World waits for Harper Lee’s tale of the real-life crime that shook Alabama

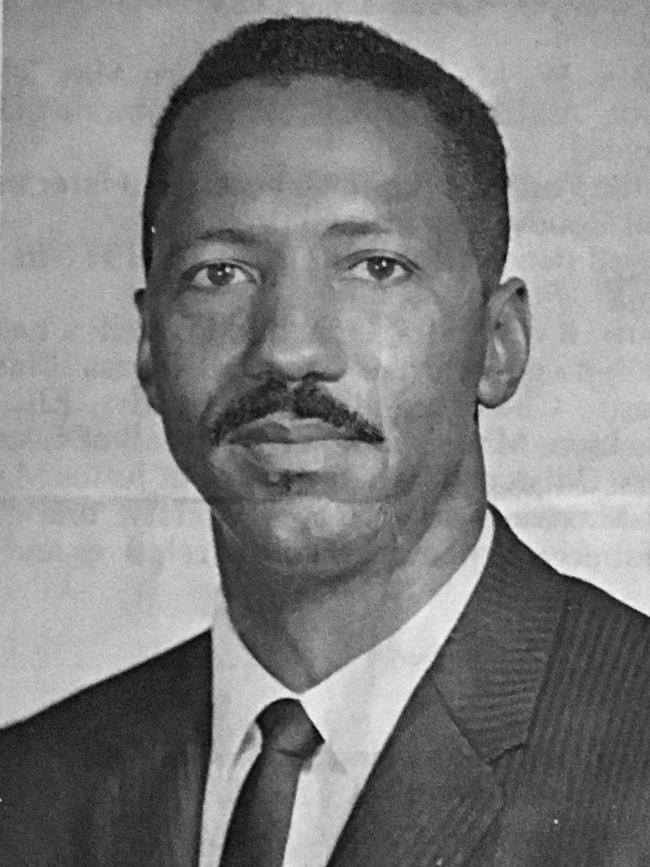

Reverend Willie Maxwell got away with murder again and again. Locals were convinced that voodoo spirits protected the obviously guilty serial killer.

In the rural-poor county of Coosa at the heart of Alabama is the small Peace and Goodwill Cemetery. The burial ground lies outside the backroads town of Rockford, which at the last census was called home by only 349 people – one in five of whom lives in poverty.

The graveyard was established in 1868 on land donated by a former slave, the Reverend Jacob Moore. A plaque at the gate notes many of the district’s local families buried there: the Drakes, Goggans, Leonards, McKinneys and Royals.

No mention, though, of the Maxwells.

For a time from the early 1970s the Maxwell family started filling graves there with almost indecent haste. Mary Lou Maxwell was buried there in August 1970. Dorcas Maxwell was buried there in September 1972. They were both wives of apparently luckless backwoods preacher Willie Junior Maxwell. Interestingly, they are at opposite ends of the cemetery.

Also there are the earthly remains of John Columbus Maxwell, Willie’s brother, who was laid to rest 18 months after his sister-in-law Mary Lou and seven months before her replacement. James Hicks, a nephew of Willie, also is buried at Peace and Goodwill. He was found dead next to his car in February 1976 not far from Willie’s home. The coroner could find no cause of death.

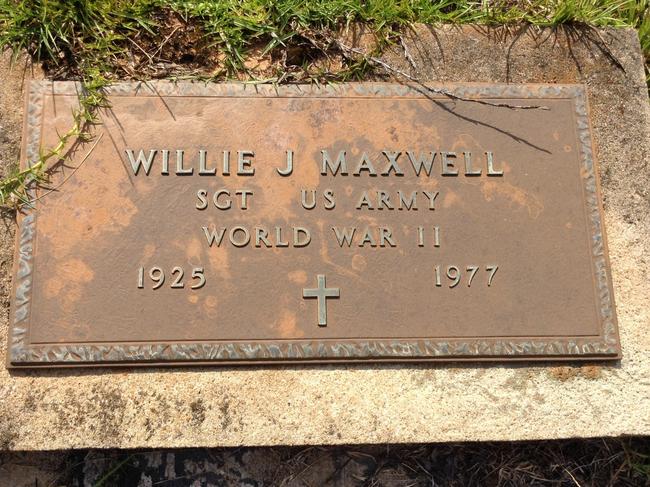

What binds them, other than blood and marriage, are numerous mail-order life insurance policies taken out on all of them by Willie, sometimes four for each victim. He too is spending eternity beneath the scrappy lawns of Peace and Goodwill, where he was buried in June 1977 and on whose headstone is written “Willie J. Maxwell Sgt World War II”.

