Reserve Bank is coming to the rescue now that inflation is back in the zone

As inflation falls and global trade stalls because of Trump’s tariff chaos, it’s time for the Reserve Bank to get back to normal settings.

Australia’s material living standards have not grown during the past six years, constricted in the wake of Covid-19’s traumas by higher inflation, taxes and interest rates.

Reserve Bank governor Michele Bullock and her monetary avengers are coming to the rescue on the home front.

With underlying inflation easing, the RBA’s monetary policy board is expected to trim official interest rates on Tuesday, giving borrowers more breathing space. It will be the second cut in a clamorous year. Some analysts claim officials are behind the play and need to get a move on.

Already 2025 is looking as if it will offer policymakers neither rest nor relaxation as they try to get their bearings amid the policy unpredictability out of the White House. The challenge remains: to see off inflation without crashing the economy.

Donald Trump’s tariff hyperactivity disorder means the risks have changed; weaker growth is worrying central bankers more than the likelihood of a resurgence in inflation. In the US, Federal Reserve chairman Jerome Powell, a magnet for the ire of the commander in chief, is concerned about both.

“If the large increases in tariffs that have been announced are sustained, they’re likely to generate a rise in inflation, a slowdown in economic growth, and an increase in unemployment,” Powell told reporters after the Fed kept its policy rate steady last week.

What a trifecta of woe. The global scene is impossible to predict. An index of economic policy uncertainty developed by Stanford economist Steven Davis and two colleagues hit a record high in May, going beyond the levels reached in the global financial crisis and the Covid-19 pandemic.

The US President’s deal-making with China, Britain and others, and constant resetting of the game clock, is likely to keep roiling markets, which first put their money on worst-case scenarios and then immediately changed their bets to blue skies. In the real economy, when the (bull) dust settles, the rise in trade barriers will lead to lower growth in the US and China, and the rest of the world.

Economists are trimming their forecasts for Australian GDP growth to around 2 per cent in 2025; bland but better than previous years and, given the peak in migration is behind us, a little ahead of population growth.

Australians were the biggest losers among prosperous nations in 2024, with a 1.8 per cent fall in real household disposable income per capita; that came after a record 5.1 per cent plunge in 2023. While our material living standards have stagnated since December 2019, they’ve increased by 8.6 per cent in the US, and 9.3 per cent across the OECD.

Last July’s tax cuts continue to be saved rather than spent, but more moderate growth in living costs will help. A reduction in borrowing costs will improve family budgets. For instance, on an average new home loan of around $650,000, a quarter-point cut to mortgage rates will reduce required repayments by just over $100 a month.

The RBA will keep loosening its monetary setting because the data justifies more interest rate cuts: core inflation is settling into its 2 to 3 per cent target zone and the jobs market is, it seems, less likely to generate wage outcomes that would rekindle price pressure.

We got news on both fronts this week that are in the ballpark of the central bank’s economic forecasts (which will be updated on Tuesday). The economy added almost 90,000 jobs in April and the unemployment rate was steady at 4.1 per cent. For the past 17 months, the trend jobless rate has been stuck in a narrow band, with a floor of 3.9 per cent.

Even though the monthly labour force numbers have been volatile, the latest jump in employment surprised economists. “This will continue to be an evolving judgment as we receive new data, but we can be reasonably confident that the overall labour market remains in solid health,” Westpac economist Ryan Wells said.

Whoever won the May 3 election was always going to ride the down escalator of an RBA cash rate easing, just as the winner in 2022 was doomed to bear the full force of its aggressive tightening of a dozen post-poll hikes across 18 months to fight inflation.

This may surprise you, but apparently a pay increase was on the ballot a fortnight ago. Who among the nation’s 14.6 million workers wouldn’t support that? Jim Chalmers said this week that “Australians voted for higher wages at the election” as he welcomed official statistics that showed the wage price index rising by 3.4 per cent in the year to March, a full percentage point above growth in headline consumer prices.

On this measure, real wages have increased for six straight quarters. According to the Treasurer, “It is the only time since records began that the unemployment rate has been in the low 4s concurrently with headline and underlying inflation in the RBA’s target band.”

Naturally there’s a fiscal impulse at play, from Canberra and the provinces, keeping the economy ticking over. But it’s also pushing up the public debt burden and all that comes with that, such as attracting the attention of the global credit watchers. Borrowing may become more expensive for everyone if governments don’t get on top of their budgets.

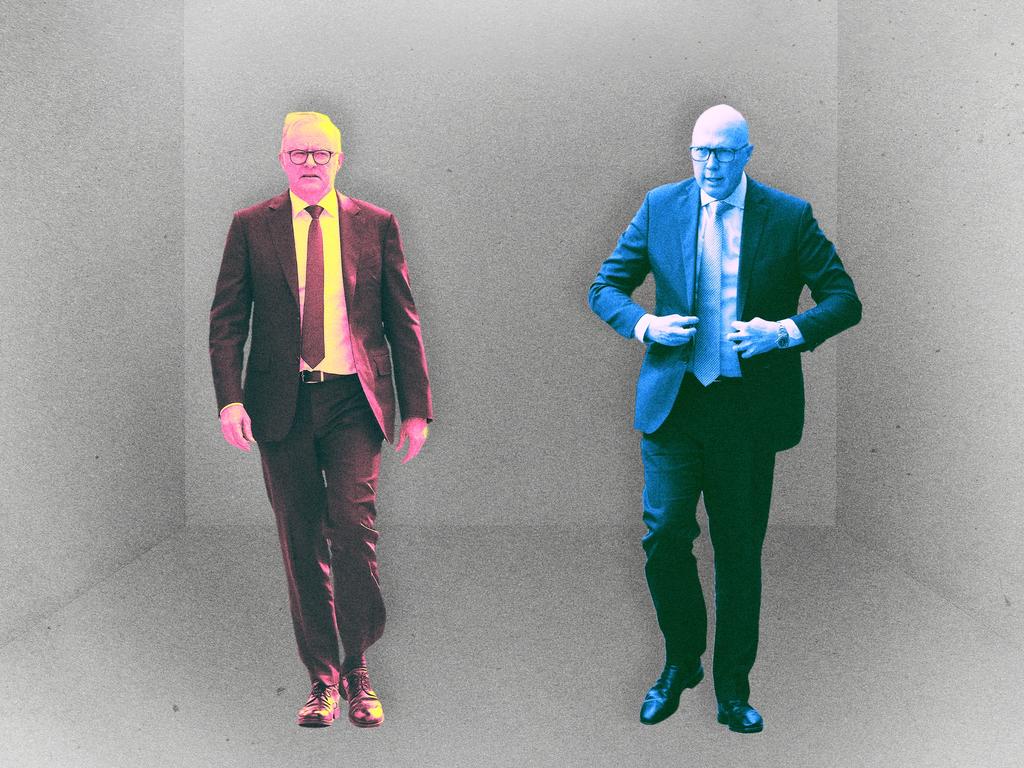

Anthony Albanese argues he is tweaking economic management so that it rebalances growth. He hopes the private sector, namely household spending and business investment, takes the reins and the jobless rate does not stray too far above its current level.

In truth, this “soft landing” is in the hands of the RBA board. Right now, consumer and investor confidence is low; the Trump-generated trade chaos means corporate expansion plans and major household purchases get put on hold. Lower borrowing costs and a steady rise in property prices, however, will improve sentiment.

With inflation tracking down in line with forecasts, Commonwealth Bank head of Australian economics Gareth Aird sees the RBA easing interest rates gradually, with three more 0.25 percentage point cuts this year. “Given the good news on inflation and still soft growth in private demand, there is no need to have monetary policy at such a restrictive setting,” he tells Inquirer.

Aird says a fourth cut is not out of the question if the economy slows more than anticipated. That would bring the cash rate (now at 4.1 per cent) to 3.1 per cent, around the so-called nominal neutral rate, where it is neither stimulatory nor restrictive to economic activity. In estimating where that point is, he puts significant emphasis on debt serviceability.

Mortgage repayments as a share of household disposable income are at a record high of 11 per cent. A cash rate closer to 3 per cent, says Aird, is consistent with a debt serviceability ratio of around 8 per cent, which was the 10-year average before the pandemic.

But when the RBA meets on Monday and Tuesday there could also be an element of taking out insurance as the global growth outlook worsens. Will the RBA be bolder and try to get ahead of the game? Is it already behind the play given the “closing of wallets” by shoppers, National Australia Bank group chief economist Sally Auld asks.

Auld says the RBA would have cut, rather than held, the cash rate at its meeting almost seven weeks ago had it seen the detail of Trump’s “Liberation Day” tariffs and the ensuing turmoil. “Maybe this week’s deal with China has taken out some of the international risks, but we’re not going back to a better world,” she tells Inquirer.

Consumer spending is weak and will be a drag on GDP when March quarter national accounts are published in the first week of June. Auld argues the RBA will need to take monetary policy to a more neutral setting relatively quickly, arguing the central bank needs to slash the cash rate by a full percentage point by August.

That’s a more aggressive easing cycle than the consensus view. “Restrictive monetary policy is not the right setting,” Auld says, while acknowledging the difficulty of making forecasts and policy moves in this new order “where the ground keeps shifting”.

Yet in a political sense it’s business as usual for the central bank and financial markets: no regime change in the federal capital. We’ll see the same tendencies towards borrowing money to spend big on social services, higher wages in the care sector, industry assistance and the energy transition.

The missing ingredient in recovery is productivity growth; stagnation in output per hour worked has held back growth in the size of our economy, which has been pumped up at different times across the past two decades by migration-driven high population growth. During the population boom in 2023 and 2024, we recorded seven straight quarterly falls in per capita GDP.

According to the OECD, US GDP per capita has grown by 25 per cent since the start of 2007, compared with 15 per cent in Australia and the 20 per cent average for the organisation’s 38-member nations across that period. The difference is down to productivity growth. We’ve lost ground on the US since 2018 and among rich nations more broadly in the post-pandemic era.

It doesn’t matter if we vote for higher wages (and it’s a near 100 per cent primary I suspect). Or if the Fair Work Commission grants award rate rises above inflation. Or whatever the Prime Minister claims about the drivers of wage growth. The curse of income stagnation will remain until we improve our productivity performance.

Because Bullock and her colleagues understand that without a lift in productivity, the inevitable rising unit cost of labour is inflationary. Cost growth gets baked in, above-target inflation returns and rates have to rise. It’s the law. And then we’re back in the slow lane, bottom of the class, the biggest losers, and no rescue in sight until the fever breaks.