Scolyer and me: we both beat the odds (so far) on brain tumours

Australians of the Year Richard Scolyer and Georgina Long have caused a huge ripple of hope to run through the pool of brain cancer patients and their families. The Australian’s Tansy Harcourt, who has outlived her own early prognosis, details the effect.

My phone lit up the night world-renowned melanoma pathologist Richard Scolyer revealed the devastating news he had been diagnosed with a malignant brain tumour and unveiled his revolutionary plans to try to beat the unbeatable.

Even my mother – who is well attuned, in the 13 years since my own brain tumour diagnosis, to ignoring misleading “cancer breakthrough”-style headlines – was excited after hearing about Professor Scolyer’s treatment on television.

His is a voice on cancer that people should, and do, listen to.

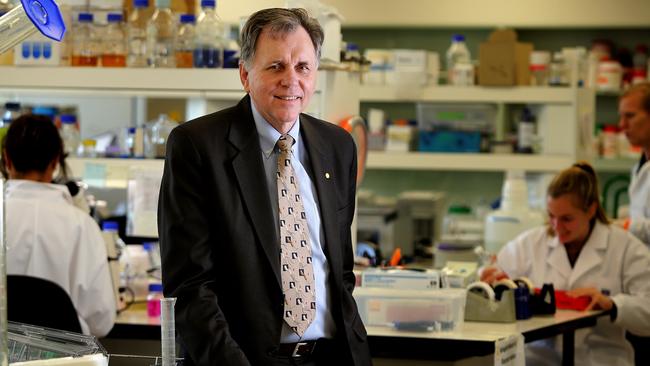

Scolyer is a bit of a rock star in the oncology world, being part of the team that has found a cure for half of previously untreatable advanced melanoma cancers.

Scolyer and colleague Professor Georgina Long are co-medical directors of Melanoma Institute Australia and were recognised for their groundbreaking immunotherapy research by being named as the 2024 Australians of the Year.

Faced with his own terminal diagnosis 15 months ago, Scolyer and Long decided to tackle his brain cancer using the immunotherapy tools he and Long had helped to create for dealing with melanoma. Immunotherapy uses the body’s immune system to attack cancer cells.

Scolyer became Long’s medical guinea pig and is documenting every stage of his treatments and scans on social media.

Next #brain #MRI scan: Friday 27th September 2024 (>16 months post #GBM coming to light in #Poland in May 2023).

— Professor Richard Scolyer AO (@ProfRScolyerMIA) September 25, 2024

MRI looking for:

1. #glioblastoma recurrence

2. #aneurysm stability

3. Treatment effects

How am I travelling/feeling: ok but more anxious this week (scanxiety… pic.twitter.com/9WxC3JZ1se

There is deep respect for the 57-year-old and what he’s helped to achieve in treating cancer, and genuine hope that his and Long’s methods will work for brain cancers too. There is hope that people with glioblastomas (GBMs) might live.

But (and isn’t there always a but?) Scolyer’s incredibly powerful media messaging is also having powerful unintended consequences.

Behind the scenes, the medical community is treading very carefully with how to approach the “Scolyer Effect”.

“This is nothing short of miraculous,” one poster commented after Scolyer announced to his 60,300 Instagram followers in October that his latest scan was stable, although one area of the scan showed enhancement, which can indicate either inflammation from radiotherapy or active tumour. “So many will be helped because of you and your team,” someone wrote.

“Hope the therapy will be available globally soon,” wrote another.

It’s hard not to be warmed by the messages of support. And as a brain-cancer patient myself, I certainly want the heat dialled up on finding a cure.

Survival time

Professor Scolyer’s case is, of course, very different to mine. His tumour is the nastier and faster-acting glioblastoma.

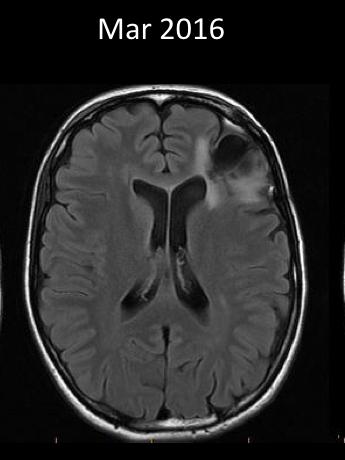

I had just turned 36 when I was diagnosed with a malignant oligoastrocytoma brain tumour 13 years ago. I have outlived my initial forecast end by seven years and counting.

