Miranda July’s installation at Melbourne festival Rising might be her most surprising move yet

The filmmaker, artist and best-selling author is never one to resist a new thing, from her new art installation in Melbourne to changing the way women think about ageing and themselves.

Miranda July has been thinking about mini golf. Actually, she’d been thinking about mini golf before Melbourne festival Rising asked if she’d like to design a hole as part of a curation of artists tasked with reimagining the frankly surprisingly feminist origins of the game. (Circa 19th-century Scotland, women started their own version of the sport after getting fed up with their treatment from the male players.) The result will be an interactive experience, called Swingers: The Art of Mini Golf, taking over the Flinders Street Station ballroom until the end of August.

“Weirdly, right before I got asked, I had just gone mini golfing with my nephews and my brother,” says July. “So I literally had thought a lot about the design of them and how they’re kind of these weird little art pieces, but in this very colloquial accessible space. I was just like, ‘Oh, this is so funny that I’m being asked this. I actually have ideas.’” Her design will include July telling the player’s fortune.

A filmmaker, visual artist and writer, July likes trying something new. “I have a weakness for things I’ve just never done before,” she says. “And I’ve done a fair number of things.”

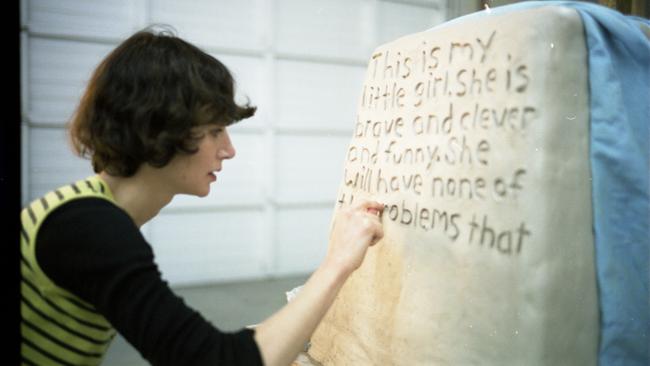

In March last year, a retrospective of her 30-year career doing many different things was held at Milan’s Fondazione Prada. Miranda July: New Society included new work such as F.A.M.I.L.Y (Falling Apart Meanwhile I Love You) (2024), a video installation made with seven strangers on Instagram, costumes and ephemera from her earlier performances, including the punk clubs she started out in, and a screening of her filmography, from 2005’s Me and You and Everyone We Know to short films and unreleased works. (Rising, together with ACMI, will also stage a mini Miranda July film festival, screening her films, shorts, documentaries, music videos and video art.)

Seeing so much of her work all at once in New Society, July didn’t react the way she thought she would. “I walked through it alone, kind of thinking I would just see all the things that were wrong with it. But I actually felt very moved and kind of a little sad,” she admits. “My heart kind of went out to this very young woman working so relentlessly hard and kind of like, ‘Why is she doing that? No one’s asking her to and the forms she’s working in are not going to be recognised,’” says July, with a laugh that comes easily and often, referring to her preference for performance art and installations. “I think, as a parent now, I had questions about what was driving her. And when I got to the second floor, which was more recent work, I kind of exhaled, like, ‘She’s going to be okay. These have a different energy to them. She’s all right, she’s taking care of herself.’”

In the past year, in fact since the exhibition opened, July has become enormously, culture-shiftingly recognised. Her book All Fours, about a 45-year-old ‘semi-famous’ artist and mother who decides to blow up her life, has transcended mere bestseller to become the kind of novel that has changed how people think.

Or perhaps how they talk to each other. There are All Fours book clubs where women in cities around the world meet to talk about the themes of the story, ones of desire and motherhood and ageing and chafing against the constrictions of the patriarchy and society and the ones we impose on ourselves. Sometimes these women send July photos from their catch-ups.

Much of her career has been about making connections and building communities, from her earliest days with Joanie 4 Jackie – a chain letter but with video tapes – to her email project We Think Alone (2013). In her films, including Me and You and Everyone We Know and Kajillionaire, characters often connect in unlikely ways.

“I really have spent a lot of my life trying laboriously to make communities,” she stresses. “I love to imagine women knowing that these other women in their community, not just me or these fictional characters or an audience, but literally their neighbours, like if the shit hits the fan, well, there is this group of women that you could maybe reach out to. That makes me very hopeful.”

Unlikely connections continue to delight her, such as her newfound friendship with our boy from Oz Hugh Jackman, who she reached out to after he posted a picture of All Fours on his Instagram feed. They now send each other long and discursive voice notes. “I really appreciated him posting about the book,” says July. “Not many men did post about All Fours and certainly not men as public as him. I love to think of all these Wolverine fans reading All Fours.”

Extremely long and incredibly detailed voice notes have become a new kind of enjoyable communication method among July and her friends. They call them podcasts. “They’re so, so comforting because sometimes it’s hard to find a time to talk, but to just do the dishes while listening to your friend have her half of the conversation, sometimes you get more of a complete meal with them just ruminating. I love that right now,” she says.

All Fours came after July, who recently turned 51, began grappling with her own mixed feelings about ageing. The book is not auto-fiction – something her work is sometimes assumed to be – but there are similarities between the unnamed protagonist and July. “I did think I’d be opening myself up for meanness, for ridicule,” she says. “That’s all I could really picture, but I thought if it succeeds the way I want it to then there will be this conversation with other women and that could see me through the end of my life. That conversation could keep going because I’m only going to get older and older, and that really might be worth it. And it is.”

Before her separation in 2022 and eventual divorce from her husband and the father of her child, filmmaker Mike Mills, July had started spending Wednesday nights in the studio she still works from, waking up to write on Thursday morning. “Every night really is Wednesday night now, because I live here [now] and it’s great,” she says. “I am so happy. I mean, truly not every woman’s divorce is like this. It’s what I wanted, and yet I feared that, even so, I would be sad and alone somehow. I couldn’t shake that fear.”

Unshackling herself from societal expectations – “You can do that?” other wives and mothers asked her – was not exactly the entire answer. “I’m discovering many of the ways I’m not free come from within,” she explains. “And that becomes clear once all or many of the external obstacles are gone. I would’ve just kept blaming this other person, who wasn’t helping, but it wasn’t all them.”

Still, she believes in reinvention, especially as we age. “I think, without a doubt, we not just reinvent, we transform,” she says. “Then, and again. I mean even if your mind is just calcified and you’re never going to change, and I do know some people like that, you age. You actually do keep changing, and the best I think is when those two things can be aligned, and the ageing can push your mind and spirit along.”

But the surprises of her own life are something she is trying to sit with for a bit. Including the changes that happened when All Fours ignited. A television adaptation is to come. “I don’t always feel like this, but I know if it was happening to a friend, I’d be like, ‘Maybe just relax, integrate that new feeling. You’ve done enough for now,’” she admits. “It’s been almost a year, but the truth is, it just kept on expanding. So there are a lot of things that are still quite surprising to me.”

That life has new seasons is something she is enjoying, too. Her child becoming a teenager and enjoying clothes in the way July always has is one of them. “I’ve been saving clothes for them – vintage clothes that I don’t want anymore, but that I think are really cool – in boxes for years,” she admits. “Just waiting for the moment when they might care. And that moment came and now we’ve entered this era of clothes sharing and getting dressed and it’s just very creamy and delicious.”

Is there anything she would tell that younger self from the exhibition who was so eager to put herself in the world? “Oh god, frankly, there’s nothing,” she says. “She’s not going to be stopped. She’s not going to slow down. There’s nothing you can say to her.” Only that perhaps it will all be all right in the end, and that other women will feel the same way.

Miranda July will be part of Swingers: The Art of Mini Golf at Rising 2025, Melbourne, June 4-15. Swingers will remain on display until August 31.

This story is from the June issue of Vogue Australia, on sale now.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout