In the process, Albanese is making two ambitious calls – the test of success is winning majority government in 2025 and that “the worst is behind us” on the inflation front. He wants to discount acceptance of minority government, aware it is the halfway station to defeat, and he wants to sell growing optimism about the economy.

It is an obvious strategy and it is high risk.

It rests on two assumptions that could go wrong: that Albanese can engineer a political recovery from the current dismal polls that point to minority government; and that economic indicators before polling day will give credence to his message about an improving economy.

There is an unmentionable bottom line here: how long will Albanese survive as PM if these two assumptions cannot be realised? Have no doubt, Albanese is fighting for his political future and his reputation as PM. This vulnerability will drive much of Labor’s campaign and what will become a fierce assault on Peter Dutton’s character and policies.

Election 2025 will be heavy on the negatives. Anyone who doubts this should examine Labor’s rally in Adelaide at the weekend, featuring Albanese, deputy Richard Marles, Foreign Minister Penny Wong and the nation’s most charismatic premier, Peter Malinauskas. It reminds of the firepower Labor can assemble.

Albanese’s message was his government has loads of refuel capacity. He recycled his potent message from the last election – “no one held back and no one left behind”. On cost of living, he said we faced a global storm and “we have navigated it in the Australian way”. Yet selling such optimism demands evidence – Albanese needs a pre-election interest rate cut by the Reserve Bank to put credibility in his saddle bags.

He denigrated Dutton for his “stop it, block it, wreck it” mantra, alleged that under Dutton Medicare “will be lost forever”, claimed that voting for Dutton meant “a nuclear reactor in your backyard”, and that Dutton’s behaviour was “bullying”, “wrecking” and “heartless”.

Sounds familiar? Get ready for the politics of 2025. It will resemble a re-run of the negative campaign that knocked out Scott Morrison in 2022. Indeed, Albanese gives every sign of wanting to campaign on Morrison’s mistakes. Yet every election is different – Labor needs to beware thinking 2025 can be a repeat of 2022, because that rarely works.

At the same time, Albanese wants to define a second-term agenda. He told caucus on Tuesday there will be new policy releases in coming months. The immediate start was the announced 20 per cent reduction in all student loans to assist about three million people at a cost of $16bn. Those with an average student debt of $27,000 will see their debt reduced by $5500 and for someone on $70,000 income the saving in repayments is $1300.

This builds on the earlier change to the indexation formula that cost $3bn and the delivery of 500,000 fee-free TAFE places. The legislation won’t be introduced until after the election, ensuring it becomes a frontline issue with Labor pledging it will become the first bill pursued post-election. Labor has polished its lines. Jim Chalmers said while Labor “is the party of low student debt, the Coalition is that party of high student debt”.

It’s all part of a broader tactic. Albanese wants to change the debate about what the government is doing to the election policy contest: Labor versus Coalition. Labor believes the more the Coalition’s policies are assessed against Labor, the more the polls will turn Labor’s way. Albanese needs this new politics – and needs it now.

One of Labor’s big election items will be advancing towards universal childcare. Indeed, this may become the centrepiece of Albanese’s 2025 campaign given the recent Productivity Commission report with the goal of creating “a high-quality universal early childhood education and care” system (ECEC).

The report wanted the childcare subsidy raised to 100 per cent of the hourly rate cap for families on an income up to $80,000 with a taper from this point. Half of all families would be eligible for subsidy rates of 90 per cent or more. The cost would increase to at least $17.4bn annually but the commission conceded the actual cost was likely to be above this. The aim is to provide 30 hours, or three days a week, of quality care for 48 weeks of the year.

Speaking as opposition leader, Albanese said: “Labor created Medicare – universal healthcare. We created the NDIS – universal support for disability. We created superannuation – universal retirements for workers. And, if I’m prime minister, I will make quality, affordable childcare universal too.”

This is Albanese’s vision. It is highly likely he will enshrine this at the heart of his 2025 campaign. It constitutes an entrenchment of the contemporary Labor philosophy – big, government-funded, ambitious agendas, universal in scope, free as much as possible, presented as a fusion of social and economic policy and geared to vote-winning. Above all, it vests Albanese with a historic achievement as PM.

