Have we elevated the choice to die on the clock over the choice to live and let nature decide?

Despite my dad’s significant pain, his loss of independence and deteriorating mind, he never stopped wanting to be here.

It will be six years next month since my dad left us.

Left us. Such strange words we use around death. Those words make it sound as if he were going on a holiday. Or back to Italy to live.

I’ll never forget that morning. A bright, crisp early winter’s Saturday in Perth. A clear, deep blue sky emerged from dawn. I’d left the hospital just after midnight.

“Your dad has at least a couple of days left, possibly three,” they told me. “Go home tonight, sleep in your own bed, and tomorrow, we’ll make you up a cot and you can stay here.”

It seemed reasonable but Bruno was not a reasonable man, and when it came to doing what he wanted, when he wanted, he was not for turning.

So, I covered him with my scarf, kissed his forehead and told him I’d be back around 8am with coffee and the papers.

It was around 6.30 the next morning, just as I’d dragged myself out of bed, when my brother phoned. “He’s gone.”

Two days my arse – I could hear Dad laughing at us the way he used to when he felt he had the upper hand, which was a lot.

It’s not that I don’t think about those moments any more, I do. They waft in and out of my mind and heart like smoke haze from a distant burn-off. With the passing of time the sting becomes less sharp and the ache less fierce. And more often than not these days I find myself reliving these scenes via a different context, through a different lens. Like when news broke this week that Carlton AFL legend Robert Walls had chosen to end his life, rather than endure another round of chemotherapy in his fight against a rare blood cancer.

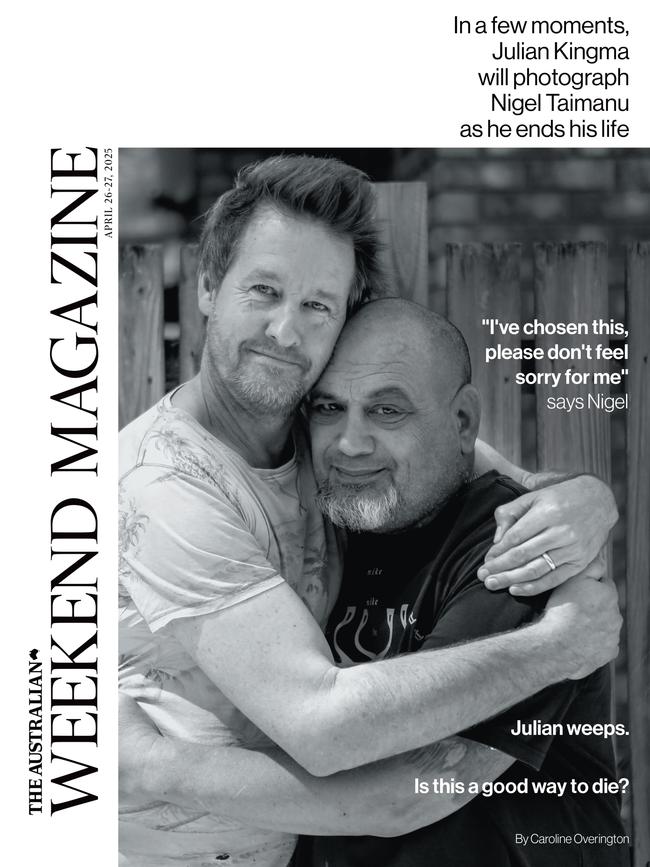

One such moment arose recently when reading Caroline Overington’s magnificent profile on photographer Julian Kingma in The Australian Weekend Magazine (April 26-27). Kingma, a renowned Australian portrait photographer, had embarked on a 12-month project in which he documented terminally ill men and women contemplating voluntary assisted dying to end their lives.

I wept as I read it. I don’t understand how anyone couldn’t, to be honest. It was raw and real and incredibly confronting.

It reminded me of our own journey as a family, but more than that. Reading about the choices these men and women were making reminded me of how fiercely and defiantly Bruno wanted to live. Live long enough to see his grandkids grow up and get married. See me get married again. (Sorry, Dad, bit of a failure there so far.) Despite his significant pain, his loss of independence and deteriorating mind, he never stopped wanting to be here.

