Living well in your final decade

Health-adjusted life expectancy tells us how many of our final years we can actually expect to enjoy.

It’s tempting to cruise along, eyeing a life horizon into our 80s and beyond. There’s plenty of time yet for that overseas holiday of a lifetime, or to cut down on our days at work and return to that long-neglected sport or hobby. We can waste that gym membership for a bit longer. We’ve got years, most of us, given the average Australian male lives to 80, and women 84, numbers that only keep rising.

READ: Longer lives may not go swimmingly

We’re happy to buy in to the idea that 60 is the new 50, 70 the new 60 and so on.

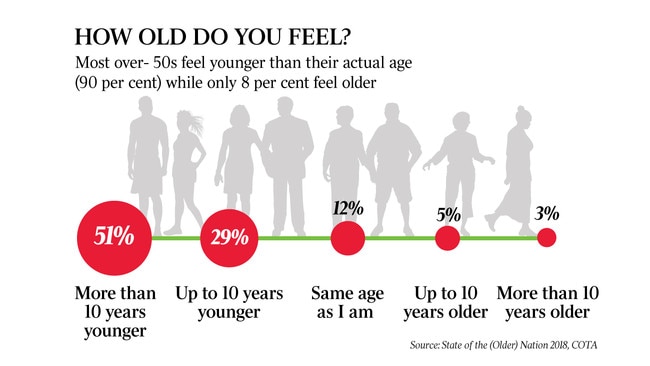

A survey of older people by the Council on the Ageing last year showed 80 per cent of people over 50 felt younger than their actual age, with more than half of over-50s saying they felt more than 10 years younger than they were. And the older we get the greater the gap between our real age and the age we feel. “On average, the over-80s feel 13 years younger than they are, while 50 to 59-year-olds feel nine years younger on average,” the survey finds.

While this is positive, it is looking backwards. It tells us that we feel younger than we are. But what about going forward? Can we be so sanguine? Does that life expectancy in the 80s mean that we continue feeling as we do right now, until we suddenly drop off the twig holing out on the 18th, or looking at the sunset from the roof of our motorhome at Cable Beach?

There is another measure of life expectancy kept by the statisticians around the world. It is called health-adjusted life expectancy, or HALE. It is just as it sounds, the number of years we spend in full health. According to the pre-eminent international study of mortality, the Global Burden of Disease Study, the HALE for Australian men is 69 years and for women 71.7 years.

Suddenly, that horizon for carefree living has moved more than a decade closer. It may have arrived. Of course, these are averages. For some there will be a lifetime of chronic pain while others will get the golden ticket.

What the statistics do show is that there is a fair chance the last decade won’t be all beer and skittles for many of us.

With this realisation comes a new question: How do we live our best last 10 years? Look after your health, starting now.

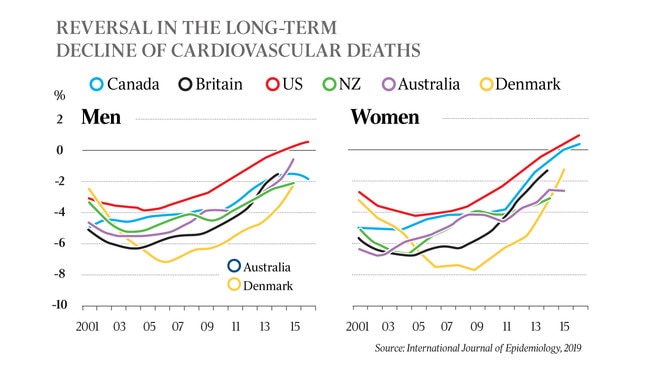

Recent history shows we in Australia have been less successful at looking after ourselves than many other rich countries. After a couple of decades of relatively rapid improvements from 1990 there has been a significant slowdown in life expectancy in Australia in the past 10 years. Our average life expectancy is still growing, but the growth is anaemic.

In global terms, we’ve fallen from having the fifth highest life expectancy in 2009 to the 12th in 2017, the latest available figures in the Global Burden of Disease Study. That ranking is projected to fall even further in coming years, University of Melbourne population expert Tim Adair says our HALE score sits at 14th in the world.

Adair says Australia’s life expectancy rose faster than other developed nations from the 1970s as a result of policy interventions to reduce smoking rates, cutting the prevalence of cancer and respiratory illnesses. “These interventions included increased taxation on tobacco products, advertising restrictions and smoke-free environment legislation,” Adair says. But having banked these life expectancy improvements decades ago, other countries are catching up. “Smoking prevalence in Australia is now relatively low, and there simply isn’t much further for it to fall to have a significant impact on life expectancy.”

That doesn’t mean we’ve done poorly, only that others have done better. However, the bigger influence on the recent life expectancy slowdown is growing levels of obesity, a problem of our own making.

“Australia has one of the highest levels of obesity in the world, with almost one-third of adults and about one-quarter of children obese. It is very likely that obesity is having some impact on slowing life expectancy increases in Australia due to its impact on cardiovascular diseases, and will continue to do so in the future,” Adair says. “Notably, a similar slowdown in life expectancy increases is found in the UK and US, two other countries with very high obesity rates.”

The other point Adair makes is that a disproportionate number of those additional years of life are years of poorer health.

“Since 1990 Australia’s life expectancy has increased 5.5 years; of this increase four years has been in health-adjusted life expectancy,” he says. “This means that more than a quarter of the additional years of life Australians have gained in recent decades arespent in less than full health.”

