Anthony Albanese rolls out his election battle plan

As parliament finishes for the year and the focus shifts to the 2025 election, the big questions are: Can Albanese win? And can he lose? The answer to both questions is undoubtedly and obviously: Yes.

The Prime Minister’s plan is built on the basis of his victory against Scott Morrison and seeks to exploit the weakness of the conservative side during the 2022 election and the current weaknesses of his opponents on the left.

Albanese’s narrow first win was a result of three factors: Morrison’s unpopularity; the Climate 200 independent teals’ sweeping defeat of sitting Liberal MPs in their heartland; and a surge of popular vote in Western Australia.

At the next election Albanese intends to try to replicate those winning conditions by demonising Peter Dutton so those wealthy teal seats are likelier to vote against the Liberals; concentrating on WA to hold Labor’s lead; and adding a defeat for Greens MPs in former Labor seats in inner-city areas as an insurance policy to bolster his bare majority.

Albanese hopes he can win as many as four Greens seats back for Labor, and at least two, which will enlarge his majority if he doesn’t lose elsewhere.

But there are substantial risks in adopting a strategy with inherent contradictions, the potential to turn away Labor supporters and a seemingly dubious belief that the Opposition Leader is unelectable.

Having committed wholeheartedly to this strategy, and totally convinced of success, Albanese and Labor have no choice but to pursue the plan because they seem incapable of creating a reset in politics. What’s more, the circumstances for Albanese at the end of this term are vastly different to the start of his term when he had a long-lasting honeymoon with business, the media and voters.

All the polling shows the ALP primary vote is stuck at, or below, the election level of 32 per cent. The Coalition is now in front on a two-party-preferred basis, Dutton is closing on Albanese as preferred prime minister, and Albanese’s voter satisfaction rating is falling.

Labor also lags well behind the Coalition on all the key issues from economic management to easing the cost of living. Labor’s economic promise has dulled and Dutton’s constant query to voters – “Are you better off now than you were three years ago?” – is cutting through.

As a result, as parliament finishes for the year and the focus shifts to the 2025 election, the big questions are: Can Albanese win? And can he lose?

The answer to both questions is undoubtedly and obviously: Yes.

Yet the permutations are more complicated than a simple yes or no with the consideration of whether Labor can be elected with an outright majority or will, like Julia Gillard, be reduced to a minority government dependent on independents and/or Greens.

Any assumptions at this stage about the outcome of an election in March or May next year – even the now almost universally accepted wisdom that Labor will slip into a minority government – need to be treated sceptically.

So, too, does any blind belief that first-term governments do not lose or at least have not lost since 1931. Given first-term governments since World War II have all lost ground at their second election and the Albanese Labor government was elected with the lowest primary vote and narrowest margin of all of them, it is the immutable arithmetic of seats – not the irrational assumption of some collective public sympathy – that will decide whether Albanese becomes the first leader in almost a century to be defeated at the first attempt at re-election or the first in two decades to be elected at successive elections.

The key complementary question to “can Albanese win?” is: Can Peter Dutton win?

Again, the answer is yes but, less emphatically because he has the bigger challenge and there need to be signs of an even bigger swing to Dutton and the Coalition than are now apparent.

At his first caucus meeting after the election in 2022 the Prime Minister started to talk football-style about “back-to-back premierships”, and this week, at his last partyroom meeting of the year, he talked about leaving “nothing on the field” with the aim of getting an outright victory next year.

Albanese has a re-election plan aimed at a returned majority Labor government that involves US-style rallies; a focus on the benefits his government has delivered on wages, childcare, medicine and taxes; a relentless attack on Dutton; and an almost counterintuitive fight with the Greens on the left.

In the first answer of his last question time this year Albanese rolled out his streamlined list of achievements as he simultaneously forced through what legislation he could in the Senate and dumped what he couldn’t.

Albanese said: “Over the last fortnight of the parliament, we have concentrated on major reforms that will make a real difference for people: legislation to provide cost-of-living relief including helping 40,000 Australians buy a home, free TAFE, fixing student loan indexation, increasing wages for early childhood workers.

“The Senate is expecting to pass more than 30 pieces of legislation … making a real difference, building more rental properties to take pressure off renters, protecting consumers purchasing buy now, pay later products, strengthening Australia’s protections against money laundering, strengthening and modernising the Reserve Bank of Australia.

“We are getting things done, they are just getting angry. We are acting responsibly, they are acting recklessly. We are cutting the cost of living, they are cutting Medicare pensions and housing, that’s what they want to do,” he said as he rehearsed the election campaign.

On Friday, Dutton described Albanese’s clearing of the decks and dumping of legislation he couldn’t pass as a “going-out-of-business sale. It was like just everything discounted and whatever it takes to clear the shelves.”

But there was more to Albanese’s flood of late legislation and barnacle clearing than just depicting Dutton as angry, arrogant and reckless as part of a personal attack. Labor was simultaneously hitting the Greens.

After months of attacking the Greens for their radical position on Palestinians and Israel and then accusing the Greens of joining Dutton to block Labor’s housing initiatives designed to create more housing stock for lower-income buyers and renters, Albanese refused to do a deal with the minor party and stared them down on a raft of proposed legislation.

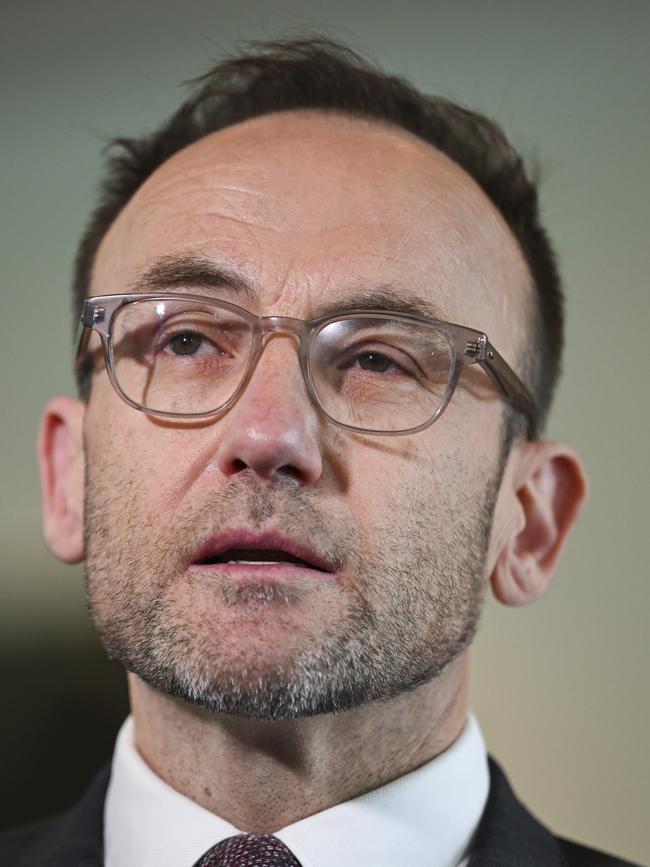

After years of fighting Greens with as much vigour as fighting tories, Albanese decided to tough it out with Australian Greens leader Adam Bandt and assume – correctly – that the minor party would prefer to side with Labor than the Coalition and would cave in.

This is precisely what happened in the last rush of bills in the Senate as the Greens agreed to pass legislation en masse and Labor got almost 30 bills through at one go.

The Prime Minister got his Greens cake and ate it too – he was able to boast about getting his agenda through and denied Bandt the electoral boost of claiming a victory with any meaningful compromise. But this is where some of the risks lurk for Labor.

Although the Greens have gone backwards in elections at all levels in Queensland, NSW, the Northern Territory and even the bastion of woke – Canberra’s ACT – there is still strong support for the Greens among younger voters Labor is trying desperately to hold on to with various giveaways including forgiving student debt.

At the other end, Albanese ultimately using the Greens vote to pass an avalanche of laws creates a foreboding among older voters, who do not believe he won’t do a deal with the Greens to form a minority government if he has no choice.

Indeed, after Bandt was forced to vote with Labor on the Help to Buy and Rent to Build housing schemes after months of infighting there was a chilling warning that will not have helped Albanese’s campaign to say he will not form a coalition with the Greens if he loses majority.

Bandt said: “There comes a point where you’ve pushed as far as you can. We tried hard to get Labor to shift on soaring rents and negative gearing, but we couldn’t get there this time.

“We’ll wave the housing bills through and take the fight to the next election, where we’ll keep Peter Dutton out and then push Labor to act on unlimited rent rises and tax handouts to wealthy property investors.”

Albanese may fulminate as much as he likes and give his word as his bond as many times as he likes, there’s no one who believes the Greens will not direct policy for a Labor minority government.

This was even more apparent with the upending of a deal between Tanya Plibersek and the Greens over the “nature positive” legislation and the creation of an environmental protection authority that involved further developments after the next election.

The mining industry saw this as a direct threat, the Greens saw it as a win and the Environment Minister wanted the laws passed, but Albanese saw the double trouble of giving the Greens a win and antagonising the resources-rich state of Western Australia, which is the key to his remaining in power.

WA Premier Roger Cook has developed into a fifth wheel in the Albanese cabinet, not just sitting in three times but actually changing the direction of the cabinet decision to be in Western Australia’s and the mining industry’s favour.

This was a case in which Albanese didn’t want to give the Greens a win and didn’t want to antagonise Western Australia.

There was even a role for the Labor Senate “rat” Fatima Payman, who could see the opportunity to boost her now independent profile in Perth if she rattled Labor’s cage on mining.

That the environmental wing of the ALP was outraged seemed not to bother the Prime Minister, who could see the dumping of the environmental watchdog – an election promise – served the triple purpose of heading off Dutton’s pro-mining push, frustrating the Greens and helping Cook.

There is likely to be one of Labor’s US-style campaign rallies in Perth as Albanese burnishes his WA credentials and spends as much time in the west as he can.

It’s a plan based on past form but rests heavily on Labor not losing seats elsewhere, winning Greens seats, the Liberals not winning teal, Greens or Labor seats, and dissatisfaction with Labor not tipping into a big swing to the Coalition.

Analysis by electoral expert and emeritus professor Murray Goot demonstrates that first-term governments have not lost since 1931, Labor as a result of the Depression, not because of the size of the swings against them but the size of the margins with which they were elected. “Governments fail to fall at the end of their first term because of the margins by which they are elected in the first place,” Goot wrote not long after the 2022 election.

Despite big swings against the Howard, Gillard-Rudd, and Abbott-Turnbull governments, it was the even bigger winning margins of John Howard, Kevin Rudd and Tony Abbott that saved those first-term governments from defeat.

Goot points to the Labor governments elected in 1972 and 2007 being buffeted by global economic shocks and asked: “Will economic circumstances come to the aid of the non-Labor parties again?” – especially since Albanese’s government has the lowest vote and thinnest seat margin of them all.

The three pillars of Anthony Albanese’s strategy for election to a second term next year became dramatically apparent in the last two weeks of parliament in 2024, in all its determination, political brutality, risk and desperation.