That’s true, but there’s a bit more to his story. Willie was shot dead the week before at the funeral of his stepdaughter Shirley Ann Ellington. The always immaculately dressed, Bible-quoting minister had taken out life insurance policies on her behalf too, of which he was the sole beneficiary.

Someone else draws all these lives together: John Thomas “Tom” Radney, a white Alabama lawyer and one-time Democrat senator who was happy to represent black clients. It was Radney who acted as Willie’s lawyer and chased down the numerous insurance policies Willie had signed up for ill-fated family members.

Perhaps Radney believed Willie’s life was blighted by these cruel coincidences; he aggressively sought each payout, often taking the insurance firms to court – and winning every time. He reportedly received commissions on the paid-out policies.

The reluctance of these insurers was understandable. Each of the deaths was a crudely staged and covered-up murder. The killer was Willie Maxwell. But it was an era when police often chose not to concern themselves with family disputes, even if they involved violence. And it was common then also for police to be less motivated by black on black crime.

Willie got away with murder again and again. So much so that locals were convinced he practised voodoo rituals and that the voodoo spirits protected the obviously guilty serial killer. Some even spoke of how he could transform himself into a black cat. The law was never able to catch up with Willie but justice did.

Saturday, June 18, 1977, was clammy hot across Alabama as 300 people gathered for the committal of 16-year-old Shirley Ann at the nearby one-room House of Hutchinson Funeral Home in Alexander City just outside Coosa County. She had been killed the Saturday before. At first it appeared that she had had a flat tyre while driving Willie’s borrowed car on a secluded road not far from his home. It seemed that she had stopped to change the wheel, had jacked up the front of her vehicle, which slipped from the support and crushed her skull.

Shirley Ann had been eligible to drive for just six months. It was quite possible she had never encountered a flat tyre. It is likely she would have been changing a wheel alone for the first time. But despite the dry dirt roads and handling the dusty tyre, Shirley Ann’s hands and fingernails were spotless. Oddly, neither were any of the tyres flat.

The preliminary post mortem indicated a ligature had been placed around her neck and that she had been strangled before the accident. Also, although investigators did not know this at the time, Willie had taken out a life insurance policy on the girl so recently he had not yet paid the first instalment.

A funeral director handed out paper fans for the sweaty congregation gathered in mourning that day for the loss of such a young life. As is common in Alabama, it was an open casket. At the conclusion of the service, those who knew or were related to Shirley Ann slowly walked past the coffin with its raised lid. One of them was Willie’s third wife Ophelia (nee Burns, with whom he had had an affair while married to Mary Lou), who gasped and appeared to be on the verge of unconsciousness when Willie grabbed her and returned her to the third row of pews.

Next up was Shirley Ann’s older sister, Louvinia Lee, who viewed the body, then turned and pointed at Willie, shouting: “You killed my sister and now you gonna pay for it.” With that Louvinia Lee’s uncle, Robert Burns, dressed prominently in a green suit, stood up in the pew behind Willie and aimed his .25 calibre Beretta – the James Bond model – from point-blank range and shot him three times in the head.

Burns then dropped the gun and waited for police directing traffic out the front of the church to enter and arrest him. As patrons fled for the exits, two officers approached Burns, who admitted to them he had killed Willie. “I had to do it,” he is recorded as telling them, adding that he’d do it again.

The events that unfolded over the next few days were like a plot from a southern gothic novel: Radney, Willie Maxwell’s long-time lawyer, sensationally volunteered to represent killer Burns, vowing to get him off the murder charge and setting the scene for a fabled court case that pitted family against family and involved six violent deaths.

Reading reports of these events in The New York Times over breakfast in her unremarkable Manhattan apartment was Harper Lee, whose legendary first novel, To Kill a Mockingbird, had won a Pulitzer prize and sold more than 40 million copies. Lee’s book looked into the dark heart of the American south, its injustice, poverty and racism.

Here was an equally macabre set of events that spoke of the same issues and whose central character is shot dead. In Mockingbird, Tom Robinson, an innocent man, is killed; in Alexander City many innocents were killed until the guilty Willie was delivered his own rough justice.

The parallels and contrasts with Mockingbird are irresistible and Lee was drawn to them.

One of the characters in Mockingbird is Dill, based on the real childhood friend Lee made in Monroeville in southern Alabama. Dill essentially was Truman Capote and the pair remained friends as their literary careers bloomed. About the time Capote finished his novella Breakfast at Tiffany’s, which was being made into the famous film, Lee’s first novel – there would be only one other and that in contentious circumstances – was topping The New York Times’ bestseller list.

By then, Capote had set out to tell the tale of the murders of the Clutter family in mid-west crossroads town of Holcomb in west Kansas in December 1959. Farmer Herb Clutter, his wife Bonnie and their children Nancy, 16, and Kenyon, 15, were bound, gagged and shot dead in different rooms of their home by newly released prisoners Richard Hickock and Perry Smith. Two of life’s perennial losers, they decided to steal a safe they were told Clutter kept loaded with cash. There was no safe and they escaped with $40, a pair of binoculars and Kenyon’s transistor radio.

The Clutters’ were the most infamous killings in the US until the Manson murders a decade on.

The killers were caught in Las Vegas six weeks later, by which time Capote and his friend Lee were already in Holcomb interviewing the locals – Capote would go on to interview and befriend Smith on death row – for what would become his acclaimed and groundbreaking “nonfiction novel” In Cold Blood.

Capote wrote 8000 pages of notes in preparation for the book – many hundreds of them with the assistance of Lee – which was published in January 1966, nine months after the Clutter killers were hanged.

Without Lee by his side, it is unlikely In Cold Blood would have made it to the printers. Holcomb locals thought the pudgy, overanxious Capote with his squeaky voice, thick-rimmed spectacles, cardigans and Panama hat was weird, like some sort of escaped neurotic and pushy hobbit. But the rural common sense of Lee, always at his side, won them over.

Capote had Lee’s name prominent in the list of acknowledgments in the first draft for In Cold Blood but later struck it out. It was known that he was envious of her international success with Mockingbird and of the big-budget Hollywood film of starring Gregory Peck that was under way.

Capote went on to become a bitchy, often newsworthy celebrity fixture on Manhattan where he spent drunken lunchtimes with his circle of “Swans” – wealthy New York female friends for whom he was an amusing, gossiping lapdog.

Once they had told him too much, he betrayed them in an essay for Esquire titled La Cote Basque 1965, based on the name of the restaurant at which they gathered daily. He revealed their secrets in an act of social suicide from which he would never recover.

Lee largely kept to herself while neighbours and journalists kept their distance – her last two interviews were in 1964 and 1978. She was friendly enough, it was just that she did not want to be asked about her life or her famous book.

Her spartan one-bedroom flat with its book-lined lounge room was on East 85th Street. Her name was on its list of residents as Lee H, but no one is known to have pressed the buzzer. Once, when a neighbour’s teenagers held a party, she complained about the noise and said if they didn’t quieten down “I will buy the building and evict you”. She travelled back and forth to Monroeville and would pop into literary festivals while publishing agents wondered if she would ever write again. Her dependence on alcohol deepened and friends reportedly spoke of late-night rants.

The world had long awaited another book from Lee. Mockingbird had been on school syllabuses for years and the masterful film starring Peck had been seen by many more millions while picking up all the major Golden Globe awards and being nominated for eight Academy awards, winning three including best actor (Peck) and best adapted screenplay.

Finally, the trial for the murder of Willie Maxwell proved irresistible to the former law student Lee who had always been fascinated by serious crime. She moved to Alabama, before Burns’s trial began, and interviewed relatives of the dead and living, local police, lawyers and shopkeepers, and pored over post-mortem reports and marriage licences. Among those to whom she spoke was Radney and the pair became quite close. Radney had visions of a bestseller book and, inevitably, a Mockingbird-big film, and even wondered who might play him. Lee had mentioned Peck.

The district attorney’s case against Burns looked obvious and as uncomplicated as murder could be. The DA said the killer had “acted as a one-man lynch mob”. Radney’s first words to the jury were: “We admit he killed him.”

But he argued during the brief trial that Burns, who’d served in Vietnam where a cousin had been killed and who had witnessed many comrades die, suffered a nervous reaction to it all. (PTSD would not be named until 1980, but its symptoms had long been diagnosed and understood.) Radney argued that Burns’s actions had been impulsive – he had been momentarily overwhelmed by his psychosis – and he had not been responsible for them.

The jury considered its verdict for five hours and returned a not-guilty verdict. The courtroom, filled with family of the murdered Maxwell clan, rose as one in applause. Lee, almost anonymously, was also there.

She stayed in town for weeks after, long enough to see Burns released from a mental health facility and return to driving trucks. She spoke to him at length and returned to Alexander throughout 1978 to talk to him more and take notes. Once, when Radney asked about the progress of her book on the case, Lee sent him a few scene-setting pages on top of which she had scrawled “The Reverend”, presumably the title she had in mind for the book. But it never came.

From time to time, reporters and literary agents would ask Lee’s legal counsel and minder, her sister Alice, if she knew anything about The Reverend. Alice died aged 103 in 2014. She had still been practising as a lawyer when aged 100. She would say the manuscript had been accidentally burned, or the notes and files lost, and sections had been misplaced in the move back to Manhattan.

The following year, it was unexpectedly announced that a sequel to Mockingbird would be published. Go Set a Watchman was published on July 14, 2015. Essentially, it was the first draft for Mockingbird that book editor Tay Hohoff in 1957 had encouraged Lee to rework into Mockingbird.

Many of the characters and some of the chapters were clearly the same. Some thought Lee might have been coerced into allowing it to be published, but she made clear that was not the case. The reception for Watchman was lukewarm and the flaws Hohoff had warned against almost 60 years earlier were obvious.

Lee died in 2016 and that seemed to be the end for The Reverend. But news of Lee’s “new” book, had piqued the interest of a writer for The New Yorker, Casey Cep, who followed Lee’s path around Alabama, retraced her life in Monroeville and Manhattan, and cleverly brought the strands together in the well-received Furious Hours: Murder, Fraud, and the Last Trial of Harper Lee. (Furious Hours was not well-received by The Australian’s Gideon Haigh, who wrote at the time that “Cep seems so in awe of the various writerly reputations that she misses what seem fairly obvious conclusions: that the Maxwell story is rather less than the sum of its parts.”)

When HarperCollins announced in March that it was publishing eight short stories by Lee – the collection, The Land of Sweet Forever: Stories and Essays, will be out in October – there was excitement internationally that this would include her work on The Reverend. But the short stories, found last year in files reclaimed from her Manhattan apartment, are of drafts and stories that predate Mockingbird.

The upcoming stories have been approved by controversial Monroeville lawyer Tonja Carter, who has looked after Lee’s legal affairs in life and ferociously guards her legacy in death.

It was Carter who won approval for Watchman, the manuscript for which she said she found overlooked in one of Lee’s safety deposit boxes. She said at the time that she had also found the manuscript for a third novel. Certainly, we know Lee had used real names and some pseudonyms for the first pages of The Reverend sent to Radney which, as with In Cold Blood, was planned to be a nonfiction novel.

Asked about the Watchman find in 2015, Carter told The Wall Street Journal: “Something else was in the … box. The manuscript for Watchman was underneath a stack of a significant number of pages of another typed text.”

Watchman sold 1.1 million copies in its first week and in all formats has sold millions more. Signed copies sell for more than $8000.

If it is complete, The Reverend will sell millions more telling a depraved story never heard during the Reverend Willie Maxwell’s time on earth of a uniquely wicked life lived in plain view.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout