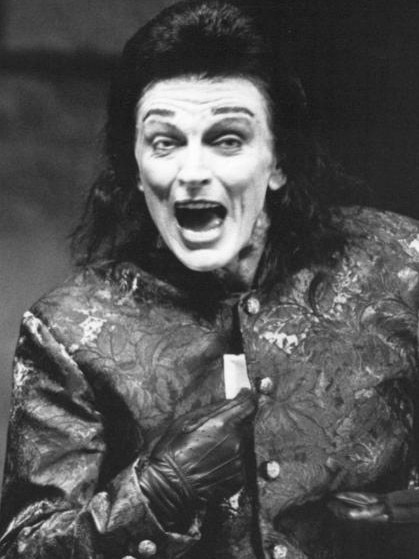

I have Parkinson’s but it hasn’t ruined my life: actor Anna Volska

Diagnosed with an incurable disease, Anna Volska was warned to prepare for a bleak future. What happened next surprised her.

It began quietly and sporadically, and for a time Anna Volska was not overly concerned about the tremor that would appear intermittently in her left hand. “It wasn’t a violent shake. It was just a little tremor and then it would stop,” recalls the Sydney-based actor.

In her early 70s, she contacted her GP and soon after she was sitting opposite a medical specialist, whose diagnosis was clear, if unexpected. “It was a big shock. She said, ‘Definitely it’s Parkinson’s’,” Ms Volska recalls of that momentous day, and the follow-up advice from that same practitioner: she could expect a five-year honeymoon before her symptoms deteriorated.

Parkinson’s disease is a movement disorder of the nervous system that worsens over time. Its range of symptoms includes tremors, muscle rigidity, speech changes and a loss of automatic movements from blinking to smiling. The world’s fastest growing neurological condition, 14,000 Australians are diagnosed with the incurable disease each year.

Shaky and resigned in her doctor’s office that day, Anna Volska faced a future that was as unclear as her diagnosis: “I didn’t know what that would entail, what it would mean.” She was grateful, however, to be receiving the news at 72. “Because I knew it was incurable, because I knew it was progressive, being the age I was, I am not going to have it for long.”

And now here she is, perched on the sofa in her sunny Sydney living room and marvelling, again, at her luck. “It’s been seven years and I’ve been expecting something horrible to happen. And so far it hasn’t,” she says with a smile.

What’s her secret? A positive attitude? Her specific response to the disease? Or the trial that she joined in 2022, in which she was prescribed one of several already licensed drugs to see if it positively impacted her condition?

“Parkinson’s is a bit like a box of chocolates. Some are soft centres and some are tough nuts,” says Professor Simon Lewis, of the progress in different patients of a disease that he describes as a life sentence rather than a death sentence. “Here we see someone doing well because that’s the mystery about their Parkinson’s.”

Where Ms Volska remains comparatively robust, “some of our patients by seven years will not be so independent”, says Professor Lewis, clinical lead of the ongoing trial, in which Ms Volska has participated, for the Australian Parkinson’s Mission. A seven-year clinical trial program, led by the Garvan Institute, Macquarie University and the University of Sydney, the APM is using repurposed drugs to potentially slow and stop the progression of Parkinson’s disease.

At this point post-diagnosis, many other people will have problems with memory and balance. Still, Professor Lewis offers the same advice to all at the outset. “(One) thing we encourage people to do is to be very active and not be a victim of their disease and to fight back. From day one we say you need to be invested in your health.”

That can include regular exercise and speech therapy. “It’s a game of inches. Every inch you gain adds up to yards.” Mindset can also be a factor. “You don’t get to choose what disease you have. You get to choose how you respond to it,” says Professor Lewis. “We know that people who are very positive about their disease do well, and this lady has got that in spades.”

After a lot of apprehension and the worry of that looming five-year deadline – “I wondered if I would wake up the next morning and not be able to walk” – today at 79 Ms Volska is, by her own assessment, living a life that is remarkably similar to her pre-diagnosis days. Her speech is intact, her movements are fine and her tremors are controlled by the three medications she takes daily.

That she is now speaking publicly about her diagnosis attests to her good fortune, but even more to the importance she feels about bringing an often dark topic into the light.

When she chatted to a specialist about being interviewed about her Parkinson’s diagnosis, “he said, ‘I could quite understand if you don’t want to be public about it.’ And I wondered about that. I wondered how many other illnesses are kept private that might make people avoid talking about it,” she says, adding: “I have no trouble talking about it because I think secrecy is destructive and things that aren’t talked about become frightening.”

So she’s happy to discuss her diagnosis and its consequences, which thus far have been minimal and for which she even apologises, given the difficult stories of many others, that she has little that is negative to say. “I guess it’s frightening because the progression is unknown and you really don’t know how it’s going to affect you.”

Was there a period of mourning? “I guess I might have been in denial a bit, because I was put on drugs very quickly.” And those daily medications seem to have controlled the initial tremors, which can otherwise impose their own extra layer of misery.

“It’s such a strange thing,” she says. “It seems to turn people into strange movers, strange creatures. It seems to take your humanity away, your control. Maybe that’s why people don’t like to talk about it.”

In the years since her diagnosis her quality of life, she says, has not changed. She still drives to the holiday home she owns with her thespian husband John Bell. She has just lived through a renovation of their Sydney base and she is in the process of decluttering and culling a long partnership’s worth of books. She’s also still doing some work, and attributes age, rather than Parkinson’s, to the difficulty she recently faced recalling her lines.

Regular checks with her specialist monitor her walking and her movements, and she attends weekly exercise classes that focus on amplitude and balance, an undertaking that she finds exhausting and exhilarating.

Most poignantly, as her daughter Hilary Bell points out, all these years on Ms Volska is still her family’s collective memory-holder and their word champion. “Most of the time,” Ms Bell says to her mother, “I don’t remember you have it.”

The quality of Ms Volska’s life is not what you’d expect when you set out to interview someone who has been living with Parkinson’s for so long. “I’m just enjoying the present,” she says as she glances around her newly renovated home, in which she can one day easily live on a single level. “I’ve got my daughters, one’s here cleaning out the attic, John has taken the dog for a walk and we’re still together. And I can walk. What else can I ask for?”

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout