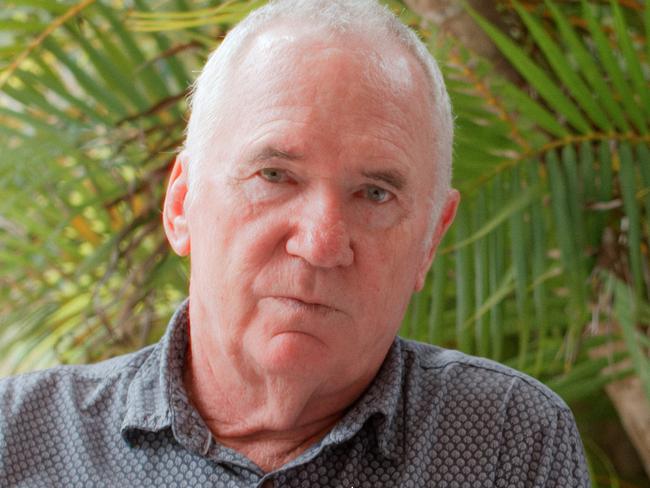

For nine years, Andrew Dyer kept his struggle with Parkinson’s private. Now he wants to speak out

As Andrew Dyer travelled the country dealing with the renewable energy transition, he carried a private struggle. Now he reveals how he juggled his demanding role with a devastating diagnosis.

Andrew Dyer had not long started his new role as Australia’s wind farm commissioner when he noticed something strange during his morning walk to the train station from his home in Melbourne’s southeast.

His left leg dragged as he tried to lift it, and when he inspected his shoes he realised it must have been progressing for some time because the soles on the left shoe were considerably more worn than the right.

That was odd, he thought, as he went about his government-appointed job dealing with issues arising from the growing number of wind farms coming online in Australia.

It was 2016, and Dyer was 53, healthy and busy in the community, serving on the board of the Melbourne Symphony Orchestra alongside various advisory roles at Monash University and with other boards and not-for-profit groups.

About the same time as the dragging foot he noticed excess saliva would build up in his mouth, making it difficult to talk.

Concerned, he went to his GP who carried out an examination and shared the likely diagnosis, a crushing blow delivered to about 50 Australians each day.

It looked like Parkinson’s disease, the neurodegenerative disorder for which there is no cure.

A referral to a neurologist confirmed the GP’s hunch and Dyer and his wife, Theresa, were plunged into a world of medical appointments, medication regimes, physiotherapy and information overload as they digested the news of this progressive condition which most commonly affects movement, speech, swallowing and cognition.

It was a terrible shock but anyone who has met Dyer, an engineer with a long history in governance and industry, would know of his pragmatic and straightforward approach.

“I just thought, well I can sit here and say woe is me, or I can get on and get things done,’’ Dyer said.

He continued as wind farm commissioner until 2021, when the role evolved into the national energy infrastructure commissioner, a demanding job dealing with government, scientists, industry and landholders to resolve community issues arising from the energy transition.

Few people in Dyer’s orbit would have noticed the soft black leather drug bag that accompanied him on frequent country trips just as few were aware of the challenges he faced every day.

Free from the tremors that trouble some sufferers, his condition was not obvious to the untrained eye and he kept it private. Close friends were informed but he didn’t feel the need to share it more widely – until now.

Why now?

“It is becoming more noticeable – ironically not from the disease but the cocktail of drugs required to replace and sustain the dopamine.” (Parkinson’s is caused by a loss of dopamine, a neurotransmitter needed for movement and other functions.)

“I’ve started to exhibit more of the involuntary movement and excessive perspiration from the drugs, so I thought it was time to let people know I’ve got this condition.

“I’m alive and can still get things done but I’ve got challenges.”

According to Parkinson’s Australia, the disorder – the second-most common neurological disease in the country after dementia – affects 150,000 people, occurs slightly more often in males, and has multiple triggers, including age, family history and environmental factors.

Several famous people have spoken out about their diagnosis, including the actor Michael J. Fox, comedian Billy Connolly, rock star Ozzy Osbourne and Australian cricket legend Allan Border.

Their stories help shine a light on the condition but people with Parkinson’s present differently, Dyer said, and in his case symptoms come and go – for example his left leg doesn’t drag anymore.

“It’s a funny old disease; you can line up 10 people who all have the same root cause, that is loss of dopamine, but they all have different outcomes.”

One of the biggest challenges for Dyer, 62, has been managing the medications, a blessing in helping to improve function, and a curse due to the side-effects when they wear off.

During this interview he was at the end of a dose, which lasts about four hours, and his speech had grown slightly slurred.

“I’ll be a bit strange to talk to,’’ he warned. “You don’t produce the words quite as well as you do when you’re on the drugs.”

Nevertheless, his recall and regard for detail were as strong as ever.

Dyer said he managed to work full-time and hold other roles thanks to medication, exercise, physio and the support of his wife, but he had to closely manage his days.

“As commissioner, every day was different and each day would require meticulous planning about precisely when to take various drugs and when and what to eat so that I could be ‘on’ when I needed to be,” he said.

Best laid plans were torpedoed when last-minute changes or delays occurred, especially in Senate Estimates when he risked facing a blaze of questions while the drugs were wearing off, leaving him feeling nauseous and generally unwell.

“Life is not over when you receive a Parkinson’s diagnosis but it does sharpen the focus to get the best out of your days.”

“Managed well, Parkinson’s should not affect your ability to work and participate in life,” Dyer said. “But there will be times where it takes longer for the drugs to kick-in – or they wear off sooner than expected – which can be awkward. Your speech may become slurred and your muscle movement restricted. You just have to deal with it as best you can.”

He delivered his well-received review into community engagement in renewable energy to the federal government in December 2023, and announced his retirement three months later.

What role did his Parkinson’s have in his retirement?

It wasn’t the only factor. “But I felt I needed to retreat a little bit and get on top of the physio and speech work,’’ he said.

Dyer continues to sit on a number of boards and provide consultancy services, and he stays active: he just did a three-week cycling holiday in South Australia which followed a month in Italy last spring.

He recently did more research on his drug options and found a controlled-release option that gives him five to six hours of “on’’ time with less negative effects when the dosage wanes, a significant improvement.

His advice to others staring down the disease? Find a good GP and neurologist who understand the demands of your daily life, but do your own research into medicines and developments as well. Exercise regularly to deal with muscle rigidity.

“And I think it’s important to have a strong purpose in life,” he said.

“Life is not over when you receive a Parkinson’s diagnosis but it does sharpen the focus to get the best out of your days.”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout