations rather than putting a (regional) bureaucracy on top of that, and then putting a national bureaucracy on top of that?”

He is referring to the voice model proposed in the Indigenous Voice Co-Design Process final report by professors Langton and Tom Calma. Under this model, local and regional voices would be drawn from 35 regions across the nation. These regional voices would engage in two-way dialogue with the national voice’s 24 members, who would represent the states, territories and remote communities.

Mundine is concerned voice members may come between traditional owners and mining and other companies who currently negotiate directly, leading to more negotiations ending up in court.

“Yolngu people represent Yolngu people,” he says. “Bundjalung people represent Bundjalung people. In our culture, they are the only voices that can speak for land. At the moment, people from government and the private sector speak directly to them. So now you’ve got to put into that discussion a regional body? That to me is bizarre. We need to stop putting more structures in place and invest in industry and jobs … There’s no other way forward.”

When we speak, the outspoken No activist is heading to WA to talk to miners and Aboriginal people working in that industry. He says 1000 Aboriginal people are working in his businesses and for the mining, construction and energy companies he is involved with. “Ten per cent of them are in regional and remote Australia. You know the biggest employer of Aboriginal people? The mining industry … the flow-on effect is something like a $4bn economy for Aboriginal people.”

But WA academic and UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues member McGlade says there is a clear link between advocacy and practical change. She says her advocacy to the UN for a separate national action plan on violence affecting Indigenous women helped sway governments in Australia.

In 2016, McGlade and other Indigenous activists “felt strongly that the current plan hadn’t given enough attention to Indigenous women’s issues, including Indigenous women’s experiences in the justice system.

“I went before several UN treaty bodies and UN experts to argue for this, and they agreed and encouraged Australia to adopt a separate national action plan on violence against Indigenous women. And this campaign was taken up by a peak Aboriginal women’s body Djirra and finally the commonwealth.” She and other campaigners also pushed for a council on violence Against Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander women, which was established by the Morrison government, and for Indigenous children’s commissioners in Australia. The latter was a recommendation of the 2002 Gordon inquiry into West Australian government agencies and Indigenous family violence and child abuse, but it had been ignored.

Following McGlade’s pleas to the UN, Victoria became the first state to establish an Aboriginal children’s commissioner, she says, “and they are they are now present in most states”.

An associate professor at Curtin University’s law school, McGlade also has backed Indigenous women who have been jailed for harming their partners but who acted in self-defence.

Despite these successes, she says, “Aboriginal women advocates are too often not supported or heard,” and she says the voice will remedy this. She says it also will help to resolve the “shocking” reality that in 2023, “the gap has been shown to be increasing in terms of incarceration, child removal and suicide … Things are actually getting worse in key areas and (many Indigenous) women and children’s lives are not improving.” Australian Institute of Health and Welfare figures show that from 2017 to 2019, Indigenous women were 27 times likelier than other women to be hospitalised for assault and 7.6 times likelier to be murdered.

As the ABC recently reported, the voice proposal’s “two most controversial words” – executive government – seem innocuous enough on paper. Yet critics argue that permitting the voice to make representations to executive government – government ministers and the departments they oversee – as well as parliament could dramatically slow down the machinery of decision-making across many policy areas. Pearson, however, says this controversy is contrived.

He says if practical outcomes are to be improved, it is crucial the voice can offer advice to executive government as well as parliament. The Juukan failure is “just one of many examples” of this, he says.

“Eighty per cent of the issues we need to tackle are actually bureaucratic, not legislative,” Pearson says. “They’re administrative. Legislation comes along once in a blue moon.

“Policy and programs, that’s where the change needs to happen … You get furious agreement from (Indigenous affairs) ministers about so-called reform and change, commitment, but delivery is where the failure shows up.”

He tells Inquirer that since the demise of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission in 2005, federal bureaucrats maintain that “black fellas plus money equals corruption – that’s a formula; black fellas plus money equals ‘it’ll never work’. Black fellas plus money equals fiefdoms.”

“Massive” church organisations and non-government organisations are the beneficiaries of this assumption he says, meaning that Cape York groups that once provided parenting programs or elder care to their own people no longer exist.

“We don’t feed our old people! Something people are perfectly capable of doing,” Pearson booms down the line from Queensland as he talks about how Meals on Wheels-type services are outsourced to church organisations or NGOs that operate at national scale. “That used to be done by community organisations, with the young people driving the bus and delivering the meals and making the stew,” he says indignantly.

But today, a national tendering system means that “no, we need Anglicare; or we need Uniting Care or we need Catholic Social Services”. He claims service providers affiliated with the Greek Orthodox Church “are in communities where there’s not a f..king Greek person within 1000 miles of the place”.

Even his high-profile organisation, Cape York Partnerships, is not big enough, he says, to tender for a $200m federal parenting program a single provider is meant to roll out nationally.

In the Cape, along with the Family Responsibilities Commission, he has instituted practical reforms including savings accounts for children from welfare-dependent families. Bureaucrats were sceptical this program could succeed, he says, but Coen and Aurukun have each accumulated $1m in parental savings for their children’s future needs. He says welfare recipients voluntarily sign up to the scheme and “we lock the money away” so it can be used when children need books, computers or soccer boots.

This week, the ABC surveyed federal parliament’s 11 Indigenous politicians on the voice proposal. Seven Aboriginal MPs including minister Burney and Greens senator Dorinda Cox support the proposal unequivocally, arguing it will help close the gap. Burney said: “The voice is … about drawing a line on the long history of failed policies and programs in Indigenous affairs. It’s about making sure that the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Australians are heard on the matters that affect them.”

Three Indigenous MPs – Price, the Coalition’s Kerrynne Liddle and independent senator Lidia Thorpe opposed the voice proposal, while independent Tasmanian senator Jacqui Lambie was on the fence, demanding to see more detail. For the left-leaning Thorpe, the voice is “a distraction that has delayed real changes and work towards a treaty”.

Like Mundine, sisters Adele and Cara Peek say job creation is central to improving their people’s lives. Unlike Mundine, they believe the voice will help achieve that goal. The Yawuru-Bunuba women run Make It Happen HQ, a business hub in Broome for aspiring Indigenous entrepreneurs offering everything from hot desks to legal and marketing advice, and they say arguments over the voice have done little to promote the business prowess of First Nations people.

The sisters have offered training to a chef, graphic novelist, justice diversionary and cattle industry workers to help them become self-employed and “generate a viable product”. However, Cara Peek says “the barriers that we face as Indigenous female entrepreneurs in remote Australia are immeasurable, and I think the voice has the potential to the lead the way and make a material difference.”

She argues regional entrepreneurs should have the same access to services and mentoring that city dwellers do, or “our communities are going to be left behind”. And she is optimistic a voice “that cannot be silenced with a mere legislative flick of the pen by the parliament of the day” can make that happen.

In 2020, Rio Tinto’s destruction of irreplaceable archaeological treasures – ancient Aboriginal rock shelters at Juukan Gorge in Western Australia’s Pilbara region – caused international outrage.