‘Bidenomics’ hits the skids as costly policy disasters loom

The US Inflation Reduction and CHIPS Acts are shaping up to be wasteful policy disasters, contributing to a worsening US fiscal situation that could trigger a crisis for whoever wins the presidency in November.

Times have changed. The past few years in particular have witnessed a policy disaster in the world’s biggest economy and, sadly, it’s one other nations, including Australia, appear keen to replicate. Joe Biden’s signature Inflation Reduction Act, which inspired Australia’s soon to be legislated Future Made in Australia Act, is routinely lauded as wise industry-building and climate change policy, but it is shaping up to be a costly disaster.

Passed into law in August 2022, the IRA contained about $US500bn in spending and tax concessions, mainly to spur purchase of electric vehicles and construction of solar and wind power, along with a smattering of minor tax increases. How encouraging the supply of a more expensive form of energy was ever going to reduce inflation boggles the mind. Indeed, for the past few months inflation in the US, as in Australia, has started to rise again.

Even Biden, whose once routine boasts about the virtues of “Bidenomics” have fallen to zero this year, said in August last year he wished “I hadn’t called it that”.

“I can’t think of any mechanism by which it would have brought down inflation to date,” former Obama administration economist Jason Furman told Associated Press last year.

Generous subsidies haven’t prompted an acceleration in the purchase of electric vehicles; quite the opposite as car rental companies sell their stocks and American car yards loudly complain their stocks of EVs are overflowing – even as their prices have fallen.

If the expectations of a surge in solar and wind power installations were to materialise, how are these to be connected to America’s relatively primitive electric grid? The IRA includes precious little funding for unsexy construction and replacement of poles and wires, which ensures the lofty net-zero targets will never be met. The watered-down “Green New Deal” is becoming a dud, which could have been predicted at the outset.

Good economics has long advised against having governments pick winning companies or industries. Their choices tend to be terrible, ultimately failing and leaving taxpayers with an enormous and growing bill.

Last year Goldman Sachs estimated the cost of the IRA would be closer to $US1.2 trillion, almost three times the promised cost. In August last year, Wood Mackenzie, assuming a more insatiable take-up of the IRA’s handouts and subsidies, concluded the actual total cost would be $US2.8 trillion.

If the IRA’s provisions do manage to curb US emissions, it will have come at huge cost to public funds.

Surely the CHIPS and Science Act, Biden’s other big “industry building” reform, is better at least than the IRA? At a mere $US52bn, it includes manufacturing grants, loans and tax credits to largely semiconductor manufacturers to set up plants in the US.

The idea was to make the US less dependent on Taiwan for advanced chips.

As of January, well over a year since applications opened, only two tiny grants had been made for less advanced types of chips. It’s no surprise why, given the act was festooned with ridiculous conditions for applicants designed to pursue totally unrelated agendas.

Applicants must demonstrate they will employ women (who make up about 10 per cent of the US manufacturing workforce), people of colour and even “justice-involved individuals” – that is, those who’ve spent time in jail. They must provide childcare and “include significant investments to create opportunities for Americans from historically underserved communities”.

At least Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo is getting the workforce ready for such demands, recently launching a semiconductor training program funded by the CHIPS Act for historically black colleges to coincide with Black History Month.

No wonder US chip giant Intel is continuing to pursue its new facilities in Poland and Israel. The risk of Russian and Hamas rockets appears preferable to the Democratic Party diversity, equity and inclusion diktats.

Taiwan semiconductor giant TSMC founder Morris Chang warned in 2022 that the act would end up an “expensive exercise in futility”. Its own attempt at building a new plant in Arizona on the back of US subsidies, part of a long-term plan to rake in $US15bn in taxpayer subsidies, has repeatedly stalled.

Even if some plants do ultimately get up and running, they probably would have anyway. The big semiconductor giants were already making record profits and planning to increase their production in the US before the CHIPS Act was passed.

Both these big subsidy programs have contributed to America’s diabolic fiscal situation, which is bound to end badly. US federal public debt, already about $US34.5 trillion ($52.8 trillion), is increasing by about $US1 trillion every 100 days.

This financial year the US is on track to spend about $US870bn on interest, which is equivalent to 17 per cent of tax revenues, the highest since the 1980s. That’s already more than the defence budget, and soon will eclipse even social security as the single biggest government expense.

The US hasn’t run a budget surplus since the tail end of the Clinton presidency in the ’90s and expenses continue to gallop ahead of revenues with no plan to fix either in sight. As a share of GDP, the federal deficit was 6 per cent last year, proportionally about four times the size of Australia’s. Even for the richest, largest economy, that’s not sustainable.

Amid few signs inflation is abating as government economists had predicted, interest rates on US government borrowing are likely to remain near 5 per cent or perhaps even rise, risking a potential fiscal death spiral, the possibility of which receives barely any attention. It’s worse than the mere figures may suggest. Unprecedented central bank money creation during the Covid-19 pandemic has cast doubt on the long-term stability of financial systems, not to mention economic experts who failed comprehensively to predict the return of high inflation.

More and more people are avoiding saving in cash and bank deposits to avoid a sudden collapse in their purchasing power.

Soaring asset prices throughout rich countries (where similar if not quite so bad economic policies have been introduced) could reflect a decline in value of fiat currencies used to buy them as much as a genuine increase in asset values for fundamental reasons. In terms of gold or bitcoin, they haven’t gone up at all.

The lesson of the past few years for politicians should have been caution, but instead the pandemic has fuelled hubris and a return to artificially complex, vast subsidy schemes that would make the planners of generations ago proud.

Whoever wins the presidential election in November could well inherit an economic disaster. Far from cutting taxes again, as he did in his first term, a re-elected Donald Trump might have to increase them significantly to restore faith in US economic policy.

That would be an unwise policy for Australia to emulate, too, given our differing circumstances. If we must copy a US policy could we just index the income tax thresholds to the consumer price index?

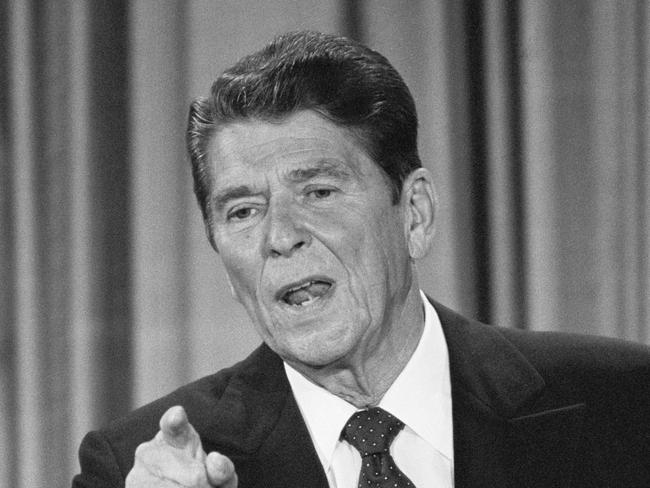

Once upon a time the US offered policy examples for other nations to follow. In the 1980s Ronald Reagan radically reformed the US income tax system, lowering rates and broadening bases. In the ’90s Bill Clinton enacted tough-love reforms to welfare payments in a successful bid to boost workforce participation.