Fact is, the national curriculum has done nothing but dumb down education in Australia

Barely half of all students are proficient in maths, science and reading. Could it have anything to do with a national curriculum where Indigenous dance, storytelling and basket-weaving are included in maths classes?

Anthony Albanese talks often about his humble beginnings. A boy raised by a single mother in public housing, educated in public schools, became Prime Minister. The difference today is Australia’s public education system is failing our children. Barely half of all students are proficient in maths, science and reading. Could it have anything to do with a national curriculum where Indigenous dance, storytelling and basket-weaving are included in maths classes?

It is a giveaway sign. But the problem is far deeper. Decades of anti-intellectual fashions filling a national curriculum that fails to help teachers educate students, let alone robust measures to track their progress before they move on to the next year.

This week federal Education Minister Jason Clare announced a suite of reforms, including the planned review of the national curriculum in 2027.

Why the wait? Every year Australian students are falling behind. The most recent OECD Program for International Student Assessment revealed that barely 12 per cent of Australian students performed at high levels in maths, compared with 41 per cent of students in Singapore, while 26 per cent of Australians were low performers, compared with only 8 per cent of Singaporean students.

The opposition’s plan was for a fast-track review to be completed by the end of the year. Maybe that was too fast, but Clare’s timetable is certainly too slow.

Once he gets cracking, the question will be whether the Labor Education Minister can do what previous Liberal education ministers failed to do – fix public school education so kids, especially the most disadvantaged, get the best shot at life.

Education reform is a political football. During the election, when former opposition leader Peter Dutton spoke about reviewing the flawed national curriculum, the Prime Minister shot back that the current curriculum, signed off by the Morrison government in 2022, “is the Liberal Party’s curriculum”.

Those are the words of a political warrior, not a leader concerned about reforming education.

It’s true the last review was done when Scott Morrison was prime minister. Succeeding Liberal education ministers Dan Tehan and Alan Tudge were in charge.

But the story is more complicated. The 2022 redrafted national curriculum is the flawed work of every state, territory and federal education minister, Liberal and Labor – along with the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority.

But Albanese’s broadside about the “Liberal Party’s national curriculum” was enough to scare Dutton. He – or his office – effectively shelved proposed reforms from opposition education spokeswoman Sarah Henderson. Earlier this year, Henderson revealed 2451 lesson “elaborations” about the so-called three cross-curriculum priorities in the national curriculum – Indigenous dance, storytelling and basket-weaving in maths among them.

The cross-curriculum project sets down three priority areas – Australia’s engagement with Asia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander histories and cultures, and sustainability – to be included in every subject from maths to science, English to humanities, social science, physical education and so on. Why sustainability or the other “priorities” are more important than learning how to read or multiply is not made clear. It’s a safe bet this is an evidence-free project.

Now it falls to Clare to do what conservative governments failed to do: knock heads together, clean up the process, then produce a world-class, clear and focused curriculum that helps teachers in the classroom produce high-performing students.

Fiona Mueller was appointed director of curriculum at ACARA in 2016, soon after the first national curriculum was finalised.

The former teacher, education expert and public policy researcher says Clare will need to understand where earlier curriculum reviews went wrong.

The terms of reference signed off by then Liberal education minister Tehan sounded like someone was about to tidy up a pantry. Reviewers were tasked with “refining, realigning and decluttering” the curriculum within its existing structure. That “didn’t cut it”, says Mueller. The vague, lowbrow terms of reference reflected the deeper problem. “There is no intellectually rigorous basis for decisions about Australian school education broadly or the curriculum in particular,” Mueller says.

“Education policy is purely utilitarian, reactive rather than objective or philosophically and intellectually ambitious for our students and teachers and the nation. It’s almost impossible to find any evidence to support the curriculum design.

“For decades, Australian education authorities and their academic influencers have adopted anti-intellectual methodologies without doing the due diligence to make the case for reforms and ensure a sound balance between traditional and new approaches.”

The parameters for the last curriculum review were dictated by the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration signed in December 2019 by every state, territory and federal education minister. It contains two passing references to literacy and numeracy. Both the terms of reference and the Alice Springs Declaration mandated that cross-curriculum priorities would remain in all subjects.

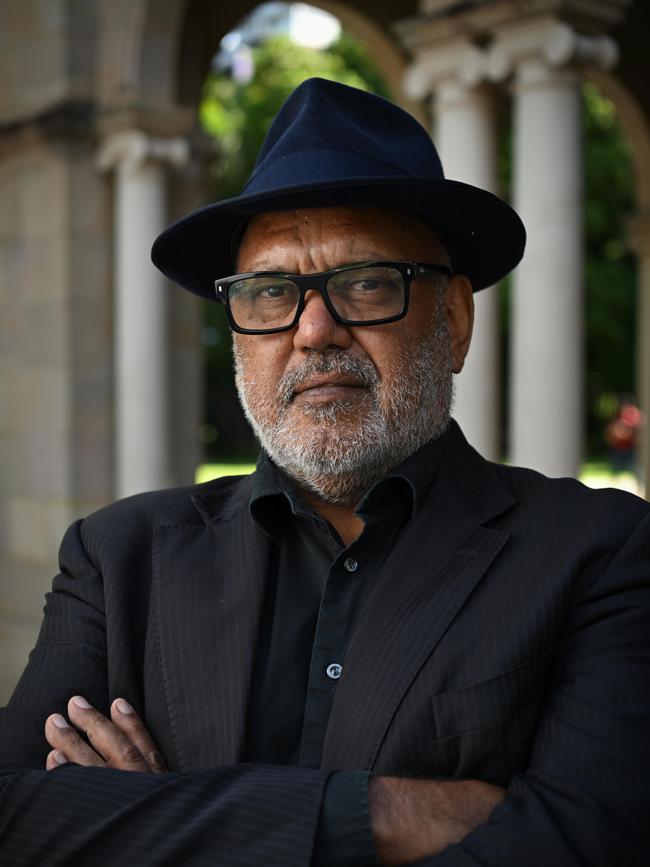

It’s good news that Noel Pearson has recently given educators and politicians his imprimatur to remove cross-curriculum teaching of Indigenous issues. It should be stand-alone, he says.

But common sense should have prevailed long ago.

Similarly, when Clare said this week that the “phonics wars” were over, that was not a cause for celebration. It has taken more than 20 years for a battle over reading to be settled in favour of the evidence that explicit instruction of phonics is the most effective way to teach kids how to read.

Mueller says the “unmistakeable rehabilitation and rebadging of traditional practices … is an unforgivable admission that evidence has not, in fact, been at the heart of education policy for many years.

“Yet there will be no apology for taxpayers, parents, teachers, employer groups and generations of Australians who have been let down by dodgy policymaking.

“My area of languages is a classic example. As people have known for millennia, learning another language … requires all of those traditional approaches like memorisation, mastery of grammar and spelling (which is so good for your first language, anyway) and increasingly thoughtful and sophisticated communication.

“In the 1990s, we teachers were advised that memorisation was very old-fashioned and that it was unfair to ask students to write more than a sentence or a paragraph at a time, whether in English or a foreign language. Textbooks became superficial and incoherent, with lots of pictures and short texts but few methodical, helpful explanations of how a language actually works … And guess what, Australian student enrolments in foreign languages are far below those of the high-performing countries where every student is expected to learn at least two languages right through to the end of school.”

Mueller says the same has happened in science, mathematics and history, where anti-intellectual approaches now dominate.

“English is among the saddest examples because expectations (especially in written English) have fallen so dramatically and we now have generations of teachers who never mastered grammar or spelling and have very little confidence in their own writing.”

Yet “not one university academic in charge of training teachers, not one bureaucrat advising ministers or administering schools and not one taxpayer-funded organisation responsible for Australian education research will lose their jobs because of policy failure that they have overseen”, Mueller says. “This explains why so many have lost confidence in Australian education,” she says.

“After 25 years of teaching in secondary schools and universities, and trying to make a difference in policy roles, I’m one of the completely disillusioned.”

She says those pockets of excellence among dedicated and competent teachers should be the norm.

Mueller left ACARA after two years in the job because it became very clear “that the significant problems with the first version of the Australian Curriculum, including its size, lack of clarity and the three-dimensional design, were not going to be addressed with any urgency and there seemed to be no appetite for objective, intellectually rigorous debate about improvements”.

Much of the problem, she says, is the adoption of faddish so-called 21st-century competencies. Learning soft, transferable skills has trumped gaining knowledge.

“This is completely at odds with the hard yakka of acquiring knowledge as we’ve done for centuries. Instead, policymakers have knowingly taken on shallow, unproven globalist fads that focus on collaboration, communication, creativity and critical thinking.

“How have we allowed these to take over from the systematic acquisition of knowledge?

“How do the proponents (of the current national curriculum) think every great civilisation has achieved so much, especially in the West?

“Incredibly powerful and enduring Western concepts of individual freedom, equality before the law, civic rights and responsibilities, the contest of ideas and respectful debate, trying to live one’s best life for the common good, all disappearing … not taught, not learnt, because poor education policies and poor curriculum mean young Australians don’t study history in any meaningful way, have no idea about the contest of ideas in a liberal democracy and won’t read anything that takes longer than a nanosecond and isn’t on a screen.”

Education reform hit a brick wall at the last review because the terms of reference ensured the same people responsible for our declining education system over decades would control the rejigged curriculum.

Academics teaching our teachers are not, says Mueller, a reliable source of advice. “They should be doing the research. They should be across all of the problems and the challenges of classroom practice and school leadership. They should be the go-to people, but they’re not.

“We’ve had generations of teachers going through teacher education programs (at universities) designed by people with variable ideological commitments, if I can put it that way.”

There is almost zero accountability from universities and academics preparing teachers for the classroom.

“It’s all about accountability. That’s it. That is the beginning and the end of it. Accountability for taxpayers, for parents, for employer groups, above all, for the young Australians for whom education is a lifetime investment.”

Mueller fears that we have lost generations of young Australians because those in charge of education lost sight of the standards and practices needed for a truly world-class education to produce the highest quality school-leavers.

Mueller hopes that Clare will consult a wider group of education experts and go straight to the chalkface. That means consulting teachers and principals shut out last time. “Each time there’s been a review, and particularly in the last review, teachers had to wait to be invited to be part of it. It was a closed shop.”

The national curriculum was introduced in 2008 by Julia Gillard to ensure equity across the country so that students moving between states or territories would be guaranteed a consistent world-class national curriculum.

The solution was worse than the problem: a consistently poor national curriculum. No wonder states such as NSW are going their own way.

If he has the intellect, determination and conviction for genuine education reform, Clare might achieve something that successive Liberal education ministers failed to do.