Anthony Albanese straddles the factional divide and keeps ambitious leadership rivals at bay

The former Hard Left radical is now effectively leader of the NSW Right, a twist in the tale of successful mathematics and manoeuvring that explains Anthony Albanese’s reigning authority.

No one with a long memory of how Labor’s NSW Right faction works can recall that it was ever told what to do – from the outside – and then complied.

When Labor “mates” such as Graham Richardson and Paul Keating called the shots, the NSW Right was dominant, fierce, a seemingly unstoppable machine.

The faction’s power didn’t end with the ability to pick Labor candidates and ministers from the most populous state.

With its election-winning formula of pragmatic politics, the NSW Right guided Labor at a state level and nationally as well. It could make, or break, party leaders. Its numbers were used to block the ALP Left at every opportunity.

The decline of the NSW Right was finally confirmed this week when the faction followed orders from the Victorian ALP’s Right, forcing out NSW MP Ed Husic as a cabinet minister in the Albanese government.

On the face of it, Husic’s exit was simply a numbers game because the Victorian Right, led by Deputy Prime Minister Richard Marles, made it crystal clear that the NSW Right was over-represented in the ministry compared with Victoria, and one of its own needed to go.

Marles also had dispatched Mark Dreyfus in his state as attorney-general – supposedly to refresh ministerial ranks.

But Husic’s exit from cabinet was a direct hit at the NSW Right. It also enabled Albanese to promote Tim Ayres, one of his closest allies in the NSW ALP Left.

A Keating protest against Husic’s removal fell on deaf ears. But more to the point, what did Husic’s NSW Right mates do to save him? Faction ministers Tony Burke, Chris Bowen and Jason Clare applied pressure on Marles – but the response was a firm “no”.

Richardson tells Inquirer that tough calls need to be made. But he also argues the NSW Right and Albanese too “should have found a way to keep Husic”. He adds: “I would have. There’s always a way.”

As one of few senior ALP figures prepared to speak on the record for this article, Richardson has a simple reason why NSW Right ministerial colleagues Burke, Bowen and Clare did not push harder to help Husic. “Selfish,” he says. It was Husic or one of them.

The NSW Right’s declining influence in the Labor Party is about shifting numbers, clashing personalities and a history of office dysfunction at party HQ in Sydney’s Sussex Street.

But the bigger story focuses on how Albanese has successfully moved to capitalise on disunity and weakness in the NSW Right while also benefiting from the ALP Left’s growing strength at a national level. While it may seem far-fetched at first, high-level party observers familiar with the mathematics and manoeuvring suggest the real de facto leader of the NSW Right is now Albanese.

How could that be? Albanese already wears another hat as the party’s most senior figure in the NSW ALP Left and ALP left faction nationally.

Before Albanese was first elected to federal parliament as a Labor MP from Sydney’s inner west in 1996, he was the NSW Left faction’s man in Sussex Street party HQ, employed full time as assistant party secretary. It was a job without any real power except within Albanese’s faction because the dominant NSW Right leadership treated Albanese’s position as a token to the Left.

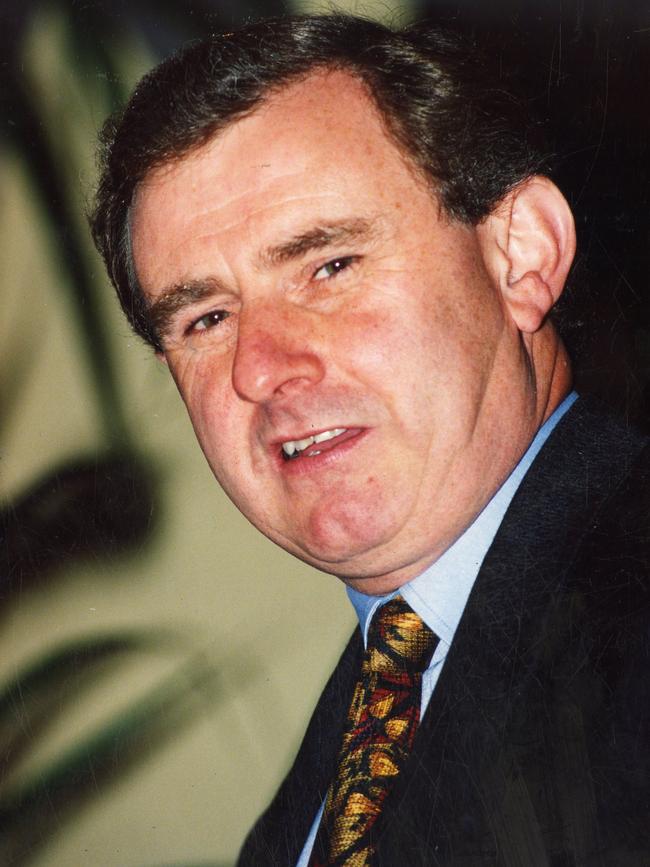

Albanese was then a “Hard Left” angry young radical and experienced first-hand the Left’s isolation inside NSW Right-dominated HQ. John Della Bosca was the NSW Right’s anointed party secretary, respected as an election tactician but also a factionally tough player in the mould of his predecessor Richardson and the legendary kingmaker John Ducker.

Once in parliament, Albanese could not have foreseen he would become federal party leader, let alone prime minister. It seemed an impossibility considering the NSW Right’s power.

Albanese continued to wear his Hard Left credentials like a badge – but he was gradually brought in from the cold. As an opposition Labor MP, he became more friendly in 2002 with prominent NSW Right figures and others from interstate. Along with so-called roosters Wayne Swan and Stephen Smith, plus Stephen Conroy, Kevin Rudd and Leo McLeay, Albanese was a member of a cross-factional group in Canberra nicknamed the “ABC Club” (Anyone But Crean).

After Labor’s 2001 election loss, Simon Crean had replaced Kim Beazley as leader. Albanese and the others concluded Labor could not win with Crean against John Howard in 2004. They campaigned behind the scenes to restore Beazley.

Albanese’s role in the ABC Club, while still loyal to the ALP Left, demonstrated that he’d become foremost a pragmatist who wanted Labor to win. In this instance, the NSW Right split, Mark Latham was installed as leader and Labor lost the 2004 election.

But Albanese had straddled the factional divide. Relationships deepened. He became an enduring backer of Rudd and his politics mellowed as he accepted that shifting to the centre was necessary for Labor’s popular appeal after years of opposition wilderness under Howard. When the NSW Right ousted Rudd as prime minister in 2010, with help from Bill Shorten in Victoria and Don Farrell in South Australia, Albanese and Rudd stayed close.

Rudd’s brief return as prime minister in 2013, after Julia Gillard was dumped, was critical to Albanese’s further rise: he had been a senior Labor minister since 2007 but Rudd elevated him to leadership material as deputy prime minister. When Rudd-Labor lost the 2013 election, as expected, Albanese was suddenly in contention for the leadership in a two-horse race against Shorten. Albanese had already broadened his image, dispensing with past radicalism. Later, he would even have a Sydney beer named after him.

Albanese was bitter after he lost to Shorten because of some grievances about the party’s voting process. He also fell out with the highly popular Tanya Plibersek from his own NSW Left faction, angry that she’d agreed to stand as Shorten’s running mate and had possibly improved Shorten’s prospects. The frostiness between Albanese and Plibersek never let up but Albanese used the next two terms in opposition under Shorten’s leadership to forge closer links with influential NSW Right MPs Burke and Bowen.

When Labor lost the 2019 election, and Shorten stepped down, the NSW Right made the final step, previously unthinkable: Albanese became the NSW Right’s candidate for leader because it lacked one. Marles from the Victorian Right became Albanese’s party deputy. But Marles was already a significant Albanese ally: they’d become close during Shorten’s latter leadership years. Marles was Albanese’s loyal point man inside the Victorian Right.

As matters stand, Burke remains Albanese’s closest friend in the NSW Right. Albanese seems less enamoured with Bowen, possibly because of Bowen’s role in Labor’s 2019 defeat.

Those who know Albanese well predict he will remain Labor Prime Minister for as long as he can, even having a go at Bob Hawke’s record. At the very least, Albanese wants to make Labor the natural party of government in Australia, and Labor’s unprecedented 93-seat election victory a fortnight ago opens the door to that possibility. While Albanese’s authority now appears supreme, hanging on to the mantle could depend on harnessing the NSW Right and keeping ambitious leadership rivals beneath him at bay.

Burke is Albanese’s loyal NSW Right point man, influential in the faction but also useful to block other leadership contenders, especially Queensland’s Jim Chalmers. If Albanese did support a successor one day, it is thought to be Burke.

Marles has leadership ambitions as well, which could present Albanese with a conundrum.

A further indication of Albanese’s grip on the NSW Right is the internal party claim, if true, that Husic’s exit was a deliberate move: Albanese wanted Husic out, leaving others to do the deed, after Husic had stood up to him a few times and allegedly leaked cabinet information.

Meanwhile, Albanese has personally interfered with NSW Right and other party preselections, attracting criticism that a prime minister should stick to governing.

The prime case ahead of the election involved retiring Labor left-wing MP Linda Burney in the Sydney seat of Barton. The NSW Right had fully expected Burney’s seat to go back to them – because Barton was previously a Right faction seat. NSW Right candidate Sam Crosby had moved to Barton and seemed to be waiting for Burney’s retirement after a failed attempt to win Reid in Sydney’s inner west at the 2019 election.

Instead, Albanese intervened, insisting Barton stay with the Left. The matter was referred to the ALP’s national executive with Albanese using his casting vote to pick his preferred ALP Left candidate, Ash Ambihaipahar. She became the MP for Barton two weeks ago. It is chalked up as another loss to the NSW Right on orders from Albo the faction supremo.

As senior Labor figures correctly point out, the NSW Right’s majority numbers inside the state party have largely held up. The NSW Right still has more numbers than the Left at NSW party conferences and on the ruling state administrative committee, thanks to four key right-wing unions. In state politics, Labor Premier Chris Minns and most of his senior ministers are from the NSW Right.

But Albanese seems not to care about the details of state politics. He is focused most on shoring up his position nationally where the ALP, state by state, has fallen to the ALP Left, exposing a weakened NSW Right, now apparently Albanese’s servant.

For much of the past 17 years, the NSW Right’s management of party HQ has been an organisational mess with disunity creating a leadership vacuum. No wonder Albanese, the ultimate numbers man, took advantage of the situation.

After Richardson left as the NSW Right’s party secretary for a Senate spot in 1983 came Stephen Loosley, Della Bosca, Eric Roozendaal, Mark Arbib and Karl Bitar.

Bitar, who left in 2008, was the last party boss until recently to provide stability and clear direction. Afterwards, party head office was a revolving door of office holders. Matt Thistlethwaite held the job briefly. He left for a seat in parliament after being pushed out by the ruthless Sam Dastyari, who left the party job as quickly as he could for the Senate, only to self-implode there and leave the NSW ALP branch in a lot of strife over his connection to a Chinese party donor.

Jamie Clements took over, hoping to restore the Richardson glory days, but he also self-imploded, this time over office infighting and a sex scandal. “Boss Lady” Kaila Murnain replaced Clements. She was overwhelmed by a donations corruption scandal and quit.

Bob Nanva came in from the outside to restore stability, reverting to Della Bosca’s credo that the best political machine was a quiet one. Nanva’s main blunder was parachuting former NSW premier Kristina Keneally into a safe western Sydney seat in 2022. Labor won the election but lost the seat. Nanva didn’t last long, finding a safe seat for himself in the NSW upper house, where he sits today.

Dom Ofner, an experienced political operative, and the NSW Right’s man in head office since 2023, has tried hard to be a healer and achieve consensus across the factions. He now has two election successes under his belt – one state and one federal – but seems reluctant to reassert the NSW Right’s past dominance as he assists Albanese’s leadership.

Interestingly, the connections between Ofner in NSW Right HQ and Albanese in Canberra have been more than a phone call here or there. Ofner’s wife, Phoebe Drake, has worked as an adviser to Albanese. Skye Laris, the wife of Albanese’s close NSW Right mate Burke, works in Albanese’s office as a senior policy adviser.

Some internal party critics claim the biggest problem facing the NSW Right is its failure to address renewal. The next NSW Right cab off the rank for a ministerial vacancy in Albanese’s cabinet is almost certainly Andrew Charlton, elected to the seat of Parramatta in 2022.

Many Labor figures use the same word – “impressive” – to describe Charlton after meeting him. Some rate him as leadership material and say he could be the NSW Right’s path to restored glory one day.

In the meantime, Charlton is Albanese’s cabinet secretary, already on the inside and on the way up. Which would suit Albanese: another name in the leadership mix, circling each other, but not Albanese, for the distant future.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout