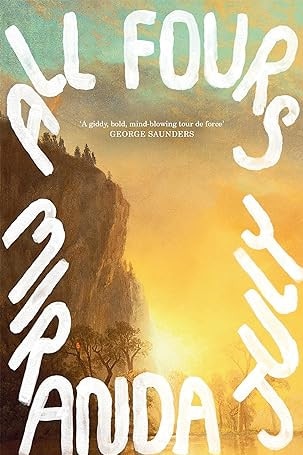

Miranda July’s All Fours: lust survives into middle age

This is a sexually explicit, radically honest look at a woman’s desires, into middle-age.

To say that All Fours is both strange and sexually explicit will come as a surprise to nobody familiar with Miranda July’s body of work across writing, film, and performance. Even so, All Fours is radical for its honesty about intimate relationships as July raises questions about boundaries: who has the power to impose them, and the extent to which they become internalised.

July’s first-person narrator leaves her child and husband and embarks on a driving holiday from Los Angeles to New York, where she intends to spend the week, but pulls off the road to refuel and becomes waylaid in suburban LA. Here she stays at a motel, in a room that she lavishly redecorates and becomes involved with a much younger man who works at Hertz.

July’s narrator is 45 and undergoing an apparent midlife crisis, which has to do with her feeling of a lack of agency in her own life. She observes: “Without a child I could dance across the sexism of my era, whereas becoming a mother shoved my face right down into it.”

Though the narrator’s husband is supportive and open-minded – their child is non-binary and their home-life accommodates both of their creative professions – the narrator’s actions indicate a feeling of being trapped. She tells us that most of her life had been spent in a state of “grit, grit, grit, then: release” and is recognising the limits of that pattern.

The revamped room, whose “tasteful opulence was shocking”, shows the narrator’s desire to have a space that is entirely her own, distinct from the home she moved into, owned by her husband. Her obsession with the younger man, who seems at first ordinary but whose secret talent is dance, represents an apparent yearning for her own youth.

For July, strangeness is often a route to authenticity. In her hands, awkward gestures become visible, the oddness of human interactions stripped bare. She tells us,

“Often I’m literally biting my tongue – holding it gently between my teeth – and counting to fifty.”

In an interaction with a pop star, the narrator observes the young woman pick her nose with her “dainty finger”. Everywhere and despite appearances, July seems to be saying, humans are idiosyncratic and these are actually points of true connection.

The narrator has memories of sleeping in a hotel bed next to her parents and hearing them have sex before she was asleep. Her father instilled in her the notion of a “death field”, infecting her with a rigorous fear of loss from a very young age. Her parents over-shared details about their relationship and it becomes clearer that the narrator’s own youth was prematurely lost to her.

There is another strand to All Fours, that has to do with women in midlife, dealing with the radical changes that befall a woman’s body as she approaches middle age. The narrator is concerned that because her hormones are about to “fall off a cliff”, she has a limited time remaining in which to take advantage of her libido. July’s narrator is possessed by the idea that, “at the height of our ascent we were middle-aged and then we fall for the rest of our lives, the whole second half.”

For women in particular, the second half of life seems to be determined by the choices made in the first half.

It’s an apt description for the book itself – July creates a very messy set of circumstances in the first half of All Fours and in the second half, sets herself the task of picking up the scattered pieces. The narrator seeks both freedom and the stability of marriage, but is “forever trying to avoid both entrapment and abandonment.” July is railing here against the binary structure of marriage – pointing out that intimacy and desire don’t fit neatly together. There is a lot of gnarly sex depicted in All Fours as the title suggests: both of the strange variety, and the deeply erotic.

Intimacy, July suggests, can be found in all sorts of relationships. It is in her closest friendship with Jordi, for example, that the narrator can be most honest about her feelings and desires. It is to Jordi she discloses that she is the “initiator” of her encounters with her husband, but “only because I’m trying to get out ahead of the pressure”. With her husband, the narrator is much more guarded, because her honesty has immediate consequences for her day-to-day life.

The narrator’s “journeying soul” ultimately rejects traditional life structures, but finds it’s not a straightforward journey, nor does it have a clear destination. Instead, July rejects the taken-for-granted assumptions that characterise modern life and asks what might happen if we drew the boundaries that were right for ourselves instead of observing those that are imposed on us?

Gretchen Shirm’s most recent book is The Crying Room.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout