It is, of course, true that the Greens have a long record of advocating lawlessness. Already in 2019, the party’s leader, Richard Di Natale, vaunted the Greens’ “strong and proud tradition” of breaking the law. Describing himself as the only Green parliamentarian who had “not yet” been arrested, Di Natale claimed it was entirely “appropriate” to breach “bad laws” – that is, laws with which the Greens, but not a democratically elected parliament, disagreed.

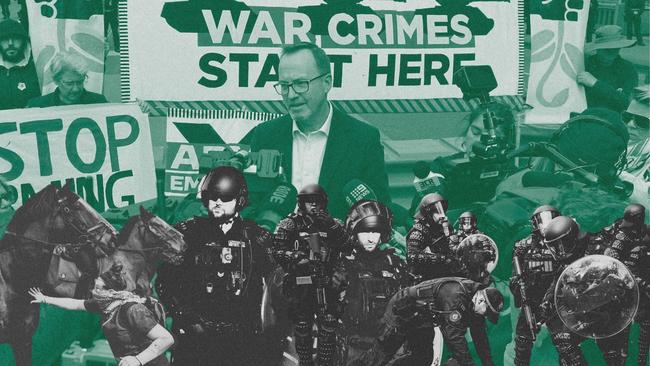

But even with that record behind them, excusing the violence that left 27 police officers injured has taken the Greens’ defence of illegality to new and dangerous heights.

At least originally, when their focus was on the environment, the Greens’ disdain for the law reflected a mindset dominated by premonitions of the end of days. Showing all the hallmarks of an apocalyptic eschatology – that is, a vision that combines a terrifying image of the last things with an announcement of their impending arrival – that mindset centred on the “climate catastrophe”.

The Greens were hardly alone in advancing climate-related prophecies of doom. Decades before Greta Thunberg burst on the scene, James Hansen had warned that there was a small, rapidly shrinking, window of time in which to prevent a “world-ending cataclysm”.

Echoing Hansen’s call, UK and Dutch prime ministers Tony Blair and Jan Peter Balkenende claimed in 2006 that without dramatic, globally co-ordinated action, a “catastrophic tipping point” would inevitably and irreversibly be crossed by 2023 at the very latest. And UN secretary-general Ban Ki Moon further shortened the time that remained to “save the planet”, saying in 2006 that it was only if global emissions had stopped growing by 2019 that “catastrophic consequences” could be avoided.

Given those visions of humanity quaking in the antechamber of its own extinction, it is hardly surprising that Bill McKibben urged protesters to do whatever they could to disrupt “business as usual”, so “we’ll at least be able to say we fought”. Democratic niceties, James Lovelock asserted, had to be “put on hold”, as protesters forced governments to impose on voters the immense sacrifices needed to avert “Gaia’s revenge”.

Nor is it surprising that anyone who dared question those propositions was denounced as a “climate denier”, implying, through the deliberate rhetorical proximity to “Holocaust denier”, not just normal fallibility but wilful error at its most morally abhorrent.

That descent from righteousness to self-righteousness, and from self-righteousness to the apology of violence, would have been chillingly familiar to those who know the history of apocalyptic movements.

As Norman Cohn showed in his landmark The Pursuit of the Millennium (1957), apocalyptic movements invariably involve the “phantasies found in paranoia”, including the “megalomaniac view of oneself as the elect, wholly good, abominably persecuted yet assured of ultimate triumph”, along with “the refusal to accept the ineluctable limitations of human existence, such as fallibility, intellectual or moral”.

It was “phantasies” of that ilk that prompted the great Protestant reformer Philip Melanchthon (1497-1560) to coin the modern term “fanatics” for the Anabaptists, who “think with their blood, not their brains”, elevating rage above reason.

But what made that collective paranoia especially dangerous, said Cohn, was its “attribution of gigantic and demonic powers to the adversary”. “The distraught saw God and the devil locked in battle for men’s souls”; if the children of light could not destroy the children of darkness, “the end of the world would surely follow”.

And more often than not, the children of darkness were “the supremely powerful, always stubborn, ever-deceitful Jews”.

Of course, the Greens jettisoned God long ago; but they could never do without Satan. The “climate catastrophe” had imbued them with a deeply Manichean view of the world, pitting absolute good against absolute evil. As they morphed from environmental activists into a coalition of wildly disparate groups – ranging from “Queers for Gaza” to virulently homophobic Islamists who would happily crucify any “queers” they could get their hands on – the Manicheanism, with its consuming need for a devil on whom to pin all sin, became even more intense.

That devil, wrote French psychoanalyst Ruben Rabinovitch in his study of mobs, “fulfils two crucial functions: it serves as the mob’s ‘negative’, on to whom its members project everything threatening, wicked and corrupt; and by shifting their focus from themselves on to a single “other”, it provides the cohesion without which the precarious coalition could not survive, much less become a movement”.

Or as Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt put it, the centrifugal tendencies inherent in the extreme politicisation of identity, which fragments the public into warring tribes, propels a “common-enemy politics” whose unifying basis is not shared hopes but shared hatreds. And the greater the capacity to whip those hatreds into uncontrollable fury, the stronger is the common bond.

That “common-enemy politics” has been on display for months. Indeed, the victims of October 7 had not yet been laid to rest before the Islamists and their fellow-travellers were on Sydney’s streets, yelling “where are the Jews?”.

That was merely a prelude to incidents that include a violent demonstration at a synagogue (triggered by Burgertory boss Hash Tayeh, who was involved in last week’s protests), an assault and kidnapping at a Jewish premise, the “cancelling” of Jewish speakers, and torrents of intimidation and abuse.

It is doubtful the situation would have degenerated as seriously as it has if governments and the police had acted more promptly and more forcefully. Instead, by appeasing the mob, they fanned the violence’s flames – and encouraged the Greens’ escalation of their uncivil war on Australia’s social fabric.

There is no prospect whatsoever of the Greens changing course. On the contrary, they are broadening their offensive, taking on the defence of the CFMEU’s thugs, extortionists and racketeers. As a result, the fundamental question must be whether Labor will reward the Greens – and their extreme views – by giving them its preferences.

In the end, that is a question of morality. And it is sadly true that political parties more readily sacrifice 99 per cent of their principles than 1 per cent of their votes.

But it is every bit as true that the symbiotic relationship between Labor as the host and the Greens as the parasite, which was once mutually beneficial, has mutated into one in which the parasite, sensing the host is in terminal decline, turns on the host, extracting as much as it can, as quickly as it can. Confident it can prosper despite the host’s demise, its change in strategy makes that demise all the quicker and more certain.

That is the trap Labor is now in. Whether it has the will, the skill and most of all, the moral courage to pull out of it is another matter entirely.

Historically, Australia’s major parties have never condoned the use of violence as a means of achieving political objectives. The Greens’ decision to whitewash last week’s anti-Israel riots in Melbourne therefore marks a grim moment in Australian political history.