To live our best last 10 years is to ensure as few of them as possible are in poor health, which requires effort. And we shouldn’t wait until we reach our 70s before deciding it’s time to get healthy. It’s better to start in the 40s, 50s and 60s, though continuing or even starting to do moderate exercise such as walking in your 70s and 80s is critical.

Accountant, mother-of-two and recreational triathlete Pam Tunas, 54, realised something needed to change in her life a decade ago.

“In 2010 I was in a stressful job, working extremely long hours,” Tunas says. “I was 44 at the time and seriously worried I wasn’t going to last to 50. I was 8kg heavier than I was in both my pregnancies. I was struggling to walk up the stairs in my office. I knew I needed to do something.

“I’d been taking my daughters to triathlon training, and the coach had always asked when I was going to come along. When the girls stopped I had all this gear.” Tunas says she found it hard mentally to leave her work, but the exercise gives her that break.

“It switches my mind out of work, and when I come home I’m tired and can easily sleep. I get up fresh the next day,” she says. “I will carry on with this for the next few decades, for sure. I don’t need to be fast, all I need is to be out there every day banking that health benefit for later. I know my body will start depleting one day, but hopefully all this will help me in my rainy days of later life.”

The Council on the Ageing’s national survey of older people last year, State of the (Older) Nation 2018, makes clear the importance of health in the lives of older Australians and the self-assessed benefits of looking after health.

It found poor health was by far the most cited reason for low quality of life, followed by financial issues, stress and loneliness.

On the flip side, health was also the top reason for self-reported high quality of life, followed by family/friend/relationships, general enjoyment of life and good finances.

“People rating their physical health at eight or more out of 10 felt 14 years younger on average, while those rating their physical health poorly at 0-4 felt just two years younger than their actual age,” the survey found.

National Seniors spokesman Ian Henschke agrees on the importance of exercise, saying his members rate health as their biggest worry.

“Do as much exercise as you can and try to increase it as time goes on, not decrease it,” he says. “A wonderful friend of mine was doing an hour a day every morning in his 90s. He was an ex-World War II commando called Rex Lipman and was fond of saying: ‘We are the captains of our souls and the masters of our destiny’. He did one hour of mental exercises every day as well and had friends of every age. He lived a full and fascinating life with no frailty at all at the end.”

Lipman may have been an outlier. The COTA Australia survey found more than half of Australians aged 50-plus don’t do the government-recommended amount of weekly exercise (30 minutes a day for those over 65), with just over a third (36 per cent) doing less than one hour of exercise per week.

COTA Australia chief executive Ian Yates says older people shouldn’t be singled out for not exercising when it is a whole-of-society issue.

“We actually find a big interest in programs for walking, strength training et cetera when they are publicised and offered,” Yates says. “However, often people don’t get the message because there is relatively little preventive health messaging targeting older people apart from a couple of specific matters such as bowel screening.”

Health is only one aspect of life that you can prepare early to live your best last 10 years. Here are the four most important factors.

Find your tribe

Maintaining a sense of community into our final decade is vital to enhancing quality of life. Henschke says there is an epidemic of loneliness and this is an underrated mortality risk. Older people need to actively seek out a community.

“An object at rest tends to remain at rest unless acted on by a force,” he says. “We forget that we are social beings. Around a third of older Australians live alone. We will exercise more if we have friends or a dog that encourages us. Socialising is now being shown to be more important than exercise in quality of life. But if you can do both you’re on a winner.”

Tunas is one such example. Finding a group of like-minded people in the triathlon world has been something she hadn’t expected to be so powerful a force in her life. “The camaraderie is amazing. The support from others in my group when we train, it’s honestly like another family,” she says.

National Ageing Research Institute director Briony Dow agrees on the need to maintain a sense of community, whether that be a family or in a formal care setting.

“We all need to be loved, so having family and friends or kind paid carers to share our lives with is important, so we need to think ahead about this — intergenerational relationships are key,” Dow says.

Appropriate housing

Where you live in your last 10 years can be as important to your quality of life as how you live. Dow acknowledges most older people want to stay in their own homes as long as possible.

“If this is what we want in our old age, we need to ensure that models of both home and residential care enable autonomy and choice, ensure the older person has opportunities to contribute, to retain their independence as well as making sure they are safe and secure,” she says.

“Home care services can only go so far in supporting people at home. My own mother is a good example of this. She got to the point where she had to hang on to something when getting herself dressed and undressed, when preparing meals or even a cup of tea. It is very difficult to complete these tasks independently when living alone in your own home and unless you have a full-time live-in carer, you lose autonomy and choice.”

Dow says NARI’s research shows many aged-care residents find the comfort and safety of communal living a relief from the risk of living independently. “Even if we could substantially increase the amount of care people can get at home, which is sorely needed, we will still need some form of communal living and care to ensure living and dying with dignity.”

Get the financials right

Financial stability is undeniably a critical component of ensuring a good last decade. Longer life expectancies have made financial planning harder and is a topic that creates anxiety for older Australians. COTA’s survey ranks “financial issues” as the second most common reason for poor quality of life.

The Council of the Ageing’s Yates says it is vital to get appropriate health, financial and lifestyle advice, and build that into what you want to achieve, and that this advice applies to people of any age.

Have a sense of purpose

Henschke says the final decade is a time not to turn in but to give of yourself and your time.

“There is a growing body of evidence that having a sense of purpose is vital. For some it’s volunteering, for many it’s caring for someone.

“It may be caring for a friend, a partner, a child, grandchildren or strangers.” he says. “It could be a Landcare group or any community activity to help improve the world we live in. The old saying ‘it is in giving that we receive’ is very true. Many happy long-lived ‘super seniors’ are great givers to the community,”