It seems, however, that he may get more ambitious. There is pressure within government to overlook the PC recommendation and opt instead for a flat-fee model (with the PC assessing in its report a $10-a-day flat fee). The PC found this model involved “a much higher additional cost to taxpayers”, costing an extra $8.3bn a year, plus it involved a “disproportionate” share of public support going to the “top 25 per cent of the income distribution” – those on more than $160,000 in income, few of whom need such help.

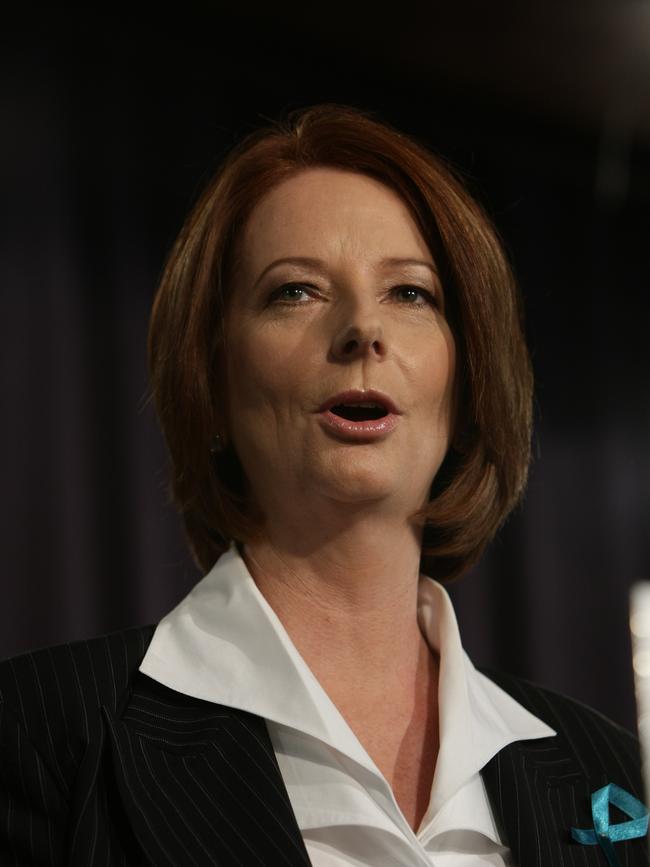

This is what happens when universalisation of benefits is pursued. For the record, ECEC spending by government increased by 40 per cent in real terms in the decade to 2022-23. But Labor seems hooked on these grand visions, almost regardless; witness the NDIS under Julia Gillard, a flawed program whose cost was hopelessly underestimated.

Both the $16bn student loan cut and any future childcare vision that will cost far beyond $17bn come when Australia has an inflation challenge, not yet resolved; when public spending is already at record highs; when the public sector is crowding out the private sector; when any childcare spending estimates risk being underdone; and when there are serious equity arguments against both schemes, as a conga line of economists along with the PC have highlighted.

Economist Chris Richardson said of the student loan decision: “It’s an election bribe. It fails the fairness test. It takes money from the less-well-off and gives it to the better-off.” Average student debt is less than 4 per cent of the extra after-tax income that they get from their study.

The student loan decision and a future childcare decision are motivated by politics – or Albanese’s future. Any childcare decision, moreover must be relentlessly assessed, since the PC has already said the labour market benefits are minor. These issues reveal much about Labor; its electoral strengths are the education sector and working women, and it seems willing to redistribute funds in their interest, even at the cost of the less-well-off.

There are four big questions. Do such big spending decisions undermine Labor’s economic credentials at the election? Probably yes. Do they undermine Labor’s fairness credentials? Probably yes. Do they show Labor’s identity is tied to universal big-spending agendas regardless of the economic situation? Probably yes. And will they work politically in an election campaign? Probably yes.

More Coverage

The bigger message identified by my colleague, David Penberthy, was how Labor ramped up its negative campaign with Marles in the lead

The bigger message identified by my colleague, David Penberthy, was how Labor ramped up its negative campaign with Marles in the lead

Anthony Albanese is throwing the switch to campaign mode. His focus is Labor’s agenda for the next term and his real purpose is to speed up the Labor-Coalition election contrast. Albanese wants to break out of the current political cycle that points to Labor’s decline.