As I read the stories, I couldn’t help but notice a theme, one that gently spoke of reluctance, even once the choice was made.

The first man we met, Nigel Taimanu, told Kingma “I don’t want to do this” but said he felt that cancer had left him no choice.

My dad wasn’t afraid to die. He was afraid to die in pain, and believe me when I tell you his pain was debilitating and constant.

In the end he had the good fortune to die in Perth’s largest teaching hospital, where excellent palliative care meant he didn’t suffer. As I read about Kingma’s work, I wondered if we are failing somewhat. Are we venerating, elevating, this pathway of euthanasia? Are we glorying in this idea of choice?

As we have embraced and normalised the practice of letting people take their own lives whenever they choose, have we concurrently dismissed those who wish to keep living despite their pain? Have we elevated the choice to die on the clock over the choice to live and let nature decide?

It’s a reasonable question to ask when you look at the data and at what Palliative Care Australia describes as a “postcode lottery”. If you need palliative care, whether you can access it will depend entirely on where you live, and that’s even before you factor in the terrifying lack of resources in regional Australia. As with most things, the bush misses out because policy typically is formed by people who never leave the city. And, as PCA chief executive Camilla Rowland told me this week, most patients in Australia who need palliative care and want it as their end-of-life pathway are receiving it only in the last 15 days of their lives.

“That’s not based on clinical care models or best practice, it’s based on budget restrictions,” Rowland said. How can that be?

We know that each year, of 190,000 Australians who die from predictable causes, only 70,000 or so can access specialist palliative care. The number of people aged over 85 will triple between 2022 and 2032 – what of this?

If you want VAD you can get it, obviously within the right medical context. From what I have read, any issue with access is related to doctors willing to engage. Though the Australian Medical Association recently released a discussion paper that canvassed the funding issue for VAD, including the sensitive topic of doctors charging or not for their role in the VAD process. It also advocated for doctors to be able to provide their services for euthanasia over the phone via telehealth.

Already, we know about two-thirds of Australians can’t access palliative care. How are we affording dignity in death only to those who mark the date on a calendar? What about people who, like my own father, wanted to eke out every last moment. Drink life to the lees? Stare death in the face and hang on until his body decided it was time?

Gemmy, I really don’t understand what’s happening here: his words were slurred. It was 48 hours before he died. Rest, Dad, I’d told him. Just rest and focus on getting better. Ahh, the lies we tell to comfort ourselves.

What I’m interrogating here is not based on any moral judgment of euthanasia. It’s my view that people’s opinion on this delicate subject is formed by ideology or, more commonly, suffering and loss or fear of it. My own position was formed in a similar melting pot and, perhaps surprisingly, completely free of any consideration stemming from my faith.

These are sacred, deep conversations. I understand why people choose VAD do so. I couldn’t but I understand why they do, and I can’t imagine what it takes to make that choice with a clear mind and go through with it.

But we simply can’t have a conversation, an honest one, about end of life in this country while one pathway is ignored and underfunded. Where access to palliative care is a situational lottery. Everyone talks about individual choice. It is a false narrative when there’s only one real option. What choice is there for those who wish to ride the wave to the end, rather than circle a date on the calendar? Must they suffer?

A 2020 research paper prepared by KPMG, Investing to Save: The Economics of Increased Investment in Palliative Care in Australia, outlined the strong economic argument for increased resourcing. There are many and they’re not especially complex. The paper demonstrates how reform and adequate resourcing will not only achieve better social and moral outcomes but reduce the annual $8bn bill that taxpayers foot around death and dying in Australia.

I remember so clearly, the wonderful palliative care doctor who stood with my brother, walking us carefully through the options. I guess we were lucky; is that even the right word? We had had the hard conversations ahead of time, so we knew what Dad wanted. I watched as she took a pen and went down what seemed to be an endless list of medications, striking them off the list. She smiled at us. “We’re going to make sure Dad’s comfortable and let’s just see what Mother Nature does,” she said.

I should have told her: Mother Nature might want to check in with Bruno. He did it when he was ready. Like he always did.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout