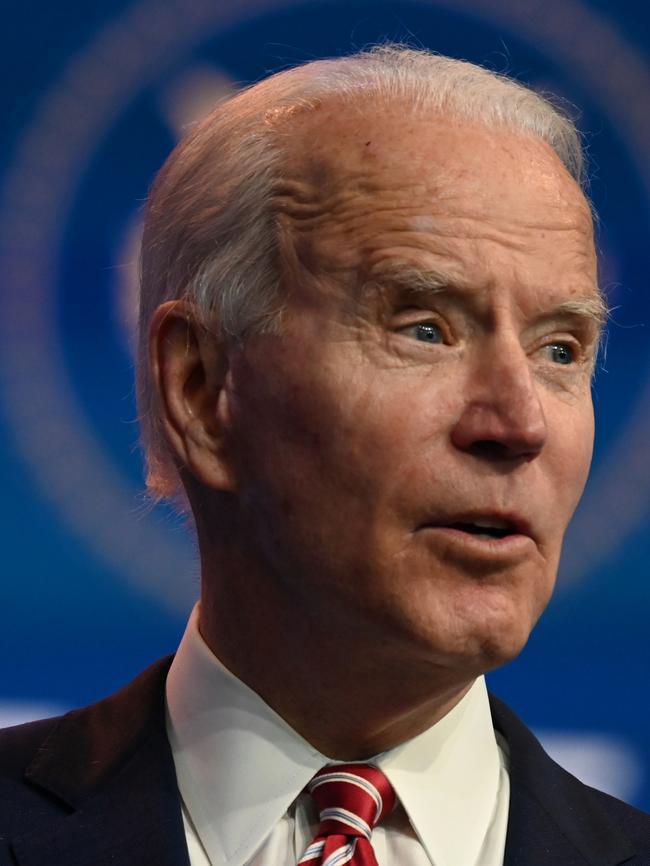

Biden or Trump US trade isolationism a concern in Canberra

Biden has reinforced the US’s historic shift on trade, which now prioritises US national security through an industrial policy-led approach. Biden maintained Trump-era tariffs on imported Chinese goods and expanded export controls and investment screening to limit Beijing’s access to US technology and companies. Moreover, both Biden and Trump have shown little interest in American leadership through global trade institutions such as the World Trade Organisation.

This transformation in US trade policy came as a surprise to many – the US having championed economic integration and backed rule-setting bodies since the end of WWII. But, seen in the historical context of the “China shock” – where Chinese exports to the US exploded, the 2007-08 global financial crisis, and China’s unfair trade practices over decades – this US policy shift may in fact have been years in the making.

Another major factor driving US trade policy is domestic politics. The gains of globalisation were not evenly distributed, either within or across countries. In the US, free trade is blamed by the right for the loss of manufacturing jobs and growing inequality, and by the left for driving lower standards and higher pollution. Right now, no US politician is served by championing free trade, and that’s unfortunate for Australia.

In practice, it has meant that Biden cannot do a multilateral free-trade agreement with countries in our Indo-Pacific region. Australia already has a bilateral US FTA but a US-led regional FTA would play strongly to Canberra’s interests. The capacity of such an agreement to offer the carrot of US market access in exchange for members raising their standards and adhering to robust trade rules would serve the dual purposes of regional economic development and liberal democratic norm setting.

The best Biden can currently offer is the Indo-Pacific Economic Framework, a 14-member pact including major regional economies as well as developing ones. IPEF does not include US market access but addresses non-tariff barriers to trade. So far, its members have agreed on terms relating to supply chains, transitioning to clean energy, and anti-corruption and tax transparency.

The IPEF is Biden’s alternative regional deal after Trump withdrew from the Trans-Pacific Partnership. Even though the IPEF is not an FTA, it’s better than nothing, and nothing – no IPEF – is what Trump promises. Last year Trump said that, if re-elected, “the Biden plan for ‘TPP Two’ will be dead on day one”.

The other US trend Australia and others wish was not happening is its retreat from rule-making bodies such as the WTO. The WTO has been ineffective in many ways for decades, but it still works to Australia’s benefit. Australia successfully used the WTO arbitration mechanism to pressure China over its barley and wine tariffs, and both exports are now back on the tables of Chinese consumers. Under both Trump and Biden, the US has blocked appointments to the WTO Appellate Body. As such, the dispute arbitration system has been paralysed. For a trade-exposed country such as Australia, strong global trade bodies are vital. We will instead have to work with like-minded partners – Japan, Korea, the EU, UK and others – to reinforce this institution, despite its shortcomings.

Biden is more predictable than Trump and he’s more willing to co-operate with trusted allies and partners. That includes his openness to “friendshoring” – investing in new supply chains in allied nations to reduce US reliance on China – and dedicated carve-outs for Australia in major US industrial policy. Under Biden, Australia is being considered a US “domestic source” of production, meaning Australian companies can access US subsidies for key sectors such as critical minerals.

In contrast, if Trump is re-elected he promises to go back to the tariff well, only bigger and broader. When Trump was president, Australia evaded steel and aluminium tariffs largely thanks to support from US officials working under Trump. This time, Trump has said he will impose a 10 per cent tariff on everybody in the world and triple tariffs on China from a current average of around 19 per cent to 60 per cent. He could be bluffing but, bluffing or not, his unpredictability and isolationism would make Australia’s trade relationship with the US harder to navigate.

The US pivot away from free trade and related institutions presents Australia with a challenging new global trade outlook it must now confront. Whoever wins in November, Australia will have to protect its interests by “selling” the US on the positive story of Australia-US trade relations and looking for areas of common ground. Luckily, the critical minerals and rare earths that lie beneath Australia’s crust hold the key to the clean-energy transition, critical technology and defence capabilities – meaning Australia has the natural endowments necessary to capture US investment and co-operation, and ride this new wave of global economic upheaval.

Hayley Channer is director of economic security at the US Studies Centre at the University of Sydney.

Joe Biden and Donald Trump are different in many ways but on trade they are much closer than many appreciate. No matter who wins the US presidential election in November, the era of blanket US support for free trade and global trade institutions is over, and that has major implications for Australia.