My diagnosis was a complete shock. I was on maternity leave from my job as a newspaper columnist, with a one-month-old baby and a 2.5-year-old toddler, in seemingly perfectly good health.

One minute I was sitting in my bedroom looking lovingly at my daughter as she began her night-time feed, and the next thing I remember is several hours later in a busy hospital ER ward, confused and alone with painfully engorged breasts and a neurosurgery registrar telling me they had found something on my brain.

Like Scolyer’s, my tumour presented through a grand mal (tonic-clonic) seizure. I endured my first brain surgery, part of the tumour was then whisked off to the US for analysis, and a few weeks later I was advised the average survival time was six years.

“Would my daughter be better off not getting to know me?” was one of my first thoughts upon hearing brain tumour treatments at the time could only prolong rather than save lives.

Now it seems Scolyer has opened the door, just a little, to a new way of tackling the condition. Through that door has flooded the desperate hope of many.

‘On a winner’

“Unfortunately, Richard has gone so public with this it has caused great angst among the brain cancer population, friends and carers,” says Helen Wheeler, head of department, Neuro-Oncology at North Sydney Cancer Centre, where Scolyer is partly being treated.

“So far, all our immune glioma trials have failed, but many reading his social media adopt the opinion that Richard is on a winner, and it should be available to all,” says Dr Wheeler.

But there is also little evidence at this stage that his treatment protocol will work.

Brain tumour oncologists can’t offer it to others, and even his beloved Melanoma Institute Australia has had to post a statement on its website saying it does not deal with brain cancer, after receiving more than 100 inquiries.

“We decided to put the message on our website to support brain cancer patients during this difficult time, and to ensure they knew to continue consulting their treating medical teams,” says the chief executive of the Melanoma Institute Australia, Matthew Browne.

“We also wanted to provide an update regarding (our) research paper being out for peer review, and our support for the brain cancer sector’s development of a clinical trial.”

That paper, by Melanoma Institute Australia, is on the treatment given to Scolyer for his GBM. Long told the National Press Club last year that information generated by experimenting on Scolyer rather than first going through animal trials (mouse not guinea pig) had shaved years off the timeline for starting to test drug efficacy.

“We have generated in 10 weeks discoveries that would normally take many years,” Long told journalists.

The problem is that for all of Scolyer’s and Long’s genius, they are not experts on brain tumours, not enough time has passed, and they don’t yet have another guinea pig (or preferably a muddle of guinea pigs) to compare him to.

Neither Long nor Scolyer was available for an interview for this story.

In his recently published book, Brainstorm, Scolyer says Long needs him “to survive for two years to feel like it has had the desired effect. But even if I’m around then, nothing will have been proven. Every now and then in melanoma, a patient is cured for no apparent reason. I could be in that fluky category for brain cancer,” Scolyer writes.

I am one who so far (fingers crossed) falls into that fluky camp.

Trials still to be confirmed

Scolyer’s personalised off-label treatment plan is not available for anyone else. That’s even though so many people, without any other hope, desperately want to try it.

Wheeler, who was part of the clinical trial team that got the drug Avastin (Bevacizumab) to be made available to prolong the quality of life for GBM patients more than a decade ago, says work is under way for a trial based on the approach Long has taken on her colleague and dear friend.

“It’s taken 12 months to try and get the design and support (not all there at the moment) to get a trial up and running that will hopefully answer the question: Is this a great new therapy for glioblastoma, or n=1,” says Wheeler, meaning any result could be a one-off.

Scolyer’s treatment has involved a couple of firsts for brain tumours: immunotherapy is being tried first-up, before the standard courses of chemotherapy and radiotherapy have failed. And Scoyler was treated with immunotherapy drugs before (12 days in his case) the surgery to “debulk” or remove much of the tumour in what’s called neoadjuvant therapy.

In clinical brain tumour trials to date, immunotherapy drugs have been administered after brain surgery.

He then completed several rounds of radiotherapy while remaining on a personalised combination immunotherapy program.

“We are all hoping Richard does extremely well,” says Wheeler. “We don’t really know if he would have done well without all the extra treatment. He is very brave, and lucky he did not get bad side effects.”

Those side effects, which Wheeler says have impacted more than 60 per cent of patients on immunotherapy trials, can include swelling of the brain or the tumour – both of which can cause potentially fatal intracranial pressure, or liver failure.

However, it’s not surprising that Scolyer was happy to take those risks.

Death knell

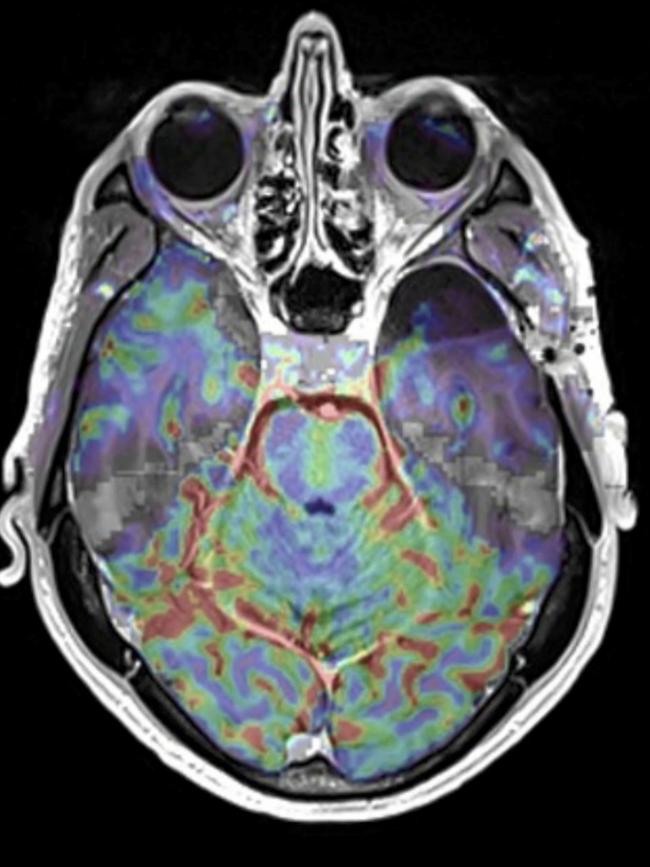

GBM is currently incurable. The brain has a complicated and not fully understood microenvironment. The way tumours metabolise with brain tissue appears to trigger a resistance to chemotherapy treatments, and high-dose radiation therapy can only be administered to the large areas of tumour – rather than the small microtentacles that seem to travel down nerves – because of the damage it can cause to normal brain tissue.

Every brain surgery to “debulk” a tumour comes with the risk of cutting out important brain functionality or a stroke, and some tumours infiltrate too deeply within the brain to reach at all.

Current immunotherapy trials have not yet been successful and are not suitable for Scolyer, who wanted the drug treatment pre-surgery, rather than post. GBM patients usually require surgery quickly to relieve growing pressure on their brains.

According to research published last year by CONCORD, the program for worldwide surveillance of trends in cancer survival, the age-standardised five-year survival period for GBM was “generally poor”, for patients diagnosed between 2010 and 2014.

In Australia, according to CONCORD-3, more than 20 per cent of those patients were still alive after two years but only about 12 per cent remained alive after five years.

What that means is that it is still too early to tell whether Scolyer’s course of attack is working.

It’s worth noting here that Scolyer isn’t shunning existing standard treatments, he is just juggling the order and running them in conjunction with his personalised immunotherapy.

Director of radiation oncology at Northern Sydney Cancer Centre Michael Back admits “few patients are long-term survivors” of GBMs.

“The aim of therapy is generally to delay the tumour from returning and keeping the patient managing well with good function,” says Back, who is one of Scolyer’s specialists (and mine too). “Thus we talk of the median or average survival rather than cure.”

The doctor admits it’s “quite often” that his patients’ carers ask about Scolyer’s therapy and the relevance to their planned treatment.

“The family members are often the ones who are actively searching for answers or fielding messages from friends and other relatives,” says Back. “Generally, people respond positively that there is awareness and research being raised on brain tumours; once explained, they understand that it is not established therapy and not currently available.”

Scolyer writes in his book that Long is working with research organisations in Melbourne and the US (not where he is based in Sydney) and a pharmaceutical company to set up a clinical trial.

“Feedback from the neuro-oncology community indicates we’ve given them hope for a new brain cancer treatment, even if there are risks associated with it,” Scolyer writes.

Where is hope?

One of the problems – apart from death – with brain cancers is that research and treatment are underfunded compared with many other cancers.

The American Cancer Society says there are $US121m ($185m) in breast cancer grants active at the moment, while brain cancers come in at 11th in terms of dollar funding with $US24m. That’s even with the outgoing US President, Joe Biden, having lost a son, Beau, 46, to a brain tumour in 2015. US politicians John McCain and Ted Kennedy also died from GBM.

Globally, according to the International Cancer Research Partnership, research projects involving brain tumours account for 5.97 per cent of the pie, ranking the cancer behind non-specific, breast, and lung.

To be fair, brain tumours kill fewer people. Estimates suggest that globally about 246,000 people died from brain cancer in 2019, whereas breast cancer killed about 670,000. But for brain cancers – which fall into the category of “rare” – the mortality rate among those diagnosed is dramatically higher.

So will immunotherapy hold the best hope for brain tumours?

Lung cancer patients are certainly surviving longer because of the immunotherapy lessons learned in melanoma, and also from targeted therapies which are directed against different molecular changes in their tumours.

“What medicine has learnt is that there are many different subtypes within a particular group of cancer, and that therapies should be individualised for that subtype,” says Back.

“We are learning that this exists with brain tumours, and within the category of glioblastoma we presume there must be multiple different molecular subtypes that could be individualised for therapy. Unfortunately we currently do not have that knowledge, and need more research to translate the improvements in other cancers to glioblastoma.”

Back says there could be multiple reasons immunotherapy trials for brain tumours haven’t worked yet, including that the molecular structure may not be favourable to creating the immune response – which means it just doesn’t work – or that an immune response such as swelling can be deadly within the brain environment.

“So we may need to design alternative research to give the immune therapy in a different format to other tumours, rather than just copying what has worked well in melanoma or lung cancer,” says Back.

As one of his doctors, Back cannot comment specifically on Scolyer’s treatment.

To date, the best indicator of living longer with a malignant brain tumour has been the success of the surgery. Personally, I’ve had two, and others I’ve come across during my brain tumour treatment have had three or four.

Some tumours are too deep in the brain to access, and too hard to distinguish from normal brain tissue. Surgeons even resort to burning what they believe might be the perimeter of a tumour with the electrical currents of a diathermy machine, to see if it bubbles differently from brain tissue. A result that might indicate they have found an edge.

Scolyer has had what is called a “successful resection”, meaning his surgeon at the Royal Prince Alfred in Sydney’s Camperdown managed to remove the bulk of the visible tumour and left him with no obvious neurological defects.

The professor has told his Instagram followers he has been suffering from epileptic fits, which was how he came to be diagnosed in the first place, but it is unclear whether the seizures are from the tumour, the brain surgery or the result of any of his treatments.

Test case

If his treatments work, Scolyer won’t be the first Australian medic to successfully use himself as a test. Barry Marshall infected himself in 1985 with Helicobacter Pylori to prove that stomach ulcers are infective in nature and went on to win the Nobel prize for his work.

Australian Medical Association federal president Danielle McMullen says that what Scolyer is having done to himself, in tandem with Long’s advice, may provide a “groundbreaking” advance in treatment options but it’s not yet “ethical” to test on GBM patients.

“He was the experiment,” says Dr McMullen, who is a general practitioner. “It’s unethical for us to do that on the general public. We need to make sure that things go through really strict safety protocols, because everyone deserves the best possible treatment. We can’t just skip the steps.”

What McMullen says makes perfect sense, but might still be hard for someone with a terminal diagnosis to swallow.

I certainly recognise the feeling of wanting to throw absolutely everything at the problem. The AMA chief understands this too. Her own father died from melanoma 15 years ago after being one of the very early trial participants for immunotherapy using the methodology likely created by Scolyer and Long.

“It didn’t work and I have some personal understanding of the ups and downs that people go through when you’re part of a clinical trial and you’re out of other options, and you give it a crack,” McMullen says.

“His experience contributed to a situation where, 15 years later, we’ve now got much better versions of immunotherapy for melanoma in particular, and also a number of other cancers.”

Clinical trials can take years to set up, and then in the case of rare cancers such as brain tumours, need to be opened globally to find enough people with a similar base point to start from.

Then there is the issue of costs.

In Australia, we assume that our treatment will be free. This is not always true. My first surgery cost only the amount my anaesthetist charged because my neurosurgeon didn’t charge over the Medicare rate, but my second surgery with a different neurosurgeon was a mid-five-figure sum. And that’s before you get to the cost of the drugs.

“Treatments such as immune therapy are expensive and thus need to be restricted to cancers where we have evidence that they are effective,” says Back. “A standard immunotherapy drug for melanoma or lung cancer on the PBS will cost Medicare $15,000 to $20,000 a month and will often continue for two years. These drugs will come off patent in the near future but still not until about 2028 will biosimilar drugs start to become available.”

That means if there is no proof that the drugs will work, patients themselves might be forking out $240,000 a year for a possibly ineffective therapy.

Scoyler understands that as patient zero his efforts might not save him but help to save others, telling Australian Story he was “more than happy to be the guinea pig”.

His professional hope is to “blow open the brain cancer field and transform it for all brain cancer patients”, he told the ABC program. Not that he is just being altruistic. I “might live longer and there’s a small chance I could be cured”, he said.

Keeping it real

It’s clear that Scolyer is trying in public to balance recognition as a cancer expert that his treatment might not work, with his own hope as a person that it will. Every week it feels like there are headlines proclaiming the latest cure for cancer, and McMullen says that these stories can affect patients quite differently.

“Some of the celebrity stories about hope are more helpful than others,” McMullen says. “I think Richard has tried to be fairly circumspect and be clear about the fact that his treatment was experimental, and that while it brings hope, it’s a long time away.”

Other stories, she says, can be quite misleading.

“Every week, there’s some fancy new treatment that’s out, and patients do sometimes come in and ask about it, and then you have to have the conversation of, yes, this is looking maybe promising, but it’s at least 10 years away and people take that in a variety of different ways.”

A greater understanding of the genetic breakdown of brain tumours is also helping, at least in the diagnostic stages.

My own tumour has a mutation of the IDH1 gene. This fact wasn’t noteworthy back when I was diagnosed in 2011, but scientists now know it means I have a better prognosis for survival time than first thought, my tumour is now categorised differently to the initial oligoastrocytoma definition, and the IDH1 gene is the focus of a number of so-far unsuccessful clinical trials of drugs for a cure. Fingers crossed one will work.

For me, as someone who likes facts, graphs and statistics, this is something for me to hook my hope on. I read every medical paper I can get my hands on, I pester Back whenever any new trials show promise – so far only one looks vaguely promising but is far too expensive. Sometimes I even manage to get the data on trials before he does, and I come into every one of my six-monthly MRIs a little anxiety sleep-deprived with a bucket full of questions.

I like to think that as one of his longer-living patients Back indulges my need to know.

I am watching closely to see how Scolyer’s treatment works. While his brain tumour has a different name to mine, it shares some characteristics and it stands to reason in my non-medical mind that there must be something in what works for him potentially working for mine too.

At a minimum, any lessons learned about how to avoid a tumour swelling will be useful for any type of brain-tumour immunotherapy. I am grateful to Scolyer for leaning on his medical connections to make himself the guinea pig.

Wheeler says ideally we would all “cool the jets until we can validate a good outcome, define the risks, and be in a position to offer to more patients”.

Scoyler probably doesn’t have that much time. It’s no wonder he is throwing his and Long’s own book at the problem.

It certainly feels like he holds a lot of people’s hope in his hands.

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout