The ‘holy grail’ of heart health: a valve that grows inside you

A device that can infuse itself with human cells is being called a ‘holy grail’ because it ends the need for repeated operations.

Heart valves that grow in the body are to be tested in British cardiac patients in a breakthrough for regenerative medicine.

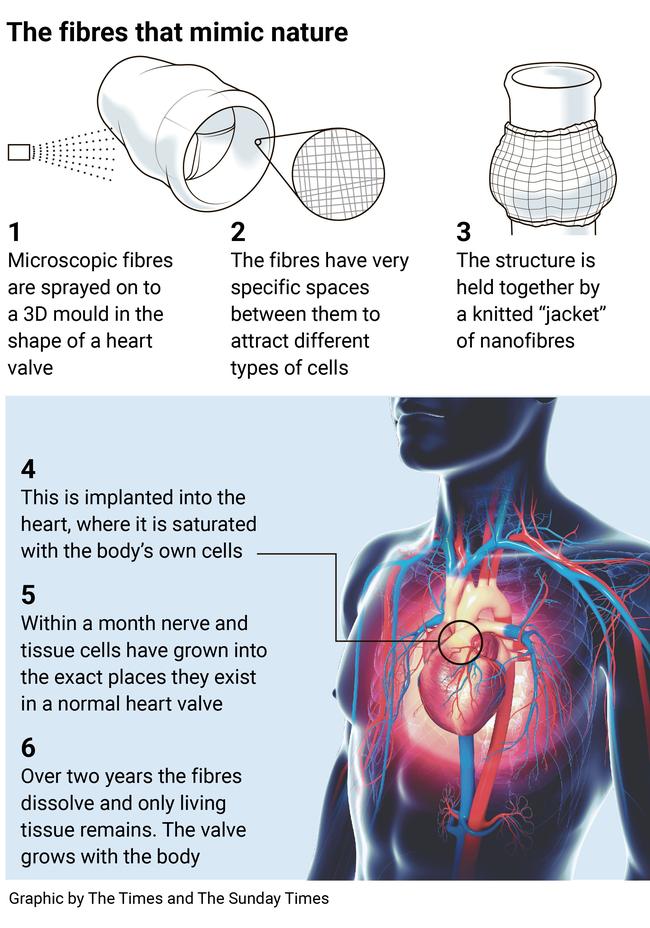

More than 50 initial patients will receive a temporary valve made of microscopic fibres. It acts as a scaffold which, once implanted, becomes infused with the body’s cells. The scaffold dissolves over time, leaving a self-grown living valve made of the patient’s tissue.

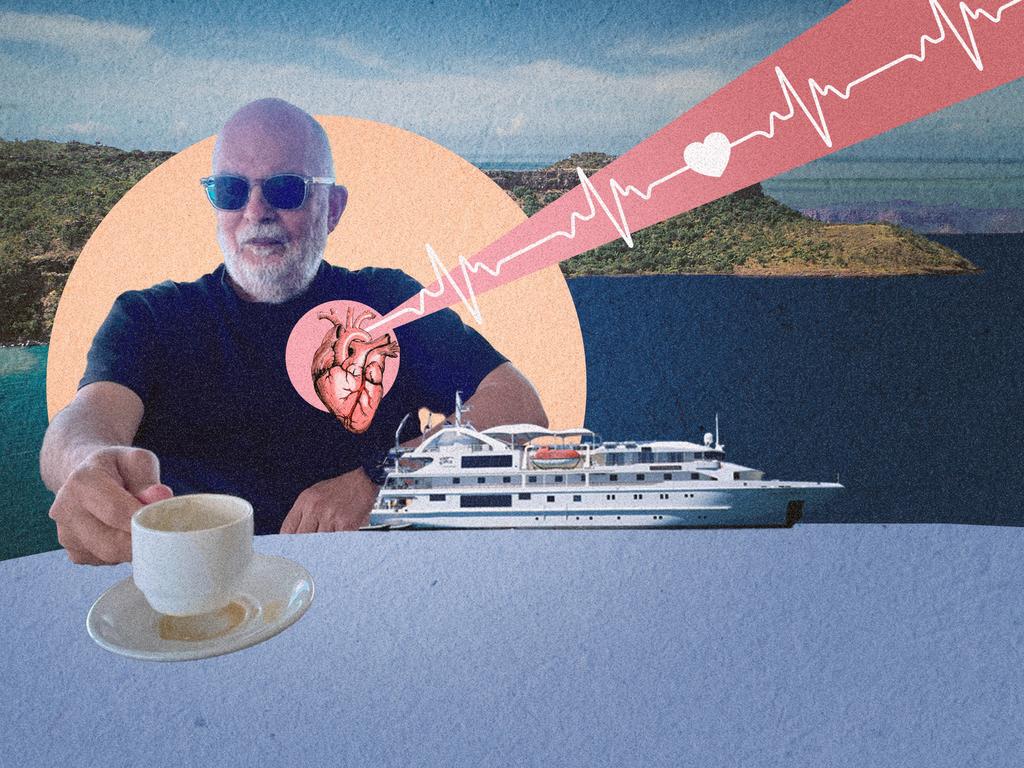

Cardiologists said it would be especially useful for young children with congenital heart defects because the new valve will grow with them. At present artificial valves have to be replaced every few years. The development is being spearheaded by Professor Sir Magdi Yacoub, a pioneering cardiac surgeon who performed Britain’s first heart-lung transplant, at Harefield Hospital in northwest London. He has operated on more than 20,000 patients in a 50-year career.

Now in his eighties and still working at the hospital, he believes this could be his most important contribution to medicine. “Throughout the years I have been working, I have witnessed an epidemic of valve disease, which kills so many people,” he said.

“I have been trying all my life to take experience from the lab to the clinic. This I consider one of the most important things I want to leave behind as a legacy - the biggest present to mankind.”

Scientists have been attempting for years to develop valve replacements engineered from the body’s own tissue.

Today patients are fitted with either artificial valves, meaning they have to take anti-clotting medication for life, or biological ones made of pig, cow or donated human tissue, which usually last ten to 15 years. Both can be rejected by the body.

About 13,000 heart valve replacement operations are performed in England each year and 300,000 worldwide, a number set to rise as heart disease rates climb. By 2050, 850,000 replacements a year are expected globally.

Heart valve problems affect an estimated one in four over-60s, caused by ageing, inflammation and infection. Congenital defects also cause valve conditions, affecting an estimated 8 in 1,000 babies born in the UK.

When valves are diseased, they become stiff and narrow or leaky and ineffective, meaning they either do not open fully or do not close properly when controlling blood flow around the heart. Left untreated, this can result in heart failure, stroke or a heart attack.

Children born with congenital heart valve disease typically need at least five procedures to replace valves before adulthood because artificial valves do not grow with them. Every operation carries a risk of complications, including infection, excessive bleeding, stroke, blood clots and kidney problems.

The living valve could be life-changing for patients because it would eliminate the need for repeat surgery and the risk of rejection. Yacoub said: “I always say nature is the greatest technology. It is so superior to anything we can make. Once something is living - whether that’s a cell, tissue or [the living valve] - it adapts on its own. Biology is like magic.”

To make the valve, scientists spray a cobweb of fine fibres into a 3D replica of a human heart valve, creating a scaffold. This is held together by a knitted mesh “jacket” of fibres that can withstand the pressure of pulsating blood flow. The tiny fibres are made of polycaprolactone, a biodegradable polymer commonly used as a coating for tablets, which slowly breaks down in the body into harmless carbon dioxide and water.

To mimic nature, the fibres are of different widths and have spaces between them that attract cells; this creates an environment where they thrive. After settling into these spaces, cells grow and trigger the development of the cell types needed to make the heart valve work.

A study of the device in sheep, published a year ago in the journal Nature Communications Biology, revealed that within four weeks there were more than 20 types of cell – including nerve and fatty tissue cells – functioning in the places they would be in a natural heart valve.

Although other researchers around the world have tried to create living valves, this project, run by the company Heart Biotech at Harefield Hospital, is the first to have successfully stimulated the growth of nerve cells. Within six months of implantation, the structure is made up of living cells from the patient’s body, and within a year or two it will have dissolved, leaving the patient with a new heart valve grown from their own cells. It will continue to grow with them throughout their lives.

Researchers have received funding from the British and German governments. The first human trials, expected to start in 18 months, will include 50 to 100 patients, including adults with expired heart valve replacements and children who would otherwise face a series of risky operations in a short time.

The trials will test how the device performs compared with an established artificial valve and will be conducted by an international team including doctors based at University College London and Great Ormond Street hospitals, as well as participants in New York, Italy and the Netherlands.

In the first trials, the living valve will be used to replace the pulmonary valve, which controls blood flow to the lungs, as this is under the least pressure. But scientists are confident it will soon be ready for all types of valve replacement.

Dr Sonya Babu-Narayan, associate medical director of the British Heart Foundation, described a tissue-engineered heart valve replacement as “the holy grail” for the surgical treatment for heart valve disease. She said: “It is early days, but if further research shows the approach is successful in humans, many people around the world could live well for longer without the need for repeated heart valve procedures.”

THE SUNDAY TIMES

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout